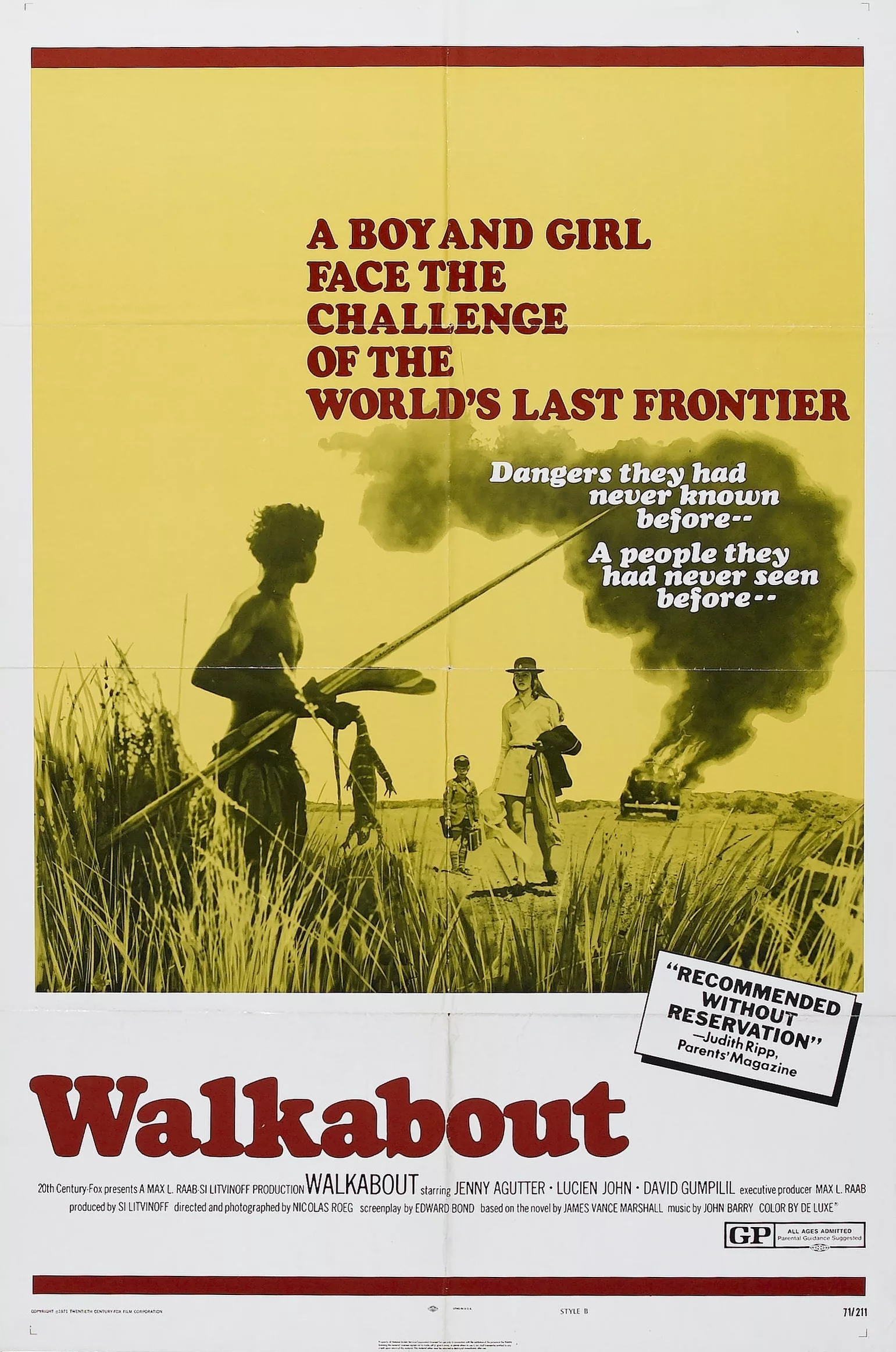

It is possible to consider “Walkabout” entirely as the story it seems to be: The story of a fourteen-year-old girl and her little brother, who are abandoned in the Australian outback and then saved through the natural skills of a young aborigine boy. It is simpler and easier to consider it on that level, too, because “Walkabout” is a superb work of storytelling and its material is effortlessly fascinating. There’s also a tendency (unfortunate, probably) to read “Walkabout” as a catch-all of symbols and metaphors, in which the Noble Savage and his natural life are tested and found superior to civilization and cities.

The movie does, indeed, make this comparison several times. Hundreds of miles from help, the girl turns on her portable radio to hear a philosopher observe: “It is now possible to state that ‘that is’ is.” Well, this isn’t exactly helpful, and so we laugh. And more adolescent viewers may have to stifle a sigh and a tear when the girl is seen, at the movie’s end, married to a cloddish office clerk and nostalgically remembering her idyllic days in the desert.

The contrast between civilization and man’s more natural states is well-drawn in the movie, and will interest serious-minded younger people (just as, at the level of pure story, “Walkabout” will probably fascinate kids). But I don’t think it’s fruitful to draw all the parallels and then piously conclude that we would all be better off far from the city, sipping water from the ground, and spearing kangaroos for lunch.

That sort of comparison doesn’t really get you anywhere and leaves you with a movie that doesn’t tell you more than you already knew. I think there’s more than that to “Walkabout.” And I’m going to have a hard time expressing that additional dimension for you, because it doesn’t quite exist in the universe of words. Even in these days of film experiments, most movies have their centers in the worlds of plots and characters. But “Walkabout”…

Well, to begin with, the film was directed and photographed by Nicolas Roeg, the cinematographer of “Petulia” and many other British films. Roeg’s first stab at direction was as co-director of “Performance.” This was his first work as an individual. I persisted in seeing “Performance” on the level of its perfectly silly plot, and on that level it was a wretched movie indeed. People told me I should forget the plot and simply enjoy the movie itself, but I have a built-in resistance to that notion, usually. Perhaps I should have listened.

Because Roeg’s “Walkabout” is a very rare example of that kind of movie, in which the “civilized” characters and the aborigine exist in a wilderness that isn’t really a wilderness but more of an indefinite place for the story to be told. Roeg’s desert in “Walkabout” is like Beckett’s stage for Waiting for Godot. That is, it’s nowhere in particular, and everywhere.

Roeg’s photography reinforces this notion. He is careful to keep us at a distance from the physical sufferings of his characters. To be sure, they have blisters and parched lips, but he pulls up well short of the usual clichés of suffering in the desert. And his cinematography (and John Barry’s otherworldly music) make the desert seem a mystical place, a place for visions. So that the whole film becomes mystical, a dream, and the suicides which frame it set the boundaries of reality.

Within them, what happens between the boy and the girl, and the boy and the little brother, is not merely “communication” or “survival” or “cooperation,” but the same kind of life-enhancement that you imagine people feel when they go into the woods and eat berries and bring the full focus of their intelligence to bear on the problem of coexisting with nature.