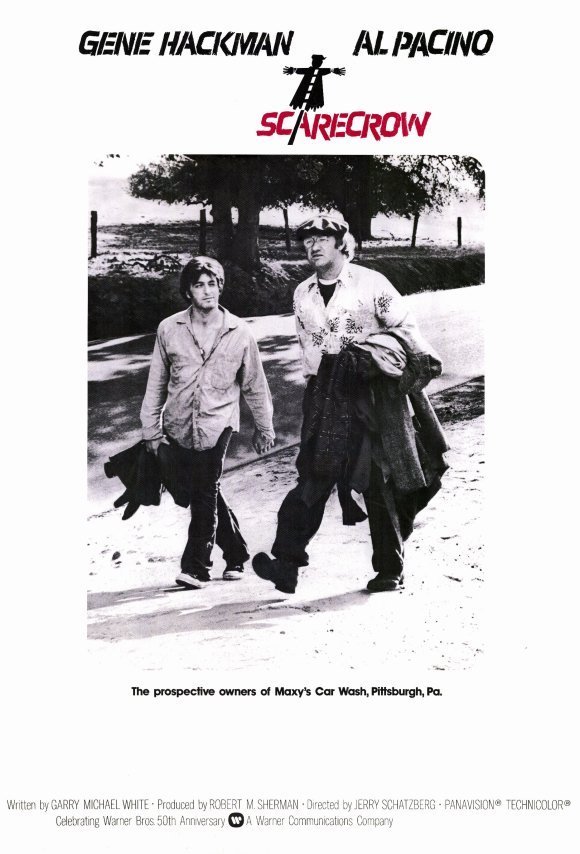

Max has been in the slammer and Lionel has been away at sea. Max has been sending his prison wages back to a savings and loan in Pittsburgh, and Lionel has been sending his to a wife in Detroit and a child he’s never seen. They hitch up on the Coast and hit the road with a dream of their own car wash with real nylon brushes.

It’s a trip we’ve taken before. We took it in “Of Mice and Men,” when there was a nice little farm at the end of the rainbow; we took it in “Easy Rider,” with the drug dealers who wanted to retire in Florida; we took it, most recognizably, in “Midnight Cowboy,” where the goal was those Florida orange groves.

Movies like “Scarecrow” (which shared the 1973 grand prize at Cannes) depend upon a couple of conventions. One is that we know more about the lower-middle-class characters than they know about themselves. The other is that we accept the easy rhythm of a picaresque journey without depending too much on plot.

“Scarecrow” doesn’t quite make it on either count, but it is a well-acted movie and for long stretches we’re hoping it will work. The performers are Gene Hackman and Al Pacino, two of the most gifted of contemporary actors, and the dialogue and locations (on the road, in taverns, at lunch counters, on a prison farm) strike a nicely realistic low key. But then director Jerry Schatzberg and his writer, Garry Michael White, commit the first of several mistakes: They tell us what the title means. The moment we hear the philosophy behind the scarecrow (he doesn’t scare the crows; he makes them laugh) we begin to suspect these characters are too conscious of their symbolic roles, and we’re right.

There’s another problem, too. Schatzberg, a celebrated photographer, has teamed up with Vilmos Zsigmond (“McCabe and Mrs. Miller“) to produce a movie so obsessed with its visual look that it suffers dramatically. The movie is annoyingly lighted; we constantly seem to be peering through fog at the characters. In a scene or two, this could be nice. At almost two hours, it’s an affectation. So is Schatzberg’s willingness to allow shots to continue at length; an opening conversation at a lunch counter runs maybe three or four minutes. It’s a virtuoso piece of acting by Hackman and Pacino, but after a while the shot calls attention to itself and away from them.

Still, there are fine moments, as there would have to be with Hackman and Pacino. There’s a scene in a bar when a would-be fight turns into a comic striptease by Hackman. There’s a bittersweet interlude with Max’s sister and her girlfriend. And there are times of just rambling, as the two friends depend on each other in a big and lonely world. It’s too bad everything is brought together to a big, smashing, dramatic crisis at the end; “Scarecrow” somehow should have drifted out on a lower key.