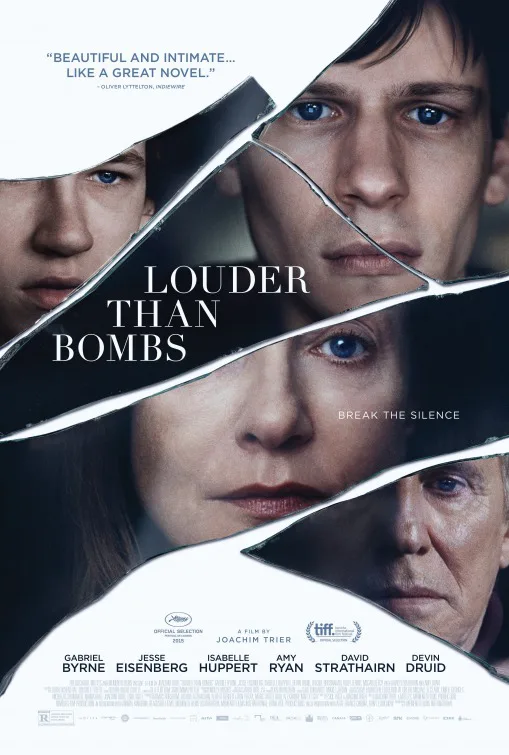

Joachim Trier’s “Louder Than Bombs” is interested in the intersection between grief and memory, and how difficult it is to capture both either through photography or film. It is a movie that comments on its own purpose (as co-writer Eskil Vogt’s “Blind” did as well) by making one of its most essential characters a conflict area photographer, someone who once lamented the difficulty in maintaining focus on the specific people she chronicles and not turning them into universal examples. Trier, a masterful filmmaker who has already delivered must-sees in “Oslo, August 31” and “Reprise,” navigates an incredibly tricky minefield of mourning, regret and the detailed minutiae that makes up our lives. It is a statement on life and death that opens with a newborn baby’s hand but is primarily about how we process loss. Sometimes its meandering approach can feel a bit more detached than in Trier’s best work, but this is ultimately a delicate, complex film that lingers, unpacking itself in your mind. You remember it in the same kind of fragmented images that haunt its characters.

The baby hand belongs to the new son of Jonah (Jesse Eisenberg), a birth that has turned his father Gene (Gabriel Byrne, doing his best work since “In Treatment”) into a grandpa and his brother Conrad (Devin Druid) into an uncle. The arrival of a new branch in this family tree spurns memories of the lost matriarch of this clan, Isabelle (Isabelle Huppert), but it also sends Jonah off on his own unique path. Major events like birth and death have a way of redefining the way we perceive the world, and not in a treacly moral-message-movie way, but even in just the way we practically interact with one another. Perhaps realizing that being a father really closes a chapter on his youth, Jonah rekindles an affair with someone from his past, a woman named Erin (Rachel Brosnahan), who happens to be losing her mother.

Meanwhile, the younger Conrad is adrift. He doesn’t have many friends in high school, and can’t connect with his father, who is hiding the fact that he’s sleeping with Conrad’s teacher, Hannah (Amy Ryan). Gene tries to call Conrad, and even follows him around town to see what he’s doing. When he reaches him and asks him where he is, Conrad, sitting alone on a swing set, lies and says he’s with friends. It breaks a father’s heart. Conrad is fascinated by a girl in his class named Melanie (Ruby Jerins), sometimes even thinking she’s the magical key to his future. Trier’s film even dips into magical realism, such as when Conrad moves his hand like a magician and Melanie’s hair blows in the wind. Sometimes, especially in our most egocentric teen years, we think we can make the object of affection’s mind move because want it to. In a sense, the world revolves around Conrad—his unaware crush, his avatars in the online game he plays every night, his grief over the loss of his mother—and his journey in “Louder Than Bombs” is one of learning that other people have needs, wants and secrets as well.

A story is coming out in the New York Times that will tell “the true story” about Isabelle, who died in a car accident. Did she kill herself? Was she meeting a lover? Jonah and Gene know the truth but have kept it from Conrad, and they disagree over whether or not he’s ready to learn it.

How do we remember those we lost? It’s often not like the big moments of typical Hollywood cinema but a minor one, like Conrad’s beautiful memory of his mother pretending not to see him hiding behind some clothes on a line. And how do we capture grief? Can photography, fiction or film possibly convey that which cannot really be put into words? Trier wisely knows the limitations of his form, even including a line like, “Mom once showed me how she could change the meaning of a picture by framing it differently.” He has not made a movie that purports to have any answers, doing what Isabelle did in that he frames a specific story for universal purpose.

Trier’s film is at its best when it’s graceful and simple. Working with regular cinematographer Jakob Ihre, he’s very interested in the humanity of his characters, returning to images of hair, eyes, kissing mouths. The film is surprisingly striking visually, finding beauty in both cheerleader bodies hurtling through the air and a car that has just crashed head-on into a truck. Ola Fløttum’s minimal, effective score works subtly to add another layer of grief that doesn’t feel manipulative or overdone.

Sometimes Trier’s approach can edge into directionless and I wanted parts of “Louder Than Bombs” to feel more emotionally raw. It’s a film that’s remarkably interior, as Jonah and Conrad’s internal monologues are raging in ways that an author would be able to convey but a filmmaker has to find different ways to do so. In one remarkable scene, Jonah reads aloud a collection of notes that his brother has saved on his laptop about random feelings, stats about his day, and general details of life. Sometimes Trier’s film feels like a riff on that document, capturing fragments of memory for the record. When it’s done, Jonah says something else that feels like a meta-commentary on the film itself: “It’s really weird, but interesting. It’s really … it’s really good.”