After Florence Foster Jenkins gave a concert at Carnegie Hall in 1944 (she rented the venue herself), Earl Wilson, the gossip columnist for the New York Post, observed drily, “She can sing anything but notes.” Despite her notoriously screech-owl tones, Jenkins seemed to truly believe she was a brilliant coloratura soprano, and moved through the world in uninterrupted delusion. The crowds who flocked to her recitals watched with awed fascination, thinking, “Am I allowed to laugh at this? Is she in on the joke?” There are YouTube clips of her recordings. You may wonder, “How bad could she be?” Very, very bad as it turns out.

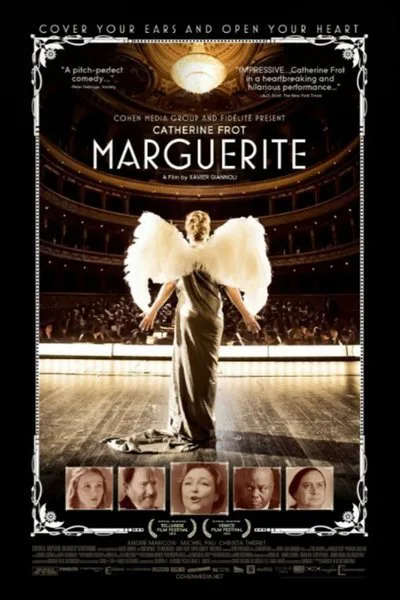

The César-winning “Marguerite,” directed by Xavier Giannoli, moves the action to France, and features a riveting performance from Catherine Frot as Marguerite. The script (co-written by Giannoli and Marcia Romano) disintegrates in the too-lengthy final act, and an “explanation” is provided for what has really been going on with Marguerite all along. The explanation is a disappointment and not nearly as interesting as the main question that buzzes through the film, experienced by every person who comes into contact with Marguerite: Does she know how bad she is? How … how can she not know?

It’s 1921. Marguerite Dumont lives on an estate in the French countryside with her husband Georges (André Marcon). She is an active member of the Amadeus Music Club (they depend on her financial support) and serves as the headliner for their concerts. Georges writhes with embarrassment at his wife’s insistence on singing publicly, but he has never pulled her aside in their 20 years of marriage and said, “Honey, you stink.” How can he break the news to her now? He is filled with guilt. He hides in his study. He watches her run around the yard in a Brünnhilde costume and knows he has helped create the lunatic asylum in which he lives.

The opening sequence of “Marguerite,” an Amadeus Club charity concert on the Dumont estate, is well-done, and Giannoli artfully creates a buildup of expectation for Marguerite’s solo (it is as though Maria Callas herself is about to appear). The main characters, those who will be drawn into Marguerite’s circle, are introduced: Lucien, a young journalist (Sylvain Dieuaide); Lucien’s monocle-wearing anarchist friend Kyril (Aubert Fenoy); Hazel (Christa Théret) a young conservatory student. Marguerite, peacock feather on the top of her head, glides through the crowded room, taking her place by the piano. It is as though she is used to singing for Shahs and Emperors. And then she launches into Mozart’s tremendously difficult “Queen of the Night,” and you hear the voice for the first time.

Catherine Frot’s valiant attempt to make it through that song is high comedy, but not just because of how badly she sings. It is clear that Marguerite knows what the song should sound like, and to her tone-deaf ears she sings it beautifully. The best part of Frot’s performance, and the key to why “Marguerite” works when it does work, is how totally Marguerite believes in her nonexistent gift. Her manner is not imperious. She’s as enthusiastic as a little girl. Her bows are the deep humble bows of a grande dame. Frot’s Marguerite is a character study that refuses to explain all, even when the plot shovels in a disappointing explanation. Frot is so good that you understand why people who initially snicker (Lucien, Kyril, Hazel) come to care for her, even feel protective of her.

Everyone erects a bubble of encouragement around her. The tone is set by Madelbos (Denis Mpunga), the intimidating Dumont butler, who acts as a fortress. Even Georges is afraid of Madelbos. Madelbos organizes photo shoots for Marguerite, roping in the house servants as costumed extras. He’s so terrifying that just a glance from him stops people from expressing anything other than glowing praise.

Marguerite decides to put on a recital in a public venue, and, with the help of Lucien, hires washed-up opera singer Atos Pezzini (Michel Fau) as a vocal coach. Pezzini is first seen onstage, grotesquely over-emoting as Pagliacci in a performance Marguerite thinks is marvelous. Pezzini scoffs at the thought of coaching an amateur, but he needs the money. He shows up at the Dumont house for their first session, so over-dressed and dandy-fied he looks like one of Tenniel’s exaggerated drawings. Pezzini’s stone-faced and yet panicked reaction to Marguerite’s first note is the funniest moment in the film. Only his eyes move, flitting left, then right, like a trapped animal. The voice is hopeless, yet he throws himself into getting her into shape, in a “training montage,” where he makes Marguerite gyrate her hips, rub her breasts, sing into a wall, and lie on the floor with giant books on her abdomen.

The ultimate question, the one that grounds “Marguerite,” is: What is it like to love music as much as Marguerite Dumont and yet have no talent? But plenty of people love music passionately, can’t sing a note, and don’t lose one wink of sleep about it. You don’t need to be able to sing “Queen of the Night” to appreciate it. Marguerite is reminiscent of Amanda Wingfield in Tennessee Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie,” so certain that a gentleman caller will arrive to court her disabled daughter that she will impale herself, and her family, on that doomed hope. Her life depends on it. So does Marguerite’s.

“Marguerite” is not afraid to laugh at its title character, but, and this is credit to both Giannoli and Frot, the film does not ask the audience to sneer at her. Yes, you want her to stop singing immediately because her lack of talent is titanic, but you don’t want people to be mean to her. If someone had said to Marguerite early on, “Listen. You can’t sing,” would it have made a difference? Would she have been happy? But Marguerite is undeniably happy when she sings. It’s an ethical quandary, one the film has a lot of fun exploring.

Anyone who has watched “American Idol” is familiar with the expression of incomprehension on the faces of some contestants when they are given blunt criticism by one of the judges. The contestants sound awesome to themselves. They think that imitating Christina Aguilera’s trills, or Beyonce’s vibrato, is enough. They think that if they want it badly enough, they should be able to have it. But art, especially singing, is a meritocracy. It’s unfair, but there it is. If you need Auto-Tune to correct every other note, maybe you don’t have an aptitude for music. Dreams die hard, though. Delusions die even harder.

“Marguerite” is too long, and the final section devolves into an entirely different film. The urge to “explain” Marguerite proved irresistible, but some things just can’t be explained.