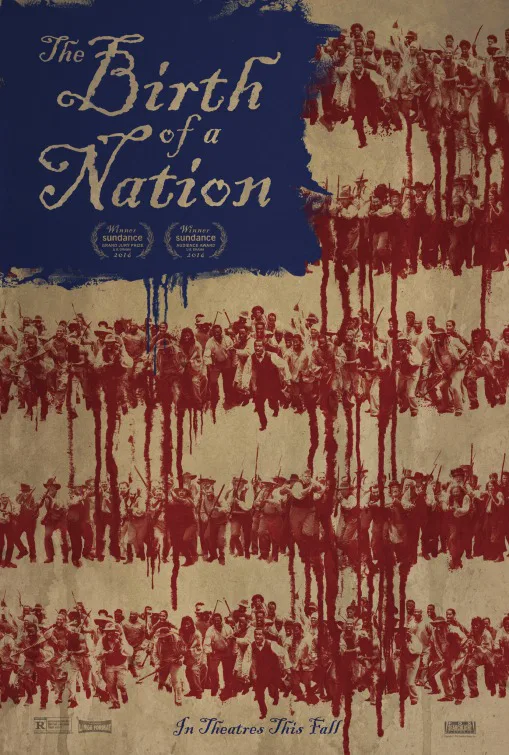

Nate Parker‘s “The Birth of a Nation,” a retelling of the 1831 slave rebellion led by Nat Turner, could not be more timely. The rise of Donald Trump and the more blatant expression of racist attitudes that his candidacy has emboldened; the outcry over police brutality and the formation of Black Lives Matter; the battles over hate speech, “safe spaces” and historical curriculum on campus; the debate about how to reform a criminal justice system that some believe is the continuation of Jim Crow by other means (see Ava DuVernay’s “13th” for more): these ongoing narratives all come back to the right to live an autonomous American life, and the duty to resist those who would oppose that right.

Turner is one of the earliest African-Americans to exemplify those qualities on the public stage, and he expressed them with such unrelenting violence that he’s still glossed over in many school textbooks. He and his followers—freed slaves who traveled from house to house, killing slave owners and their families, including children and infants, with farm implements—represented an Old Testament inversion of slave owners’ logic: Those who classify others as inhuman have relinquished the right to be thought of as human themselves. “The Birth of a Nation” is a revenge movie for an aggrieved time in U.S. history, when those who would “take back America” encounter widespread pushback from people who never got their turn at the wheel. The very title is an Information Age provocation: it’s the same name as D.W. Griffith’s formally innovative but KKK-glorifying silent epic, which means that anyone who searches for Griffith’s film on Google will come up with Parker’s as well. “This is a blow against white supremacy and racism in this country and abroad,” Parker told reporters at the Sundance Film Festival, where his independently funded debut premiered to a standing ovation and sold to Fox Searchlight for $17.5 million.

The real Turner was afflicted by visions that might have been diagnosed as mental illness. He spoke of communing with “the Spirit that spoke to the prophets in former days” and becoming inspired to lead a revolt to free his people. The movie’s Turner experiences all that and more. The screenplay treats him as a combination of Moses, Jesus and Sir William Wallace, a warrior-prophet who was identified as special from childhood, when a shaman practicing forbidden African religious rituals told him he was destined for great things.

The film sticks to the basics of a true story while crafting a righteous fable in which a sweetheart of a hero hallucinates himself as Christ and sees angels watching over him. It’s a “counter-myth”—to use the phrase Oliver Stone employed when defending “JFK” —designed to supplant Griffith’s. That’s fine; it’s part of a tradition as old as cinema—older, really.

But Parker pursues this strategy in such a simplistic way that you’re left with yet another movie about a speechifying avenger anointed by the cosmos. It’s a tale told with conviction but also tedious single-mindedness, as well as a self-regarding quality that makes the noble tone seem untrustworthy.

In the film, the adult Turner is specifically infuriated by the sexual abuse of women at the hands of white slaveowners. He has his first vision of blood when his wife Cherry Ann (Aja Naomi King) is beaten and raped by slave catchers, and is pushed over the edge when another woman, Esther (Gabrielle Union), is raped as well. The final third of the movie is a succession of small but intense skirmishes between Turner’s militia and local pro-slavery whites, including Jackie Earle Haley as a “paddy roller,” a blatantly racist policeman mainly concerned with protecting slave owners from slaves and preventing escapes. Turner is depicted as having the same motivation that drove the Klansmen in “The Birth of a Nation”: protecting women’s virtue.

Obviously, sexual exploitation was a huge motivating factor in this and other slave rebellions, as well as in peaceful forms of anti-slavery activism. But Parker’s film focuses on this element to the near-exclusion of everything else. As effective as this might be from an audience response standpoint, it does the real Turner a disservice, by flattening him out into a vigilante. The historical context, the visions, and the “He is Truly the One” prophecies thus feel grafted on to typical revenge-movie beats. The movie depicts resistance to oppression as a matter of male pride, and frames its horrors largely in terms of how upset they make Nat Turner/Nate Parker, glossing over the entrenched economic system that allowed white Americans to think of slavery as a simple fact of life—the “good German” mentality. (“12 Years a Slave” and both versions of “Roots” did a much better job with this aspect, while maintaining a populist touch.)

Like many Mel Gibson films, as well as such revenge-driven revisionist Westerns as “Posse” and “Django Unchained,” “The Birth of a Nation” is an intriguing object, passionate and furious and shameless and slick, distorting history in both defensible and problematic ways. (Gibson is one of Parker’s mentors and advised him on the script.) But the whole thing feels too much like an ad, hyping its filmmaker-writer-star as a freshly minted icon—an Orson Welles for the 21st century, or at least a Kenneth Branagh—and not enough like a thorough examination of its subject. You get less of a sense of what Turner’s historical period was like than you do about English occupied Scotland in “Braveheart,” which really isn’t saying much. Indeed, much of the movie seems less concerned with understanding Nat Turner, slavery and the Confederate South than glorifying Parker, who wears Turner’s capital-I Importance like a superhero cape.

From the low angles symbolizing heroism to the angel choirs on the soundtrack to the shots of actual angel figures (complete with Halloween costume wings), it’s a kitschy compendium of macho straight male actor-director signifiers: the kinds of touches that would be (and in some cases, have been) laughed off the screen if trotted out by an established star taking his turn behind the camera. (A whipping scene is staged like the one in “Glory” that won an Oscar for the director’s “Great Debaters” co-star, Denzel Washington—an actor whose gestures and vocal tics Parker too-knowingly evokes.) The real Turner was mysterious and terrifying even to those who knew and loved him. Parker’s version is a messianic cousin of The Nice Guy Pushed Too Far.

Parker’s approach turns the rest of the cast into glorified background for Turner, mere helpers whose only job is to inspire and embolden the hero. Union does her usual miraculous “something from nothing” acting; Armie Hammer has a few devastating scenes as Turner’s owner, who falsely believes himself more enlightened than other examples of his kind (the closest this movie comes to envisioning the wider context of Turner’s misery); and there are good bits scattered amongst the rest of the cast. But there’s ultimately room for only one fully imagined character here, the one played by the director and star.

And when it’s going gory and nasty, “The Birth of a Nation” is not going gory and nasty enough. Mel Gibson may be an ugly piece of work off-screen, but he’s a fire-and-brimstone storyteller, and there’s a hypnotic elegance to his bloodletting that is fascinating no matter what problems you might have with his films’ construction as drama. In “Braveheart,” “The Passion of the Christ” and “Apocalypto,” the directing itself seems possessed, guided by voices. A film about Nat Turner should go full Gibson. It should be dangerous, unstable, revelatory, and as scary and charismatic as Turner himself. It should go too far, then way too far, then keep going until, like some of Turner’s followers, you ask yourself if you even want to see this journey to its end.

Parker’s film lacks that kind of wild spark. It’s calculating, solemn and sincere: a For Your Consideration movie. Parker delivers filmmaking that’s effective but uninspired, like what you might encounter in a just-okay episode of “Game of Thrones”: some crane shots here; some assaultive flash-cuts there; jagged handheld camerawork for close-quarters fight scenes; sloshy-gushy sound effects when blood is spilled; the usual. Aside from a few poetic touches, such as the Terrence Malick-y images of canopied forests seen from ground level and a shot of an ear of corn welling up with blood (taken from Turner’s own statements), the film too often bludgeons and preaches when it should startle, challenge and mesmerize. Parker’s approach is never dull, exactly. But it’s never remarkable enough to overwhelm the suspicion that you’re not being told a story here so much as being sold a career.