This will not do. It is like taking up the story of Salome after she has put the veils back on. Another problem is that there is not much action in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel, except inside the minds and souls of the characters. A third is that the Rev. Dimmesdale, who impregnates poor Hester, is the leader of the local hypocrites who persecute her. Channel surfing the other morning, I came across Demi Moore just as she was describing The Scarlet Letter as “a very dense, un-cinematic book.” And so it is; many of the best books are. That’s what rewrites are for. The film version imagines all of the events leading up to the adultery, photographed in the style of those “Playboy’s Fantasies” videos. It adds action: Indians, deadly fights, burning buildings, even the old trick where the condemned on the scaffold are saved by a violent interruption. And it converts the Rev. Dimmesdale from a scoundrel into a romantic and a weakling, perhaps because the times are not right for a movie about a fundamentalist hypocrite. It also gives us a red bird, which seems to represent the devil, and a shapely slave girl, who seems to represent the filmmakers’ desire to introduce voyeurism into the big sex scenes.

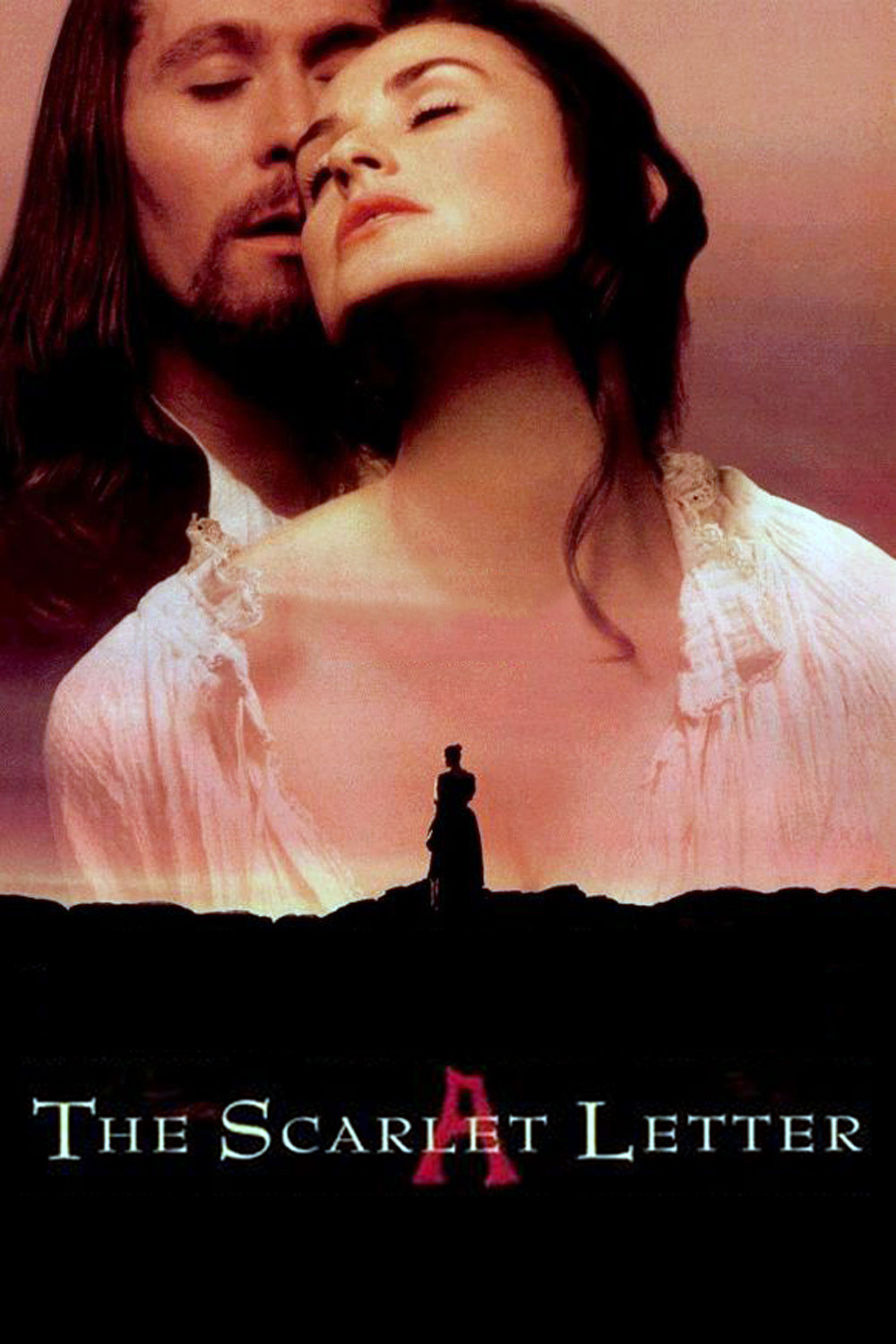

The story, you may recall, involves a Puritan woman named Hester Prynne (Demi Moore) who is found to be pregnant even though her husband has not arrived in the Massachusetts Bay colony and is feared dead.

After refusing to name the father of her child, Hester is condemned to wear a scarlet letter on her bodice. Her daughter Pearl is born, and grows up as a willful little vixen. It is revealed that the father of the child is Arthur Dimmesdale (Gary Oldman), leader of the local bluenoses denouncing Hester. And then her long-lost husband, Roger Prynne (Robert Duvall), turns up, assumes another identity and tries to determine who was the thief of his wife’s affections. The novel ends with poor Dimmesdale confessing his sin, crying out “His will be done! Farewell!” and dying.

It is obviously not acceptable for Dimmesdale to believe he has sinned, and so the movie cleverly transforms his big speech into a stirring cry for sexual freedom and religious tolerance. Instead of dying of a guilty seizure, he snatches the noose from Hester’s neck and pulls it around his own, only to be saved when the Indians attack, driving a burning cart through the village. The roles of the puritanical local ministers are farmed out to supporting actors, and Dimmesdale is left to hang around sheepishly, keeping his guilty secret but regarding Hester with big, wet eyes that beg for forgiveness and understanding.

Director Roland Joffe says “the book is set in a time when the seeds were sown for the bigotry, sexism and lack of tolerance we still battle today . . . yet it is often looked at merely as a tale of 19th century moralizing, a treatise against adultery.” Actually, it is more often looked upon as a tale of 17th century moralizing and a treatise against hypocrisy. But never mind. Joffe adds, “Of course, it is also a marvelous romance.” Not so marvelous, really. After insisting on a life alone in a cottage outside town, which sets local tongues a-wagging, Hester is walking in the forest one day when she comes upon a man skinny-dipping in a pond. It is the Reverend, although she doesn’t know that. She, and we, see him in the altogether, and then she hears him preaching in church, where he sounds a good deal more like Susan Powter than like a Puritan.

Hester entertains lustful thoughts about his body, and they entertain her. (Gary Oldman, marvelous actor that he is, may not be everybody’s ideal of the perfect male physique – remember him as Sid Vicious? – but on the whole I think we can be relieved Brad Pitt was not cast.) Hester’s comely slave girl, Mituba (Lisa Jolliff-Andoh), prepares her bath, and then Hester slowly luxuriates in it by candlelight, while dreaming of Arthur. It is hard to see for sure, but I think she may be indulging in the practice that the nuns called “interfering with herself.” Meanwhile, through a convenient peephole, Mituba watches lustfully, for no other purpose than to provide the additional thrill of one attractive woman observing another one naked. Will the sin that dare not speak its name make an appearance in Massachusetts Bay? Alas, no; the prospect of interracial lesbian love, appealing as it is to today’s filmmakers, would not quite fit into this story, even as revised and updated.

Soon Dimmesdale visits Hester, they become powerfully attracted to each other, and they commit adultery on a bed of dried beans in the shed. Mituba again watches them, disrobing and crawling into her mistress’ bath. Mituba holds a candle with its flame just above the waterline, and at the moment of their climax, she draws it under the water, extinguishing it with a hiss. This is much better than curtains blowing in the wind; it’s the equal of the moment in “Ryan’s Daughter” when, as the two lovers coupled, his stallion neighed and her mare whinnied.

The rest of the film is more or less as I have described it, although longer, much longer. Lurid melodrama develops after Hester’s husband arrives, played by Robert Duvall as if he’d never had sex in his life and didn’t want anybody else to partake, either. The movie’s morality boils down to: Why should this sourpuss stand between these two nice young people? The movie has removed the character’s sense of guilt, and therefore the story’s drama. (“Do you believe . . . what we did was wrong?” asks Hester.) Hollywood has taken that troublesome old novel and made it cinematic, although I’m afraid it’s still pretty dense.