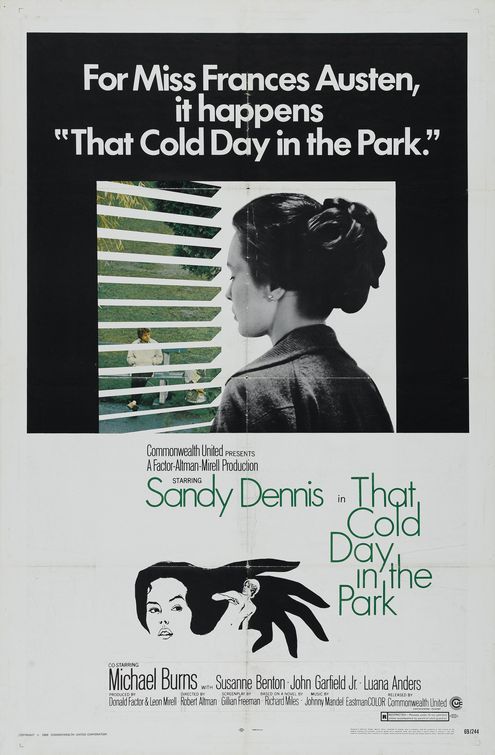

“That Cold Day in the Park” is one of those movies you can’t adequately discuss without using the word “see” as a refrain. There’s this spinster, see, and she finds this peculiar 19-year-old boy sitting in the rain in the park, see? And she invites him into her apartment, and it turns out that he never talks, and she’s a little weird herself.

Eventually, she locks him into a bedroom, but he leaves by the fire escape and meets his sister and her boyfriend, a draft dodger. And they turn on and then the guy returns to the apartment but things get complicated. And after his sister takes a bath in the spinster’s apartment and tries to seduce her brother, the spinster hires this prostitute and locks her in with the boy, after she (the spinster) has confessed her secret desires to what turns out to be a pillow and some blankets artfully arranged on the bed, see? And then she gets a knife out of the kitchen, and….

The plot is too improbable to be taken seriously, and yet director Robert Altman apparently does take it seriously. And so we get a torturous essay on abnormal psychology when, with less trouble, we could have had a simple, juicy horror film. There are some of the same exploitation angles as “Rosemary’s Baby” (clinical discussions of reproduction, an eerie apartment, strange games), but they just don’t work. In a straightforward horror movie, you can push pretty far before the audience starts laughing; they want to be scared. But “That Cold Day in the Park” doesn’t declare itself as a horror film until too late, and the audience is already lost.

In a famous little essay on detective novels, Raymond Chandler observed some years ago that it didn’t matter how well written a thriller was; what mattered was whether it worked. If it didn’t, the writing wouldn’t help, and if it did the writing didn’t matter. Much the same is true of horror movies; if they don’t work on the basic level of suspense, it doesn’t matter how well they’re done.

More’s the pity. “That Cold Day in the Park” is pretty well done. Sandy Dennis supplies a convincing portrait of the repressed, sex-obsessed spinster. Michael Burns is adequate as the boy, in a role that makes small demands on acting ability. Gillian Freeman’s script shows a good ear for dialog, especially during scenes in a birth-control clinic and a nightclub. And the photography by Laszlo Kovacs (who shot “Hell's Angels on Wheels” so well) does more than the direction or the script to establish a mood of approaching horror and tragedy. Too bad someone besides the cameraman wasn’t thinking in those terms.