Warrendale was a center in Canada where emotionally disturbed children were brought to live in groups of 12, each with a trained staff of eight. A note at the beginning of the film emphasizes that these are not brain-damaged or retarded children. They are of normal intelligence, but gravely disturbed.

The treatment at Warrendale was experimental, involving a maximum amount of physical contact as a direct way to express love and reassurance. The children were encouraged to release all their anger and aggression while being tightly held by two or three adult staff members. During these “holding sessions,” they were told they were not responsible for anything they might do. They were being given a safe way to drain off the latent violence that seemed to be associated with their problems.

I am not competent to say whether this treatment was wise or effective, and the film does not make a special argument for it. Instead, King and his crew have acted entirely as observers, using portable, unobtrusive equipment to record some six weeks in the life on Warrendale. Like the best of cinema verite, “Warrendale” would rather show life than judge it.

A structure was given to the film almost accidentally when Warrendale’s cook died unexpectedly. The news is broken to the children in a group meeting. Some of them appear indifferent (“She wasn’t any relative of mine.”) Others react hysterically, and the staff members hold one young girl while she sobs and cries at the top of her voice: “It’s a lie! It’s a lie!” Another of the young patients blames herself, and a staff worker calmly repeats over and over: “It’s not your fault. You didn’t cause Dorothy’s death. It’s not your fault.”

In these scenes of sustained and heartbreaking emotion, we begin to understand the Warrendale experience. The children are victims of the same isolation and loneliness that plagues all men, and their early environments apparently did not provide them with socially approved ways of coping with these feelings. So they began to act strangely in order to call attention to themselves, and perhaps to attract help. Some became delinquents, others self-destructive (one young girl combs her hair violently and painfully, and a staff member says, “You don’t have to hurt yourself. Your hair is beautiful”).

Still other children developed enormous feelings of guilt, blaming themselves for almost anything. These are perhaps the most pathetic, and the Warrendale treatment encouraged them to release their fear and grief. In these scenes we see a human closeness that is often lacking from life, and almost always from the screen. This depth of emotion may embarrass some audiences, but it is the only way to deal honestly with material, of this importance.

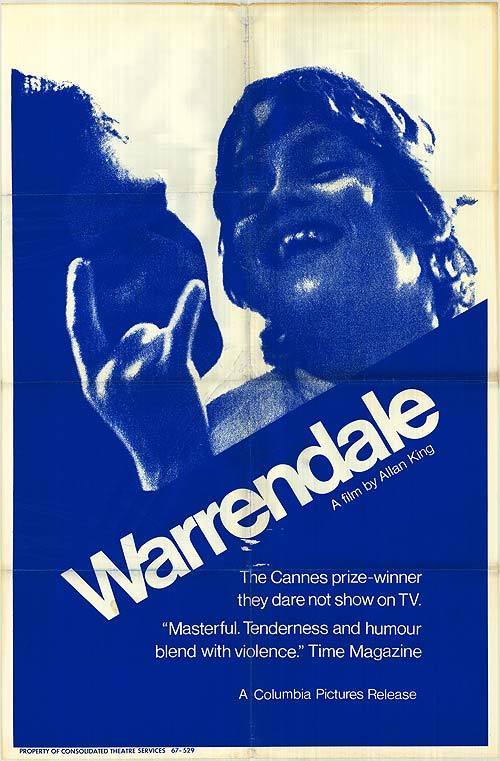

(“Warrendale” shared the 1967 Cannes Festival award with “Blow-Up,” and was named the best documentary of the year by the National Society of Film Critics and the British Film Critics Society.)