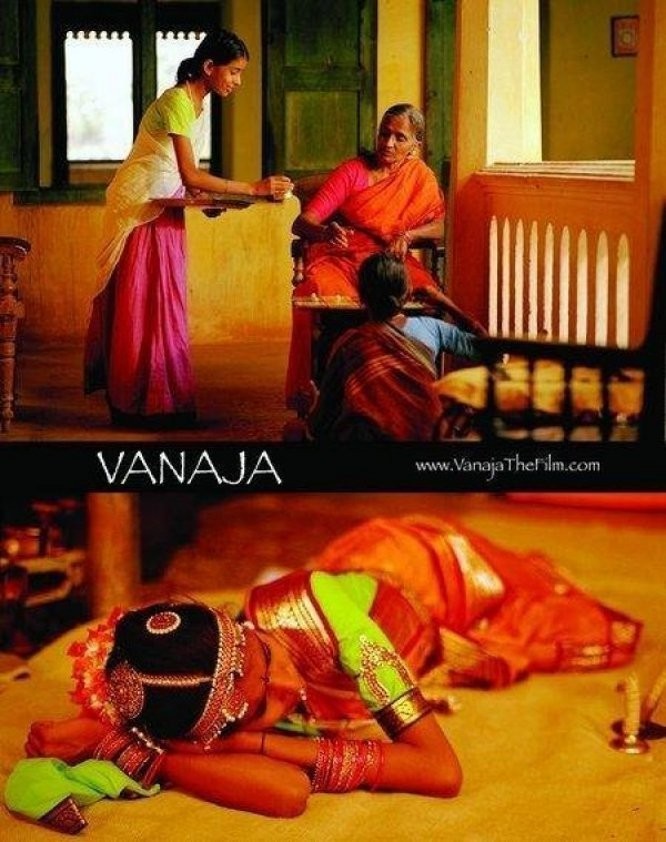

‘Vanaja,” a beautiful and heart-touching film from India, represents a miracle of casting. Every role, including the challenging central role of a low-caste 14-year-old girl, is cast perfectly and played flawlessly, so that it is a continuing pleasure to see these faces on the screen. Then we learn their stories. The actors, naturally and effortlessly true, are all nonprofessionals who were cast for their looks and presence, and then trained in an acting workshop set up by the director, Rajnesh Domalpalli. He recalls that his luminous star, Mamatha Bhukya, an eighth-grader, was untrained, and had to learn to act and perform classical Indian dances during a year of lessons set up in his family’s basement!

But this movie is not wonderful because of where the actors started. It is wonderful because of where they arrived, and who they became. Bhukya is a natural star, her eyes and smile illuminating a face of freshness and delight. And the other characters are equally persuasive, especially Urmila Dammannagari, as the district landlady, who has to negotiate a way between her affection for the girl and her love for her son.

But why are you reading this far? An Indian film? Starring Mamatha Bhukya and Urmila Dammannagari? Lesser readers would already have tuned out, but you are curious. And so I can promise you that here is a very special film. It was made by the director as part of his master’s thesis in the film department at Columbia University, shot over a period of years on a $20,000 budget, and all I can say is $20,000 buys a lot in India, including a great-looking, extraordinary film.

Let me tell you a little of the story. In a rural district of South India, a 14-year-old girl named Vanaja (Bhukya) lives with her shambling, alcoholic father. Life is bearable because she makes her own way, and when we first see her, she’s in the front row of a dance performance with her best friend, Lacchi, where they’re giggling like bobby-soxers (a word that will mystify some of my Indian readers, but fair’s fair). What beautiful girls they are, and I mean that not in a carnal but a spiritual sense. The sun shines from their skin.

Vanaja’s father takes her to the local landlady, Rama Devi (Dammannagari) and asks for a job for her. Rama Devi, in her late 40s, is not a stereotyped cruel landowner, but a strong yet warm woman with a sense of humor, who likes the girl’s pluck during their interview, and hires her — at first to work with the livestock. But Vanaja dreams of becoming a dancer and persuades Rama Devi to give her lessons.

As we know from Satyajit Ray’s “The Music Room,” many rural landowners pride themselves on their patronage of the arts; to possess an accomplished dancer in her household would be an adornment for Rama Devi. The lessons go well, and there are dance scenes that show how much the actress learned during her year of basement lessons, but there are no Bollywood-type musical scenes here; indeed, the film industry of this district not far from Hyderabad is known as Tollywood, after the Telugu language. It is also a status symbol to speak English, which Vanaja has never been very good at.

The landlady’s 23-year-old son, Shekhar (Karan Singh), returns from study in America, prepares to run for office and notices the new beauty on his mother’s staff. Though you may guess what happens next, I won’t tell you, except to observe something that struck me. Although there is usually no nudity or even kissing in Indian films (and there is none here), the screenplay is unusually frank in dealing with the realities of sexual life.

Vanaja becomes 15, then 16. She grows taller. She will be a great beauty. But her lower-caste origins disqualify her for marriage into Rama Devi’s family, her drunken father is a worry and burden, the local post-boy is fresh with her, and although the landlady is very fond of her and covets her dancing, her son will always come first. Vanaja’s only real allies are her childhood friend and Radhamma, the landlady’s cook and faithful servant.

In any Indian film, many of the pleasures are tactile. There are the glorious colors of saris and room decorations, the dazzle of dance costumes and the dusty landscape that somehow becomes a watercolor by Edward Lear, with its hills and vistas, its oxen and elephants, its houses that seem part of the land. In this setting, Domalpalli tells his story with tender precision, and never an awkward moment.

The plot reminds me of neo-realism crossed with the eccentric characters of Dickens. The poor girl taken into a rich family is also a staple of Victorian fiction. But “Vanaja” lives always in the moment, growing from a simple story into a complex one, providing us with a heroine, yes, but not villains so much as vain, weak people obsessed with their status in society. When the final shot comes, we miss the comfort of a conventional Hollywood ending. But “Vanaja” ends in a very Indian way, trusting to fate and fortune, believing there is a tide in the affairs of men, which — but you know where it leads. Let’s hope it does.

“The Music Room” is included in the Great Movies section of rogerebert.com.