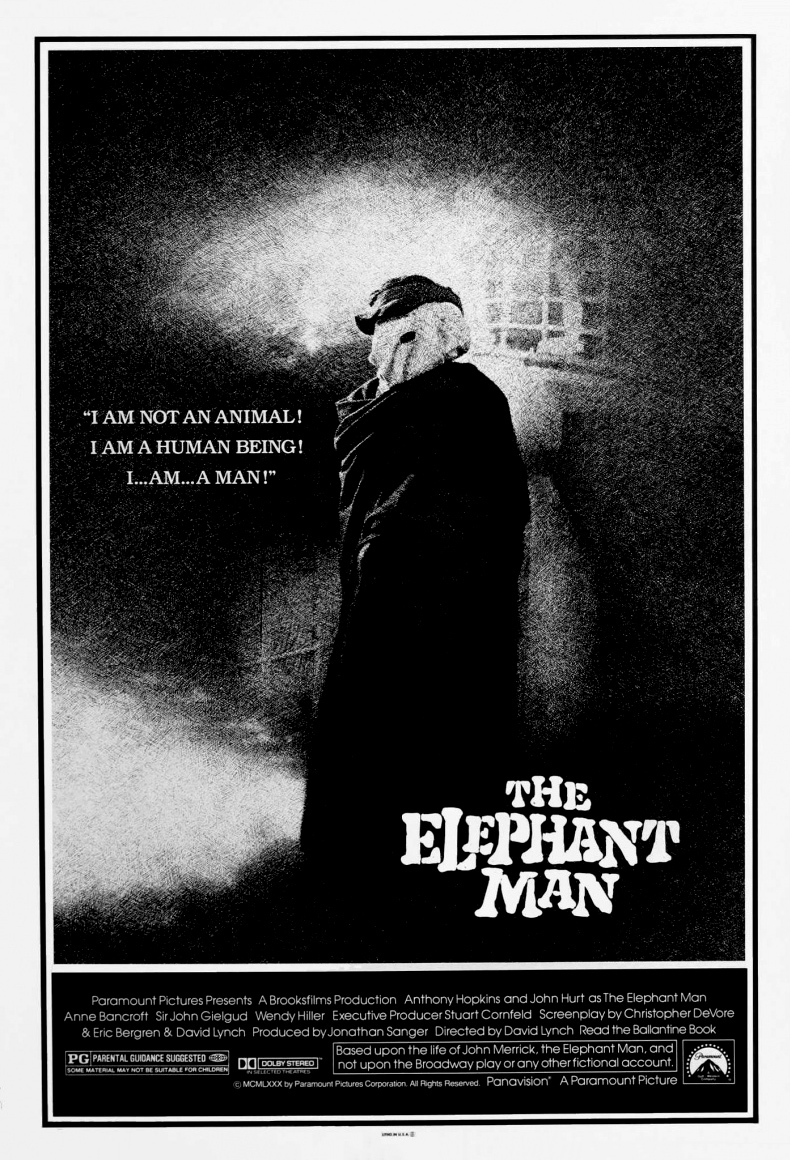

The film of The Elephant Man is not based on the successful stage play of the same name, but they both draw their sources from the life of John Merrick, the original “elephant man,” whose rare disease imprisoned him in a cruelly misformed body. Both the play and the movie adopt essentially the same point of view, that we are to honor Merrick because of the courage with which he faced his existence.

The Elephant Man forces me to question this position on two grounds: first, on the meaning of Merrick’s life, and second, on the ways in which the film employs it. It is conventional to say that Merrick, so hideously misformed that he was exhibited as a sideshow attraction, was courageous. No doubt he was. But there is a distinction here that needs to be drawn, between the courage of a man who chooses to face hardship for a good purpose, and the courage of a man who is simply doing the best he can, under the circumstances.

Wilfrid Sheed, an American novelist who is crippled by polio, once discussed this distinction in a Newsweek essay. He is sick and tired, he wrote, of being praised for his “courage,” when he did not choose to contract polio and has little choice but to deal with his handicaps as well as he can. True courage, he suggests, requires a degree of choice. Yet the whole structure of The Elephant Man is based on a life that is said tobe courageous, not because of the hero’s achievements, but simply because of the bad trick played on him by fate. In the film and the play (which are similar in many details), John Merrick learns to move in society, to have ladies in to tea, to attend the theater, and to build a scale model of a cathedral. Merrick may have had greater achievements in real life, but the film glosses them over. How, for example, did he learn to speak so well and eloquently? History tells us that the real Merrick’s jaw was so misshapen that an operation was necessary just to allow him to talk. In the film, however, after a few snuffles to warm up, he quotes the Twenty-Third Psalm and Romeo and Juliet. This is pure sentimentalism.

The film could have chosen to develop the relationship between Merrick and his medical sponsor, Dr. Frederick Treves, along the lines of the bond between doctor and child in Truffaut’s The Wild Child. It could have bluntly dealt with the degree of Merrick’s inability to relate to ordinary society, as in Werner Herzog’s Kaspar Hauser. Instead, it makes him noble and celebrates his nobility.

I kept asking myself what the film was really trying to say about the human condition as reflected by John Merrick, and I kept drawing blanks. The film’s philosophy is this shallow: (1)Wow, the Elephant Man sure looked hideous, and (2)gosh, isn’t it wonderful how he kept on in spite of everything? This last is in spite of a real possibility that John Merrick’s death at twenty-seven might have been suicide.

The film’s technical credits are adequate. John Hurt is very good as Merrick, somehow projecting a humanity past the disfiguring makeup, and Anthony Hopkins is correctly aloof and yet venal as the doctor. The direction, by David (Eraserhead) Lynch, is com-petent, although he gives us an inexcusable opening scene in which Merrick’s mother is trampled or scared by elephants or raped_who knows?_and an equally idiotic closing scene in which Merrick becomes the Star Child from 2001, or something.