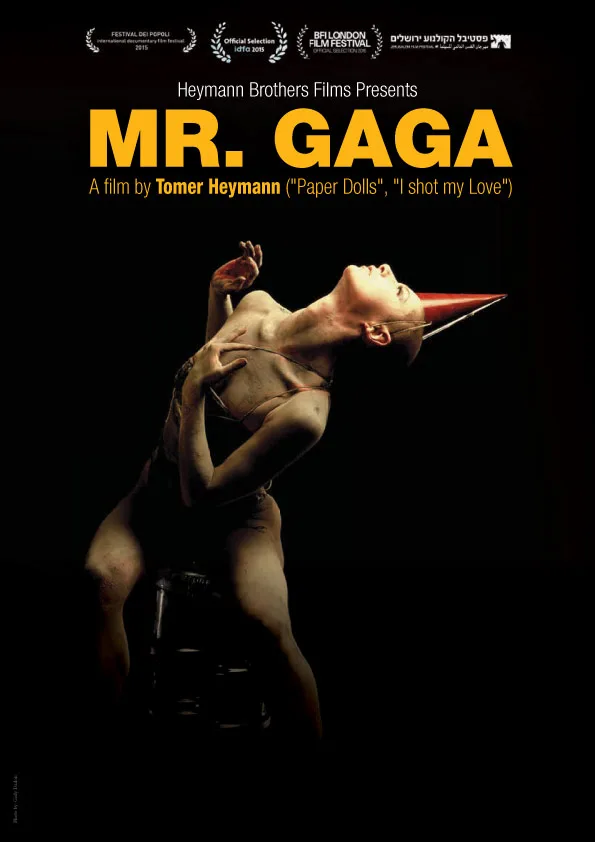

Israeli choreographer Ohad Naharin, the subject of Tomer Heymann’s documentary “Mr. Gaga,” is movie-star handsome in a craggy-faced intense way. The dancers who have worked with him say he is intimidating. He has ideas and emotions he wants to communicate and is looking for the dancer who understands without having to be told. During one group audition for his company, Batsheva Dance Group, he watches one of the dancers in the midst of the large crowd, musing in voiceover, “I can see her body has limitations, but she is a poet.” In his choreography, Naharin blends the visceral with the abstract and intellectual, and is a compelling subject all on his own, a man of alternate withholding and stark honesty. “Mr. Gaga” is an intense pleasure: the extensive footage of Naharin’s choreography in performances over the years, beautifully captured by Ital Rziel, gives an intimate and thrilling glimpse of what he is all about. Naharin’s work is distinct. You could recognize it in a lineup.

Naharin grew up on a kibbutz, and served in the Israeli Army (in the entertainment division) during the Yom Kippur War. He came to formal dance training late, in his mid-20s, and he looks at this as an asset. There is a bit of an outsider about him. He had “something” as a dancer, an animalistic sinewy quality to his body and an inventiveness with movement that left people breathless. One of his early dance teachers admits that she had moments teaching him “that I had never had as a dance teacher.” The first big change was when Martha Graham came to Israel to choreograph something, and she fell for him. Not hard to understand why. He was a hunk, and “she liked pretty boys,” says Naharin openly. She took Naharin back to New York with her to work in her company. He only lasted 10 months. But he made an impression on everyone. The documentary is filled with interviews of company members and dance teachers who speak of his “rarity,” how his onstage persona was an electric blend of masculine and feminine. He was aggressive and pliable simultaneously. Naharin and his wife Mari Kajiwara, a star dancer with the famed Alvin Ailey company (who quit Ailey to join her husband’s fledgling company) ended up moving back to Israel to run Batsheva Dance Group.

His work did not catch on immediately with Israeli audiences. It’s challenging and sometimes confrontational work; it demands engagement from its audience. Many people, especially traditionalists, were turned off. But a controversy involving the dance he choreographed for the 50th anniversary celebration of the creation of the state of Israel put him on the front pages. Religious groups objected to the revealing nature of the dancers’ costumes, and called for more modesty. Rather than cave to the fundamentalists and alter the costumes, Naharin pulled his troupe from the celebration at the last minute, refusing to perform. He became a national hero in that moment, representative of artistic freedom and the fight against censorship and religious zealots. His work began to catch on.

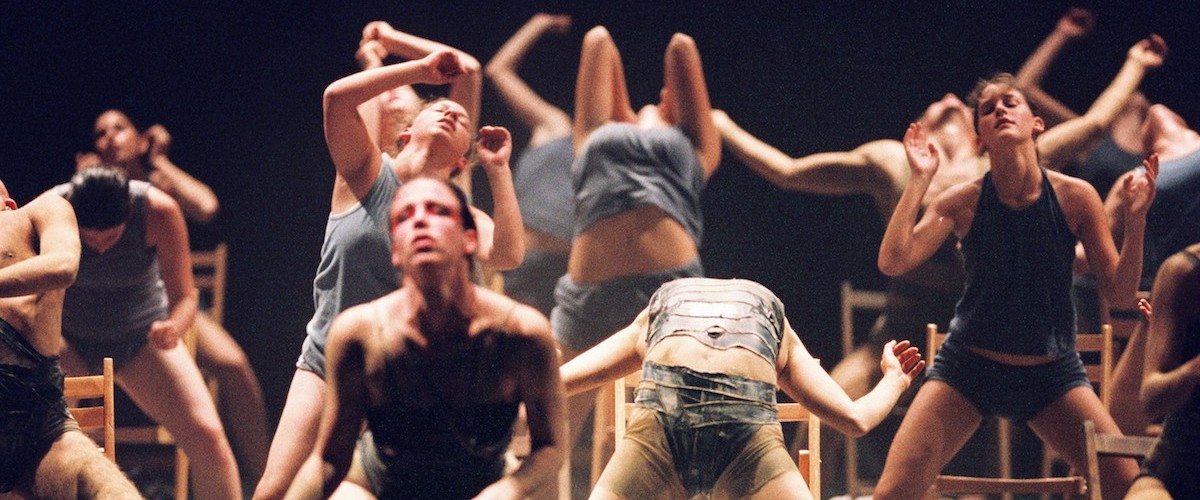

“Mr. Gaga” is filled with home movies from Naharin’s childhood and grainy footage of Naharin’s dance shows in early 80s New York. These are beautiful additions, since Naharin himself remains—almost to the very end—a somewhat mysterious figure (and not an altogether reliable narrator, as he admits at one point late in the film). There are audition sequences, rehearsal sequences. “Mr. Gaga” is a superb dance documentary in its almost single-minded focus on process. Watching Naharin work with his dancers is fascinating. He is a powerful and sometimes frightening taskmaster, but when a dancer “gets it” he laughs in delight. He gives extremely specific instructions. During one rehearsal, Naharin suggests that when the dancers do the wildly swinging arm movements, they think of swinging a hammer and pounding in a nail. The dancers try it. Something is missing. Naharin adds to the instruction, “If you hammer this nail, you will save someone’s life.” And you then see the transformation, the movements sparking off the screen in group commitment and urgency. It’s thrilling. He tells one dancer that he does not want her to change the shape of the movement, but change it within: “Exaggerate the movement inside your skin.” Naharin’s choreography often includes objects: duct tape, water bottles, gigantic chalkboards, a treadmill. His first solo show included a grocery cart and 100s of cans of Pepsi Cola. His choreography require “groupthink,” the company moving as one, sometimes quickly, sometimes slowly, on intricate buried counts. Heymann uses many cameras to film Naharin’s dance works, some placed out in the theatre to give the wider perspective, other cameras on the stage. Naharin’s work often incorporates haunting optical illusions, and Heymann’s approach is extremely sensitive in that regard. It’s the next best thing to being there in the room. There are images created by Naharin’s company that I will not soon forget.

Naharin seems like an unlikely emeritus figure, but that is what he has become. He gives huge open classes in “gaga” all around the world—all age groups, all body types. (There’s wonderful footage of these classes. They look like glorious fun.) Unfortunately, it’s never really clear what “gaga” actually is, even though everybody talks about it constantly. Naharin says it connects “effort and pleasure,” it helps us “go beyond our familiar limits.” Natalie Portman shows up in a brief interview, describing her experiences in his open class, but she doesn’t say what “gaga” actually is either. This was a little frustrating since the term is referenced so often. But Naharin’s choreography—captured so gorgeously by Heymann—speaks for itself.