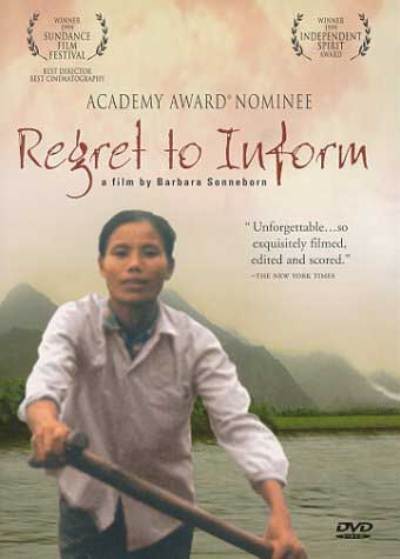

“We had talked about the possibility of Jeff dying,” Barbara remembers, in the narration of “Regret to Inform.” “We never talked about the possibility that he would have to kill.” After his death, she received a tape recording he had made. It took her 20 years to work up the courage to listen to it. On it, she heard his voice saying he felt like a bystander to his own life–“watching myself do things I never expected or desired to do.” Sonneborn enlists as a translator a woman named Xuan Ngoc Evans, who has memories of her own. One of them is of the day when her 5-year-old cousin darted out of a safe place to get a drink of water and was shot dead by a GI. “I remember how his eyes looked,” she says. “He had a horrified look in his eye, as much as I did.” This woman later worked as a prostitute, dating American soldiers. “I wouldn’t have,” she says, “if I’d had another choice.” The distinctive thing about Sonneborn’s film, which won awards for best documentary and best cinematography at the 1999 Sundance festival, is that it remembers the war from both sides, as seen by the women who were touched by it. We meet the widow of a Native American rodeo cowboy, who signed up over her protests because it was his duty. And the widow of a man killed by Agent Orange, the defoliant the United States tried to deny was harmful.

And there is the woman who so desperately wanted to deflect her husband’s desire to serve that she considered injuring his hand with a hammer. “I wanted to stop him and I thought of smashing his hand, doing it the right way, so it would take six months to heal, time for our baby to be born.” Sonneborn, her translator and small crew take the train from one end of Vietnam to another. They talk to Vietnamese war widows. One remembers hiding under a pile of corpses because to be dead was to be safe. The film makes little distinction between the widows of soldiers who died fighting for the south or the north. All of the memories are painful.

The movie takes pains to remain at the personal level; for women whose husbands fought on opposing sides, the war today is not a political dispute but a huge force that swept away their men, the fathers of their children. Left unsaid is what we see in the background. Vietnam today is independent and communist, the two things the U.S. fought to prevent, yet it is not regarded as a dangerous enemy, but a popular tourist destination for Americans–many of them, like Sonneborn, going back looking for answers.

There is one moment in particular that will stay with me a long time. Sonneborn goes to visit the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., and talks to a woman who weeps that her husband’s name is not included. “My husband should be on the wall,” she says. “He left his soul in Vietnam. It took his body seven years to catch up. He went out in the garage and shot himself. He left a note that said, “I love you sweetheart, but I just can’t take the flashbacks anymore.’ “