Québécois filmmaker Xavier Dolan is only 26 years old and has already directed 5 features, 4 of which he wrote. Some he has acted in, some he has not. He has gotten the kind of attention young artists dream about, some good, some bad, festival awards, critical raves and critical derision. As an actor, Dolan has a blank and beautiful quality reminiscent of the young Alain Delon, whose almost otherworldly good looks were show-stopping and yet somehow off-putting as well (utilized to great effect in Jean-Paul Melville’s “Le Samouraï”). Audiences are drawn to such cinematic beauty, but can also be envious, and slightly hostile. (Alfred Hitchcock loved to fill his films with beautiful people and then make horrible things happen to them.) Is there anything there behind that mask of pure beauty?

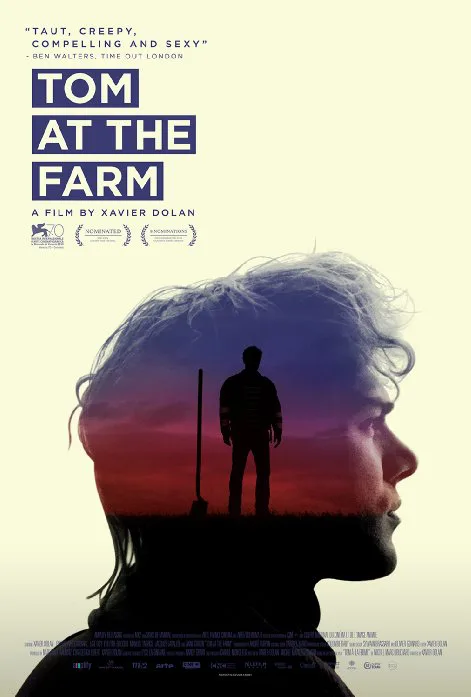

Dolan’s latest, “Tom at the Farm” was completed several years ago (before last year’s “Mommy“) and is the first time he has adapted an extant work for the screen. Based on a play written by Michel Marc Bouchard (and Bouchard wrote the adaptation with Dolan), the adaptation appears to adhere closely to the original (I have not seen the play), with only a couple of scenes where the action is “opened up.” (Those scenes, on the whole, are not successful.) “Tom at the Farm” strains to be a psychological thriller but its length (102 minutes) dissipates the tension that should be taut and compressed. This is Dolan’s first attempt at genre, and while there is much to admire here (mainly the visuals and the score, both stunning), Dolan’s interests lie in the strange undercurrents of sado-masochism between the two main characters, and it’s a through-line that deserves more attention. That through-line could have carried the entire movie if Dolan had let go of being faithful to the original.

Tom (Dolan) drives through serene and brightly-colored autumn fields to attend the funeral of his boyfriend Guillaume. Once he arrives and meets Guillaume’s mother Agathe (Lise Roy, who gives the best performance in the film), he learns that his boyfriend was closeted to his mother and had lied that he had a girlfriend. Tom is a greasy-haired boy, dressed in black leather and huge black boots, clomping through the immaculate farmhouse and the rural surrounding environment, a slash of black against the yellow dying corn. Agathe is eager to meet someone who knew her son, but confused and hurt that the never-met girlfriend did not attend the funeral.

The emotional pressure in that farmhouse is so extreme that Tom is roped into going along with his dead boyfriend’s lie. Tom closets himself, in other words. He decides not to read the shaky eulogy he is seen writing in the first image of the film. It’s an uneasy choice for him to make. More problems arise when Francis (Pierre-Yves Cardinal), Guillaumes’s swaggering older brother, who still lives at home with his mother, struts into the kitchen bare-chested, seething with hostility towards the blonde urban interloper. Francis knew his brother’s secret life, has homophobic contempt for it, and has banned all of the gay friends from coming to the funeral (there’s a confrontation with one of them at the back of the church). Francis is so intimidating, so awful really, that it’s strange that Tom doesn’t just leave immediately after the funeral. But the farm exerts a pull on Tom (the real story of the film). Tom is hypnotized into the dysfunctional workings of the family, their subverted energies working on him like a drug. He can’t seem to leave. The only time he shows rage and frustration is when he is alone in his car after the funeral. Agathe becomes increasingly frayed. Francis picks fights with Tom, one particularly horrible one in the cornfield, with Tom getting torn to shreds by the razor-sharp dead corn stalks. In one terrible moment, Francis spits into Tom’s open mouth. But one day, Francis teaches Tom how to milk cows. Then another day, Tom helps birth a calf, and cries with emotion afterwards. Francis reveals that he used to take dance classes, and in one haunting scene, Francis and Tom ballroom dance through the empty barn, Francis dipping Tom back gallantly, the scene moving to romantic slo-mo.

What Dolan appears to be going for is a portrait of what could be seen as Stockholm Syndrome or perhaps the beginnings of a possible folie à deux situation. Francis and Tom hate each other, want to be each other, role-reverse, flirt, lash out. Tom is relatively submissive to Francis, taking the beatings, even encouraging them, and Francis senses that, takes pleasure in it. There’s a sexual dance going on throughout, reminiscent of the murdering duo Leopold and Loeb (especially in the portrayal of the characters in 1959’s “Compulsion”, highlighting the hypnotic cult-like Master-Slave dynamic), or the novels of Patricia Highsmith, filled with doubling isolated characters. Francis won’t let Tom leave, throwing obstacles in his way. Tom’s cell phone doesn’t work. He doesn’t just walk down to the main road and hitch a ride. He stays. Francis has no friends, Francis hates gay people, swaggers like a rooster, glories in his singularity. But Tom’s beautiful blank face before him is dying to be punched, or kissed, or marked in some way. These are the best sections of the film. It’s really the story, and Dolan’s intense interest in them is clear in the lingering way these scenes are shot.

But as the film continues on and on (it’s way too long), and Sarah (Evelyne Brochu), a city friend of Tom’s shows up, pretending to be the girlfriend in order to put Agathe’s mind at ease, “Tom at the Farm” unravels. There’s not enough structure to these different threads. It could work on the stage where movement and place and time are necessarily compressed, but on film it feels artificial, not fully worked out.

Beautiful visuals abound throughout (André Turpin, who also shot “Mommy”, is the cinematographer), and there’s a moody high-contrast look to the landscape (bright trees and bright corn behind dark shadows and fog) that speaks of secrets, torment, hope. The lush and heavy-on-the-strings score of Gabriel Yared is a clue to what Dolan was after. The score punctuates all of the scenes, casual or intense, adding portentous emotion, tension, fear of what is coming. It’s a melodramatic score, and “Tom at the Farm” works when it is a family melodrama. These are out-there people with outrageous emotional lives, subsisting on lies and denial, and the abyss between what they think their lives are and what their lives <i>really</i> are is enormous. All of them choose denial. They get tied to one another by their shared lies, and their unspoken agreement to keep on lying. The score supports that uneasy and terrible energy. The visuals, like the score, are exaggerated and stylistic, starting off with the helicopter shot following Tom’s car into the countryside, making him seem dwarfed by the surrounding land, a tiny figure entering an unknown isolated world. It’s a nod to Hitchcock or Kubrick.

The thriller elements, the chase scenes, the reveal of horrifying secrets, feel like add-ons, clumsily done and unmotivated, especially when compared to the dark and deep dance (metaphorical and literal) of violence and sex going on between Tom and Francis. That’s the real juice and guts of the film. It could be an answer to the nagging question throughout: Why the hell doesn’t Tom just leave? In thrillers, people are always making ridiculous choices that go against their self-interest, or ignoring the red flags in front of them of potential predators. In a well-done thriller, you mostly forgive the unreal quality of these moments. But “Tom at the Farm” does not foreground the thriller aspect enough (although the score tries mightily to do so), and so Tom doesn’t seem quite real. Nobody does.