The best of all vampire movies is “Nosferatu,” made by F.W. Murnau in Germany in 1922. Its eerie power only increases with age. Watching it, we don’t think about screenplays or special effects. We think: This movie believes in vampires. Max Schreck, the mysterious actor who played Court Orlock the vampire, is so persuasive we never think of the actor, only of the creature.

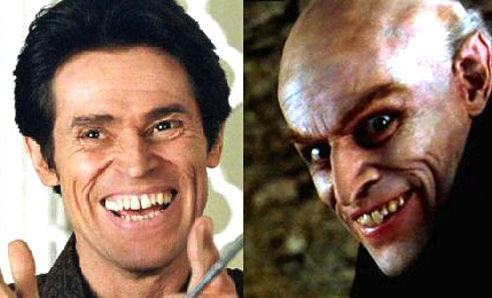

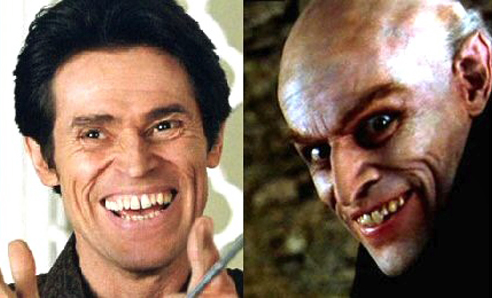

“Shadow of the Vampire,” a wicked new movie about the making of “Nosferatu,” has an explanation for Schreck’s performance: He really was a vampire. This is not a stretch. It is easier for me to believe Schreck was a vampire than he was an actor. Examine any photograph of him in the role and decide for yourself. Consider the rat-like face, the feral teeth, the bat ears, the sunken eyes, the fingernail claws that seem to have grown in the tomb. Makeup? He makes the word irrelevant.

In “Shadow of the Vampire,” director E. Elias Merhige and his writer, Steven Katz, do two things at the same time. They make a vampire movie of their own, and they tell a backstage story about the measures that a director will take to realize his vision. Murnau is a man obsessed with his legacy; he lectures his crew on the struggle to create art, promising them, “our poetry, our music, will have a context as certain as the grave.” What they have no way of knowing is that some of them will go to the grave themselves in the service of his poetry. He’s made a deal with Schreck: Perform in my movie, and you can dine on the blood of the leading lady.

John Malkovich plays Murnau as a theoretician who is utterly uninterested in human lives other than his own. His work justifies everything. Like other silent directors he has a flamboyant presence, stalking his sets with glasses pushed up on his forehead, making pronouncements, issuing orders, self-pitying about the fools he has to work with and the price he has to pay for his art. After we meet key members of the cast and crew in Berlin, the production moves to Czechoslovakia, where Schreck awaits. Murnau explains that the great actor is so dedicated to his craft that he lives in character around the clock and must never be spoken to, except as Count Orlock.

“Willem Dafoe is Max Schreck.” I put quotes around that because it’s not just a line for a movie ad but the truth: He embodies the Schreck of “Nosferatu” so uncannily that when real scenes from the silent classic are slipped into the frame, we don’t notice a difference. But he is not simply Schreck–or not simply Schreck as the vampire. He is also a venomous and long-suffering creature with unruly appetites, and angers Murnau by prematurely dining on the cinematographer. Murnau shouts in rage that he needs the cinematographer, and now will have to go to Berlin and hire another one. He begs Schreck to keep his appetites in check until the final scene. Schreck muses aloud, “I do not think we need . . . the writer . . .” Scenes like this work as inside comedy, but they also have a practical side: The star is hungry, and because he is the star, he can make demands. This would not be the first time a star has eaten a writer alive.

The fragrant Catherine McCormack plays Greta, the actress whose throat Schreck’s fangs will plunge into, for real, in the final scene. She of course does not understand this, and is a trooper, putting up with Schreck for the sake of art, even though he reeks of decay. Concerned about her closeups, intoxicated by the joy of stardom, she has no suspicions until, during her crucial scene, her eyes stray to the mirror–and Schreck, of course, is not reflected.

The movie does an uncanny job of re-creating the visual feel of Murnau’s film. There are shots that look the way moldy basements smell. This material doesn’t lend itself to subtlety, and Malkovich and Dafoe chew their lines like characters who know they are always being observed (some directors do more acting on their sets than the actors do). The supporting cast is a curiously, intriguingly mixed bag: Cary Elwes as Murnau’s cinematographer Fritz Wagner (not the one who is eaten), Eddie Izzard as one of the actors, the legendary Udo Kier as the producer.

Vampires for some reason are funny as well as frightening. Maybe that’s because the conditions of their lives are so absurd. Some of novelist Anne Rice’s vampires have a fairly entertaining time of it, but someone like Schreck seems doomed to spend eternity in psychic and physical horror. There is a nice passage where he submits to a sort of interview from his colleagues, remaining “in character” while answering questions about vampirism. He doesn’t make it sound like fun.

“Every horror film seems to become absurd after the passage of years,” Pauline Kael wrote in her review of “Nosferatu,” “yet the horror remains.” Here Merhige gives us scenes absurd and frightening at the same time, as when Schreck catches a bat that flies into a room and eats it. Or when Murnau, knowing all that he knows about Schreck, reassures his leading lady: “All you have to do is relax and, as they say, the vampire will do all the work.”