We grow devout in the presence of poverty, particularly when it is not our own. We find an ennobling dignity in the lives of poor people, especially if they lived long ago and far away and don’t make any present demands on our time and money. There’s a natural tendency toward overcompensation when we see a movie like Ermanno Olmi’s “The Tree of Wooden Clogs.” We say the movie is a masterpiece when we mean that it is about people we pity and respect.

I can understand those reactions without sharing them. Olmi is going for broke in this film – he obviously intended it to be great, to dare everything – and because we are in sympathy with him we want to say he succeeds. But “The Tree of Wooden Clogs” demands a more complex response than that. If it is indeed very good, let’s not dismiss it with routine humanist overpraise.

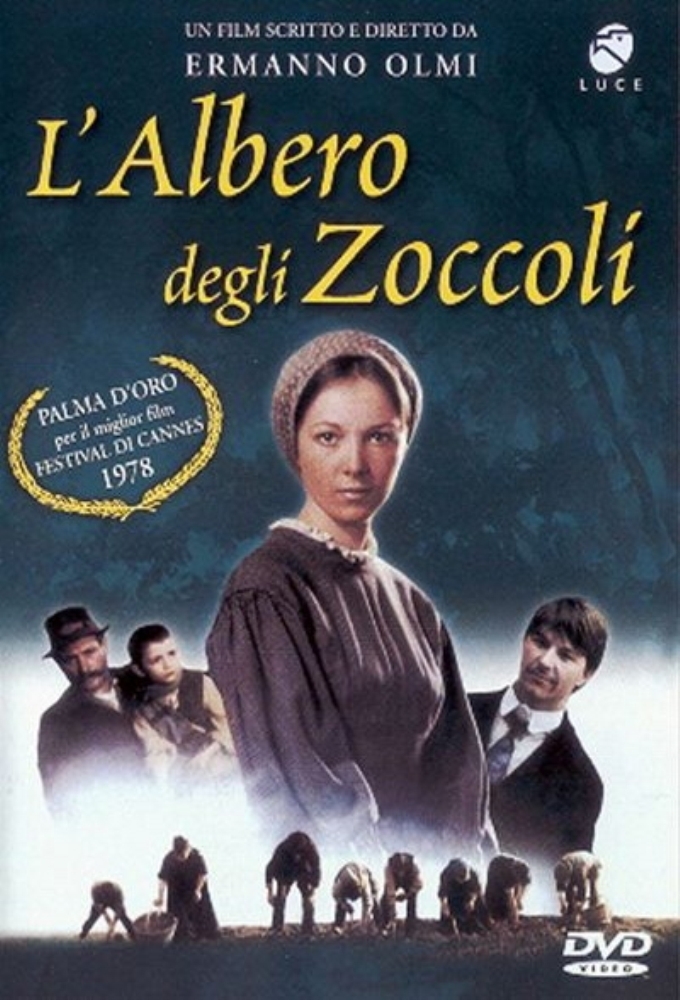

The movie’s set in Italy, in 1898, in a very poor country district where four peasant families live in the same farm complex and till the soil for the landowner, who gets three-quarters of whatever they do.

The lives of the families are very simple, centering around the change in the seasons, the condition of the soil, their own births and deaths and illnesses, their religion, their traditions. Somewhere else in Italy, a social revolution is growing and there are demonstrations in the streets, but to these peasants that is meaningless.

Olmi works very close to the land himself. He is in the neorealist tradition of DeSica, who experimented in “Shoeshine” and “Bicycle Thief” with the use of non-professionals. The people in “The Tree of Wooden Clogs” are not actors, we are told, but Olmi finds astonishing performances in them.

There are a lot of characters in the movie (which is three hours long), and we meet them in a series of many everyday activities. The fields are tilled, a hog is slaughtered, tomatoes are planted against the barn’s sunny wall. A child is born, a cow grows sick, a widow takes in laundry, a courtship proceeds, there is a fight, a wedding and a river journey to Milan, and one of the landowner’s trees is cut down to furnish wood for the clog sandal of a peasant child.

It is a very pleasant, even lulling, experience to watch these daily activities, and I found myself enjoying the film on a documentary level. Almost everything you might want to know about the external rhythms of Italian 19th century peasant life is here in this film, and, although Olmi is political and his film has a buried level of protest, this isn’t a leftist tract like Bertolucci’s “1900”; it’s the story of some lives.

But Olmi has a tendency to grow too sentimental about those lives. The film’s central image is of the peasant Batisti cutting down the poplar tree to make the sandal for his child. As he sits in his kitchen shaping the clog shoe, organ music by Bach plays on the soundtrack. And later the peasant family will be thrown off the land for stealing the tree.

As we wipe the tears from our eyes, may we also be permitted to reflect that (a) cutting down a whole tree is a rather drastic way to obtain the wood for one single clog shoe, and (b) that if Olmi’s reasoning is carried through to its conclusions, would we also get Bach playing over scenes of a modern Batisti sticking up a shoe store?

What I’m suggesting is that this movie should be viewed for its actual visual content, rather than for its noble pretensions. It is a film to experience in an almost apolitical way: We are introduced to a community of peasants, we observe their lives and strivings, Olmi has brought an astonishing wealth of detail, accuracy and beauty to this record of their story, and that is enough.