The car itself is the star of this movie, the low-slung, bullet-nose that looks like a discreet cross-breeding of the postwar Studebaker and the Batmobile. And the most amazing fact about the Tucker automobile is that Preston Tucker did actually succeed in building 50 of them, just as he said he would, before he was shot down by the Big Three from Detroit and their hired guns in Washington.

Would automotive history have been different if Tucker had put his dream into mass production? Probably not. The Tucker would probably have thrived for a few late-1940s years and then joined the long, slow parade of the Hudson, the Kaiser, the Nash, the Studebaker, the Packard, the Willys and all the other makes that your dad always warned you couldn’t get parts for.

And yet Francis Ford Coppola’s new film is not so much about the car as about the man, and it is with the man that he fails to deliver.

“Tucker: The Man and His Dream” paints us a Preston Tucker who is a genial, incurably optimistic dreamer, a man who gathers a small band around him and inspires them to build a great car, and yet all the time he lacks an ounce of common sense or any notion of the real odds against him. And since the movie never really deals with that – never really comes to grips with Tucker’s character – it begins as a saga but ends in whimsy.

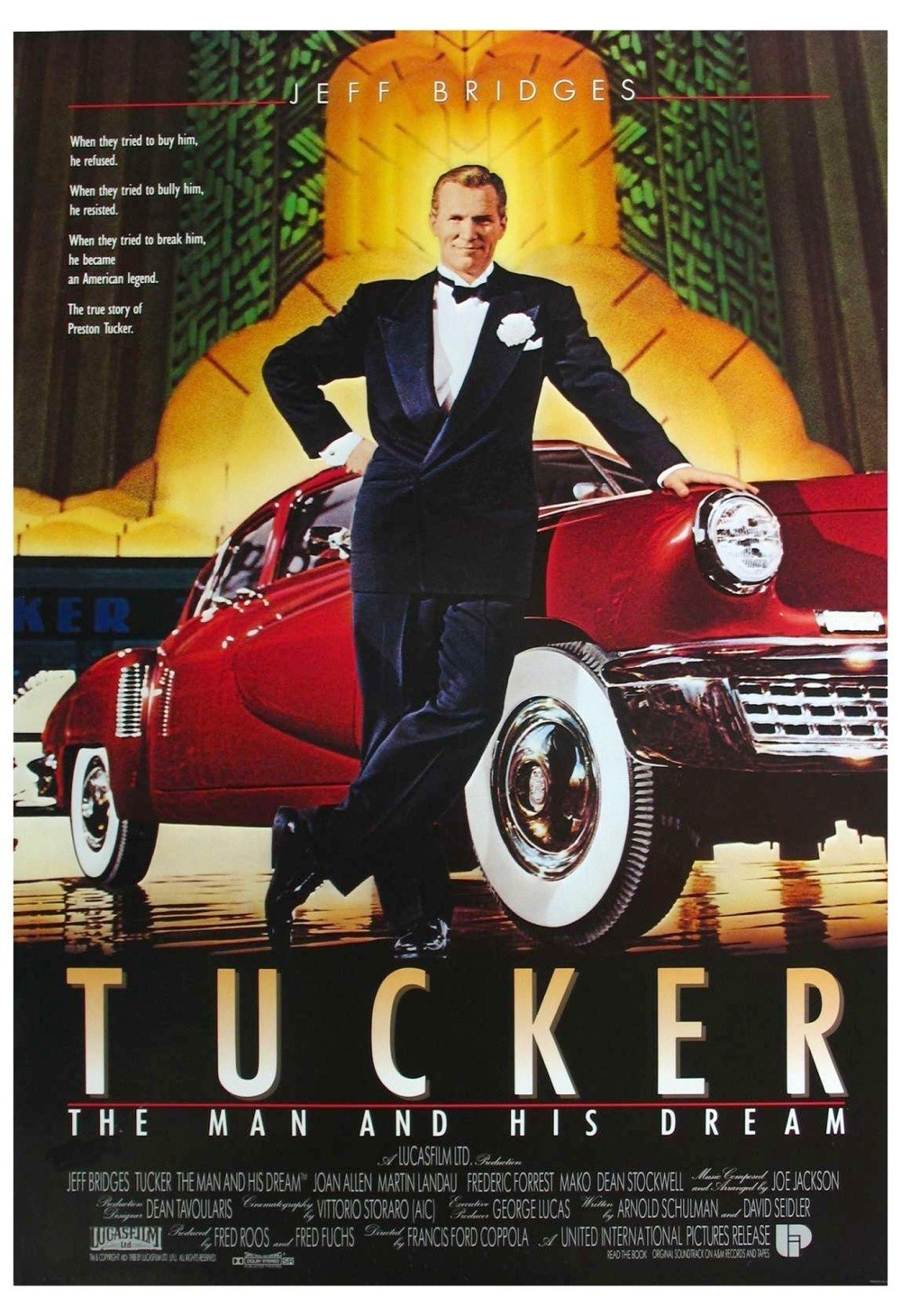

Tucker is played by Jeff Bridges with a big, broad smile and a knack for finding hope even in the ash heaps of his dreams. He lives in the center of a large, cheerful family, with a wife (Joan Allen) and a brood of kids who seem cloned directly from those late-1940s radio sitcoms where somebody was always banging in through the screen door and announcing that he smelled fresh apple pie.

Tucker made his fortune during World War II by inventing and manufacturing the Tucker Turret for Air Corps bombers. Now he thinks the American public is ready for a truly modern automobile – one with great design and good mileage and safety features like pop-out windshields and seat belts. His master touch is a third headlight in the middle of the front grille that will turn in the same direction as the steering wheel. But Detroit doesn’t much like the idea of seat belts – they might give the public the idea that cars aren’t safe – and they don’t like the idea of Tucker, either.

Tucker applies for the use of a war-surplus manufacturing plant on the Southwest Side of Chicago, and gets it. He and his team throw together a prototype automobile out of spare parts scavenged in a junkyard. He’s a master at personal publicity, floats a stock issue to raise money, sets up his assembly line and starts racing against a deadline for introducing his first model.

But it’s about here that the movie really loses its grip. We are never given any real insights into what makes Tucker tick; we see him from the outside, like the public, and he’s all bluff and charm and sideshow pep talks. The problems of the assembly line are also painted without any details. There is no sense here that the movie gives any serious attention to the process.

The worst scene in the movie is the most crucial, the scene where Tucker is scheduled to unveil his new beauty to the assembled American automobile press. We get a passage that’s too long and too confused, a comedy of errors as the workmen try to push the big car up a ramp as a fire starts backstage and Tucker stands in front of the curtain bamboozling the press. A little of this would have made the point; Coppola pushes it to distraction.

It is difficult, by the way, to avoid the notion that, in Preston Tucker, Coppola sees a version of himself. Coppola says he has been fascinated by the Tucker legend ever since he first saw a Tucker car in the late 40s, and he has owned a rare collector’s model during the 10 years he has been trying to get this dream film off the ground.

Many details are the same between the automaker and the filmmaker: the loyal wife, the big family, the close-knit group of friends who pitch in at all hours, the grandiose schemes, the true genius, the peculiar knack of confusing the public with unnecessary explanations and, in particular, the ability to hold a launching – or a premiere – in the worst possible way. Coppola is known for holding “secret” previews that the press somehow gate-crashes, leading to premature and hostile reviews. And he is known for fiascos like his ill-advised decision to publicly announce that he was having “problems” with the ending of “Apocalypse Now,” allowing self-doubt to cast an unnecessary shadow on his masterpiece.

The parallels between Coppola and Tucker are so obvious that it’s surprising Coppola didn’t observe one more: He has been as protective of Tucker’s private life as he rightly is of his own.

“Tucker” does not probe the inner recesses of Preston Tucker, is not curious about what really makes him tick, does not find any weaknesses, and blames his problems, not on his own knack for self-destruction, but on the workings of a conspiracy. And it makes the press into a convenient and hostile villain. This won’t do. If we’re offered a movie named “Tucker: The Man and His Dream,” we leave feeling cheated if we only get the dream.