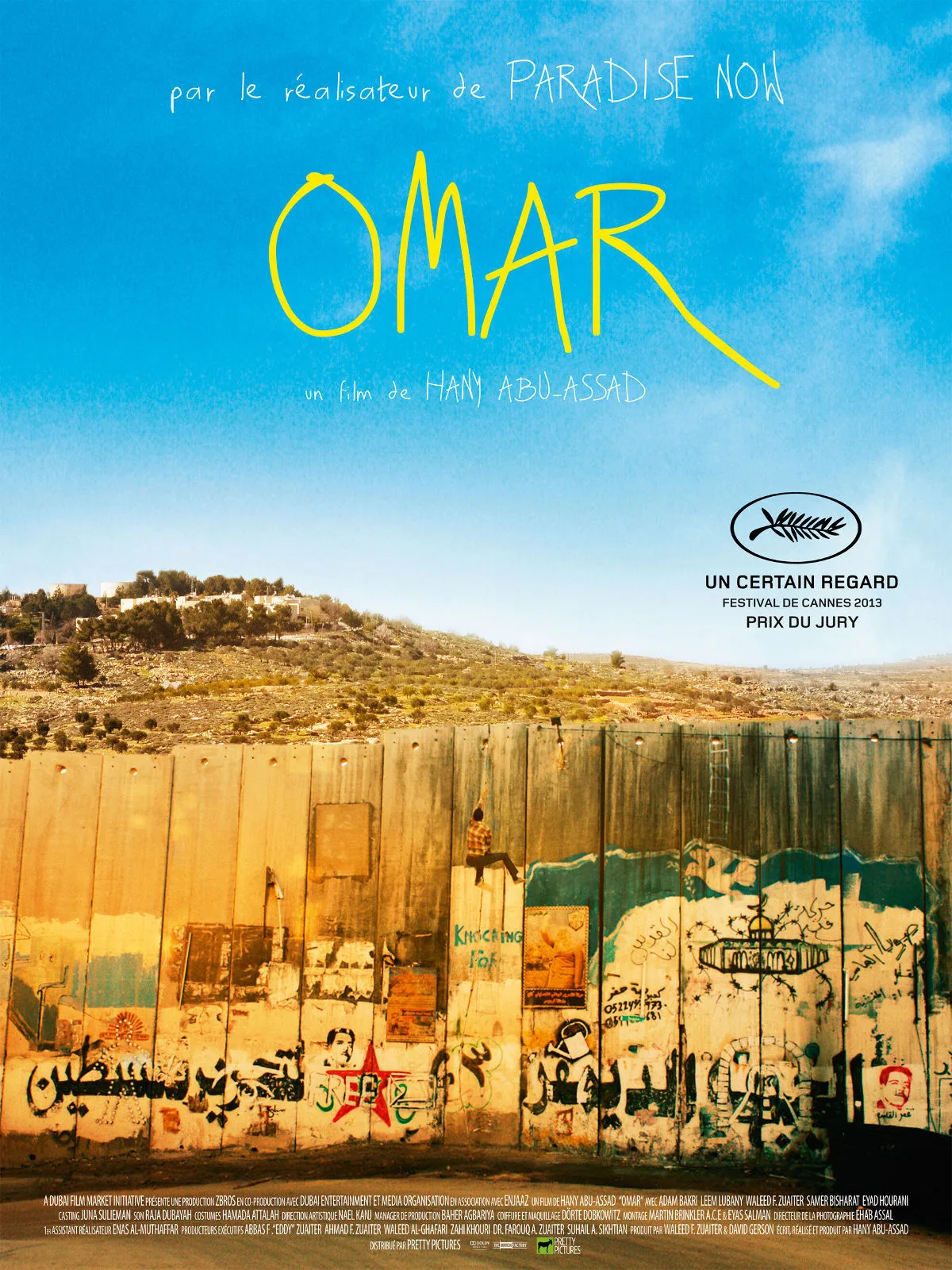

The separation wall runs through occupied Palestine, intimidating and omnipresent, covered with snarky graffiti, reminiscent of the Berlin Wall in its final days. A striking image of the wall opens Hany Abu-Assad‘s Oscar-nominated film “Omar”, Abu-Assad’s first Palestinian feature since “Paradise Now” in 2005. Omar (Adam Bakri) is seen grappling up a dangling rope, scaling the sheer face of the wall, before scrambling over to drop down to the other side. The wall will be used again and again in “Omar”, first to show Omar’s training as a revolutionary (once he gets out of practice, it becomes a huge struggle to make it up that wall), and also to symbolize the ways that the wall separates Palestinians not only from Israelis but also from one another. The wall makes things like love, loyalty, connection and intimacy impossible.

“Omar” is a thriller and a romance with unabashedly melodramatic elements (there’s even a love triangle), all of which are brought into stark relief by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Helped along by an amazing cast of mostly first-time actors, “Omar” feels very fresh due to its attitude, approach, and the fact that it offers no solutions. It’s the story of three childhood friends caught up in a war that seemingly has no end. They are torn between their individual desires to have a home, a girlfriend, a family, and their devotion to the freedom of Palestine. In such an atmosphere, their best qualities will be used against them; their love for one another makes them vulnerable to betrayal.

Omar is played by Adam Bakri, a new actor with barely any credits. He is open, accessible, handsome, and incredibly physical; the film requires him to run, leap and tightrope-walk his way along high walls. Omar is a baker, who spends his free time training for an upcoming operation against the Israelis with his two childhood friends, Tarek (Eyad Hourani) and Amjad (Samer Bisharat). They appear to be working independently of any established group. Later, when Omar is in prison, one of the other prisoners says to him, by way of introduction, “I’m with Hamas. What group are you with?” Being part of a group gives you protection and legitimacy, but Omar is more of a street kid, doing target practice in the woods with his two pals. Their plan is to kill an Israeli soldier in a nearby garrison, an act both reckless and meaningless. But they feel powerless, and the daily humiliations they endure, including random stop-and-searches, have taken their toll. They feel the need to do something to participate in the fight.

Amjad is the one who pulls the trigger, killing a random Israeli soldier. Omar is chased through the streets the following day and finally arrested and brought to prison. Into the film strolls Agent Rami (the fantastic Waleed F. Zuaiter), who had posed as an Arab prisoner at first, striking up a gentle conversation with Omar in the prison cafeteria, in which Omar says the fateful words, “I will never confess.” This, of course, is seen as a confession, and Omar is strung up naked in a pitch-black interrogation room and tortured. He is finally offered a deal by Agent Rami: They will release Omar on the condition that Omar will hand them Tarek. Omar is devastated and panicked, and yet hopeful that he can work both sides.

Omar’s main source of happiness before his imprisonment was Nadja (Leem Lubany), the younger sister of Tarek, the leader of their little street gang. Omar and Nadja meet secretly, passing notes to one another when they think no one is looking. They make tentative plans to get married, shyly looking at a one-roomed apartment together, unable to say the words “the bed can go here” without blushing. They have to keep their relationship a secret because their world is so traditional, and they are both so young. There is a fondness, affection and teasing humor in their dynamic that is heart-rending and sweet, adolescent and optimistic, and while it is obviously doomed, you don’t know from where the doom will come. As Omar’s situation becomes more and more dangerous, and as Omar’s reputation becomes tarnished, Nadja starts to fear for her life. She wonders if it’s true what is being whispered in the alleyways of her neighborhood. If Omar is collaborating with the Israelis then he is not the man she thought he was.

Love is not easy in the best of times, but in the worst of times it is flat-out dangerous. Being a warrior requires hardness and emotional armor. Omar is not hard. He is open and vulnerable, and those qualities are his very best. He is kind, funny, easygoing, and able to give himself over to love fully. It’s not an overstatement to suggest that these are the qualities that make him a credit to the human race and its positive potential. Without those qualities, we are all doomed. But such openness cannot be allowed to flourish in a treacherous war-torn atmosphere where betrayal is required. Betrayal is the theme of the film. Omar is forced to betray his political convictions, in order to work with Agent Rami (their couple of scenes together are among the best in the film), and Nadja struggles with betrayal as well as her loyalties start to shift.

Hany Abu-Assad is, of course, interested in the situation of Palestine, and how the occupation impacts the lives of the people who live there. In “Omar” he rejects the macro view, and stays strictly within the micro, keeping close to his main character, observing the daily rhythms of the occupation, and the daily weirdness of living under the shadow of that huge wall. The larger concerns of a group like Hamas are nearly invisible. Early in the film, we see the three friends letting off steam together—throwing around dirty jokes, Amjad entertaining them with his hilarious Marlon Brando imitation (it is pretty funny)—and it slowly becomes impossible to imagine the friends ever finding their way back to such an innocent dynamic. That is what is lost in such a war. That is what is sacrificed. The war seeps down into the molecules, the spaces in-between language. It is in people’s thoughts and dreams. When Omar and Nadja discuss escaping that world together after marriage they can barely imagine leaving their neighborhood. Those dreams hover, like a mirage. Maybe they’d like to go to Paris, but you see they can’t really believe in it.

The separation wall is not just a hated structure in the Palestinian landscape. It is within the hearts and minds of the characters. And that’s the tragedy.