A lot of movies are said to be timeless, but somehow in their immortality they fail to draw audiences. They lead a sort of half-life in film society revivals, and turn up every now and then on the late show. They’re classics, everyone agrees, but that word “classic” has become terribly cheap in relation to movies. It’s applied so promiscuously that by now the only thing you can be sure of about a “film classic” is that it isn’t actually in current release.

One of the many remarkable things about Charlie Chaplin is that his films continue to hold up, to attract and delight audiences. Chaplin hasn’t really been active in movies for 20 years, aside from “A King in New York” in 1957 and the unfortunate “A Countess from Hong Kong” five years ago. The millions of followers and fans who cheered him in his Little Tramp days are now mostly a memory; if 85 per cent of the American movie audience is under 35, as industry statistics claim, then 85 per cent of Charlie’s original audience must probably be over 35.

So his decision to release a series of his best films must have sometimes seemed like a risk. His name is enshrined among the greatest geniuses of film; the French have a movie magazine titled simply Charlie, and Vachel Lindsay said a long time ago, “The cinema IS Chaplin.” He had proven his greatness in every possible way; but then, at 81, he decided to put some of his films on the market again and see how they fared.

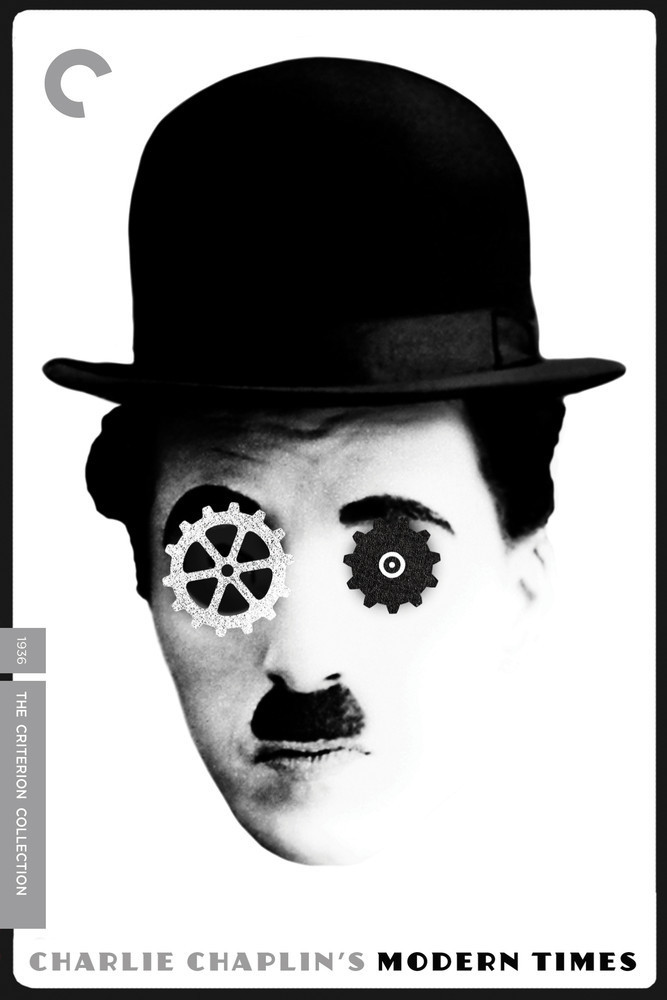

They are faring very well, you might say. Here in Chicago they’ve been booked in the Carnegie Theater, where the staff hardly knows what hit it. “Modern Times” (1936), the first of seven Chaplin programs, was SRO all weekend, and when I saw it on Sunday afternoon, the audience was just about beside itself with delight.

I go to a lot of movies, and I can’t remember the last time I heard a paying audience actually applaud at the end of a film. But this one did. And the talk afterward in the aisles, the lobby and in line at the parking garage was genuinely excited; maybe a lot of these people hadn’t seen much Chaplin before, or were simply very happy to find that the passage of time have not diminished the man’s special genius.

“Modern Times” was Charlie’s first film after five years of hibernation in the 1930s. He didn’t much like talkies, and despite the introduction of sound in 1927, his “City Lights” (1931) was defiantly silent.

With “Modern Times,” a fable about (among other things) automation, assembly lines and the enslaving of man by machines, he hit upon an effective way to introduce sound without disturbing his comedy of pantomime: The voices in the movie are channeled through other media. The ruthless steel tycoon talks over closed-circuit television, a crackpot inventor brings in a recorded sales pitch, and so on. The only synched sound is Charlie’s famous tryout as a singing waiter; perhaps after Garbo spoke, the only thing left was for Charlie to sing.