To make a broad but useful generalization: Before “Look Back in Anger” (1958), most British films were more or less traditional comedies, dramas, thrillers or what have you. Since then, a generation of inventive young directors has found the freedom to make movies about, and against, key aspects of their society. The better films they’ve produced since 1958 seem to fall roughly into two classes.

First there were the films of working-class realism, inspired by the “angry young men” playwrights, authors and directors in revolt against the Conservative establishment then running the country. Their heroes were workingmen who couldn’t care less what happened east of Suez, and their credo was expressed nicely in “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning” when Albert Finney snarled: “All I’m out for is a bloody good time, and you can take all the rest and shove it.”

Memorable films of this period included “A Taste of Honey,” “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner” and “This Sporting Life.” They were often about men who knew something was dreadfully wrong with their lives — that some essential ingredient was missing — but who felt incapable of changing themselves and sought refuge in bitterness, a fierce rejection of Establishment values, and marathon bouts of drinking and wenching.

In the end, these refuges proved inadequate, and most of the working class films brought their heroes full-circle. The last frame of “A Taste of Honey” shows Rita Tushingham wistfully absorbed in a toy sparkler; children play around her, but she will never again know their joy and optimism. At the end of “Long Distance Runner,” Tom Courteney deliberately loses the race, which could win him the warden’s favor. He does not want to perform for the Establishment: he would rather be an outsider.

Most of these films were based on a feeling of impotence; there didn’t seem to be any way out of society’s trap, and in any event there was nothing an individual could do. But with the beginning of the Kennedy years here and the election of the Labor government in Britain, the workingman’s predicament became less popular as a plot subject. In a way, it was old-fashioned anyway.

What had happened was that the intellectuals no longer felt barred from the centers of power. Norman Mailer has written that when Kennedy was elected, he felt able to have an influence again through his writing — instead of through ban-the-bomb demonstrations and other dead ends. In England, where most of the writers and directors considered themselves socialists, the Labor victory posed a similar question: Now that “our crowd” is in power, whom do we blame for what’s wrong?

The new target, as it turned out, was “our crowd” itself. The young British directors turned to comedy, aiming it at the conventional pieties of their society. They used black comedy, sick comedy, wildly satirical comedy, comedy designed to undermine hypocrisy as directly as possible.

The victims of this new comedy were not fat policemen, officious nurses, blueblooded aristocrats and Terry-Thomas, but the middle class, the intellectuals and their own most treasured prejudices. The turning point probably came in 1963, when director Tony Richardson abandoned working-class subjects and made his first comedy, “Tom Jones.” It was a landmark film, in which traditional ways of making commercial movies were left behind. Broad farce went side-by-side with serious social comment and total irreverence. Albert Finney was an embittered workingman no longer, but a jolly dropout who made asides directly to the audience so they could share the fun.

“Tom Jones” was followed by many satirical comedies: “Morgan,” “Georgy Girl,” “Darling,” “A Hard Day's Night,” “Alfie” (1966), “The Knack” and “Bedazzled” (1968) for starters. Many only seemed to be funny. Beneath Georgy Girl’s ugly duckling act and Alfie’s carefree amorality, you could find a serious criticism of the hero’s life and times.

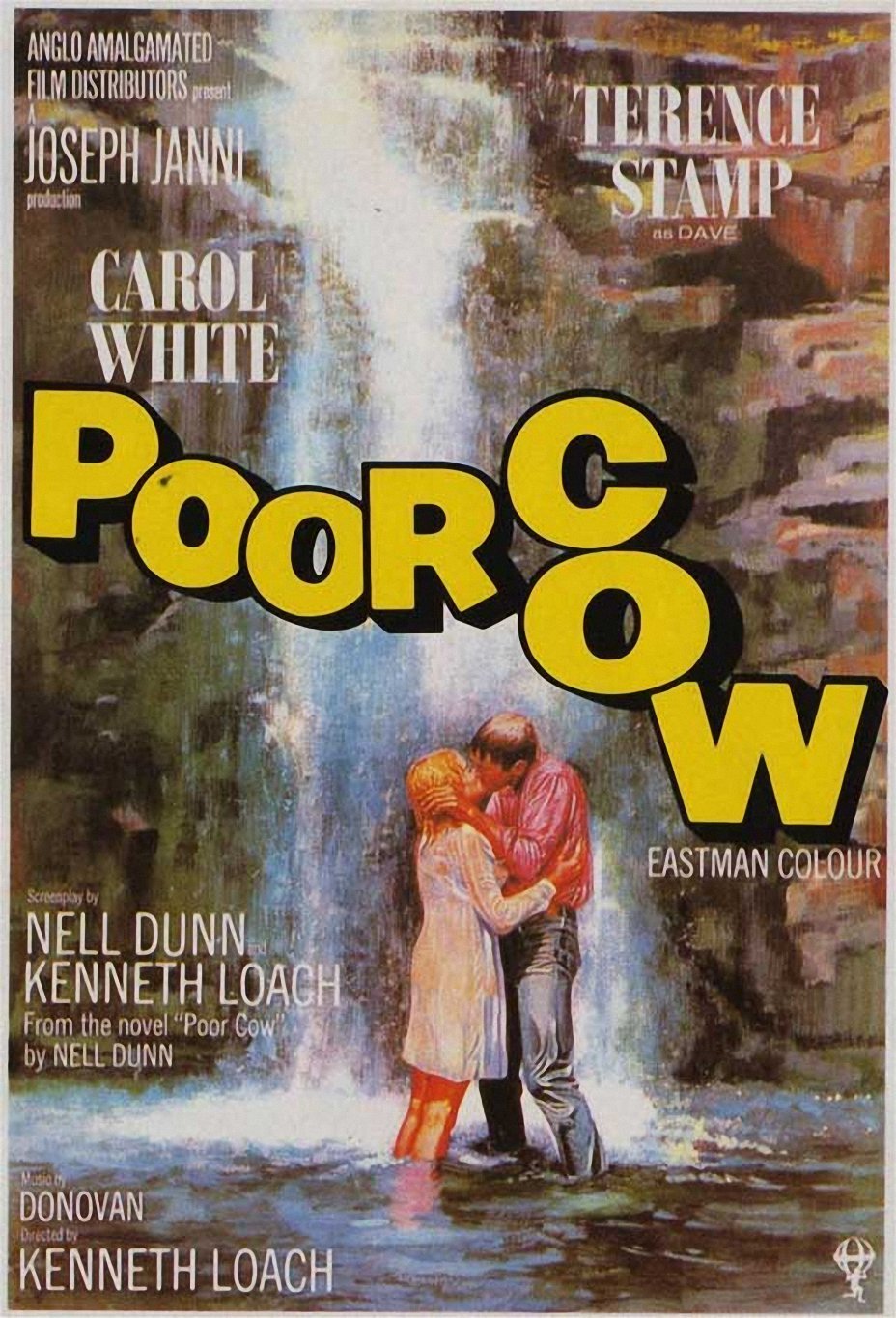

All of this is in preface to some remarks about “Poor Cow,” which isn’t a very good movie but is extremely interesting in terms of what is happening now in the British cinema. “Poor Cow” may be an advance sign that we are entering a third phase in recent British films.

After the social realism and then the satire, here comes a film made in equal parts of squalor and techniques. Like Peter Collinson’s recent “The Penthouse,”‘ it wants to offend us at least as much as it wants to amuse and educate us, and it seems part of a new anger appearing among artists in England and America. Its director, Kenneth Loach, supplies a venomous, unforgiving examination of British life and offers not a shred of hope for the future. His approach avoids the message and social significance of the working-class films, while borrowing their subject matter. It also avoids the humor of the new comedies, while borrowing their subversive, irreverent attitudes.

Perhaps this can be read as an indication that things no longer seem funny in England. The devaluation of the pound and the general directionlessness of the Labor government, for which so much was hoped, seem subjects for bitterness rather than fun. Seen against a back drop of other sore points for British leftists — Rhodesia, Vietnam, racist immigration policies — Loach’s ill will and his readiness to offend his audiences may be an approach we can expect to see more of.

“Poor Cow” is patterned after “Darling” in a way. Its producer, Joseph Janni, also produced that one, and its star, Carol White, looks enough like Julie Christie to be her twin sister (the one who couldn’t act). Both Darling and Poor Cow were girls who cold-bloodedly used their bodies to get what they wanted from the world. But there, the resemblance ends.

For one thing, the heroine of “Poor Cow” doesn’t achieve much satisfaction or happiness. As a lower-class female, trapped in an environment where ex-convicts and sleazy pub-crawlers are considered good catches, she is literally a cow. Her purpose, once the dreams have been stripped away, seems to be fundamental: She satisfies men and she bears children. Life holds absolutely nothing else for her or for other “poor cows” trapped in her situation. She does not realize her full hopelessness, however, justifying it in terms of her neurotic need for constant male companionship (“Any man will do,” as the ads say).

There is, as I have suggested, no message in this movie, despite its promising subject. This is not necessarily a fault. Mark Twain offered to shoot anybody finding a moral in “Huckleberry Finn.” But a film’s message need not be obvious. It can consist simply of the director’s attitude toward his material, conveyed by the way he tells his story. This is Godard’s approach, except when he starts making political speeches.

Loach apparently doesn’t have an attitude, however, and seems unable to decide what his story of Poor Cow means. This confusion is buried beneath technique and permissiveness. He plays with his camera and lets his actors run wild. There’s lots of hand-held camera work, lots of playing with the focus while shooting into the sun, lots of lyrical passages in which Donovan sings while the screen runs over with pretty pictures and even chapter titles (borrowed from Godard) which are flashed on the screen to begin each episode.

When Richard Lester uses gimmicks like this (in “The Knack,” for example) they seem to add up to an attitude. When Loach uses them, they seem little more than exercises. They are all the more distracting because the performances don’t absorb us. With the exception of Terence Stamp, who is excellent as the girl’s sensitive but irresponsible lover, there is no one in the movie who should be trusted out from under the director’s thumb. Yet Loach allows them semi-improvised scenes that mostly fall flat (and in which the other male lead, John Bindon, proves himself incapable of improvising so much as a sneeze).

In the end, the few good moments (as when the girl tends bar, cares for her child and shares confidences with Terence Stamp) are lost in the mess of everything else. The movie doesn’t work, and like all movies that don’t work it seems long and boring. Still, it may be the forerunner of a new attitude from England. If you’re interested in movies, by all means see this one. It will give you more to talk about than most successful films.