“In order that I exist,” the narrator of “Oscar and Lucinda” tells us, “two gamblers, one obsessive, one compulsive, must declare themselves.” The gamblers are his grandparents, two 19th century eccentrics, driven by faith and temptation, who find they are freed to practice the first by indulging in the second. Their lives form a love story of enchantment and wicked wit.

When we say two people were born for each other, that sometimes means their lives would have been impossible with anyone else. That appears to be the case with Oscar and Lucinda. Their story, told as a long flashback, begins with Oscar as the shy son of a stern English minister, and Lucinda as the strong-willed girl raised on a ranch in the Australian outback. We see them formed by their early lives; he studies for the ministry, she inherits a glassworks and becomes obsessed with glass, and they meet during an ocean voyage from England to Australia.

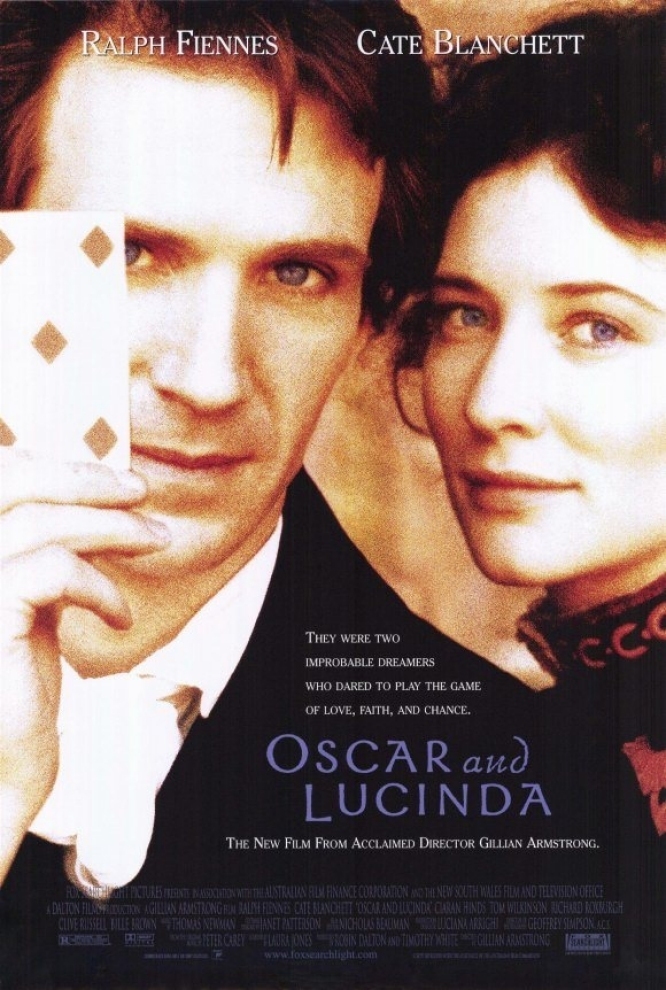

They meet, indeed, because they gamble. Oscar (Ralph Fiennes) has been introduced to horse racing while studying to be a clergyman, and is transformed by the notion that someone will actually pay him money for predicting which horse will cross the line first. Lucinda (Cate Blanchett) loves cards. Soon they’re playing clandestine card games onboard ship, and Oscar is as thrilled by her descriptions of gambling as another man might be by tales of sexual adventures.

“Oscar and Lucinda” is based on a novel by Peter Carey, a chronicler of Australian eccentricity; it won the 1988 Booker Prize, Britain’s highest literary award. Reading it, I was swept up by the humor of the situation, and by the passion of the two gamblers. For Oscar, gambling is not a sin but an embrace of the rules of chance that govern the entire universe: “We bet that there is a God–we bet our life on it!” There also is the thrill of the forbidden. Once ashore in Sydney, where Oscar finds rooms with a pious church couple, they continue to meet to play cards, and when discovered, they’re defiant. Oscar decides he doesn’t fit into ordinary society. Lucinda says it is no matter. Even now they are not in love; it is gambling that holds them together, and Oscar believes Lucinda fancies another minister who has gone off to convert the outback. That gives him his great idea: Lucinda’s glassworks will fabricate a glass cathedral, and Oscar will superintend the process of floating it upriver to the remote settlement.

For madness, this matches the obsession in Herzog’s “Fitzcarraldo” to move a steamship across a strip of dry land. For inspiration, it seems divine–especially since they make a bet on it. Reading the novel, I pictured the glass cathedral as tall and vast, but of course it is a smaller church, one suitable for a growing congregation, and the photography showing its stately river progress is somehow funny and touching at the same time.

“Oscar and Lucinda” has been directed by Gillian Armstrong, whose films often deal with people who are right for each other and wrong for everyone else (see her neglected 1993 film “The Last Days of Chez Nous,” about a troubled marriage between an Australian and a Frenchman, or recall her 1979 film “My Brilliant Career,” in which Judy Davis played a character not unlike Lucinda in spirit). Here there is a dry wit, generated between the well-balanced performances of Fiennes and Blanchett, who seem quietly delighted to be playing two such rich characters.

The film’s photography, by Geoffrey Simpson, begins with standard, lush 19th century period evocations of landscape and sky, but then subtly grows more insistent on the quirky character of early Sydney, and then cuts loose altogether from the everyday in the final sequences involving the glass church. In many period films, we are always aware that we’re watching the past: Here Oscar and Lucinda seem ahead of us, filled with freshness and invention, and only the narration (by Geoffrey Rush of “Shine“) reminds us that they were, incredibly, someone’s grandparents.

“Oscar and Lucinda” begins with the look of a period literary adaptation, but this is not Dickens, Austen, Forster or James; Carey’s novel is playful and manipulative, and so is the film. Oscar is shy and painfully sincere, Lucinda has evaded her century’s strictures on women by finding a private passion, and they would both agree, I believe, that people who worship in glass churches should not throw stones.