Arthur Penn’s “Little Big Man” is an endlessly entertaining attempt to spin an epic in the form of a yarn. It mostly works. When it doesn’t — when there’s a failure of tone or an overdrawn caricature — it regroups cheerfully and plunges ahead. We’re disposed to go along; all good storytellers tell stretchers once in a while, and circle back to be sure we got the good parts.

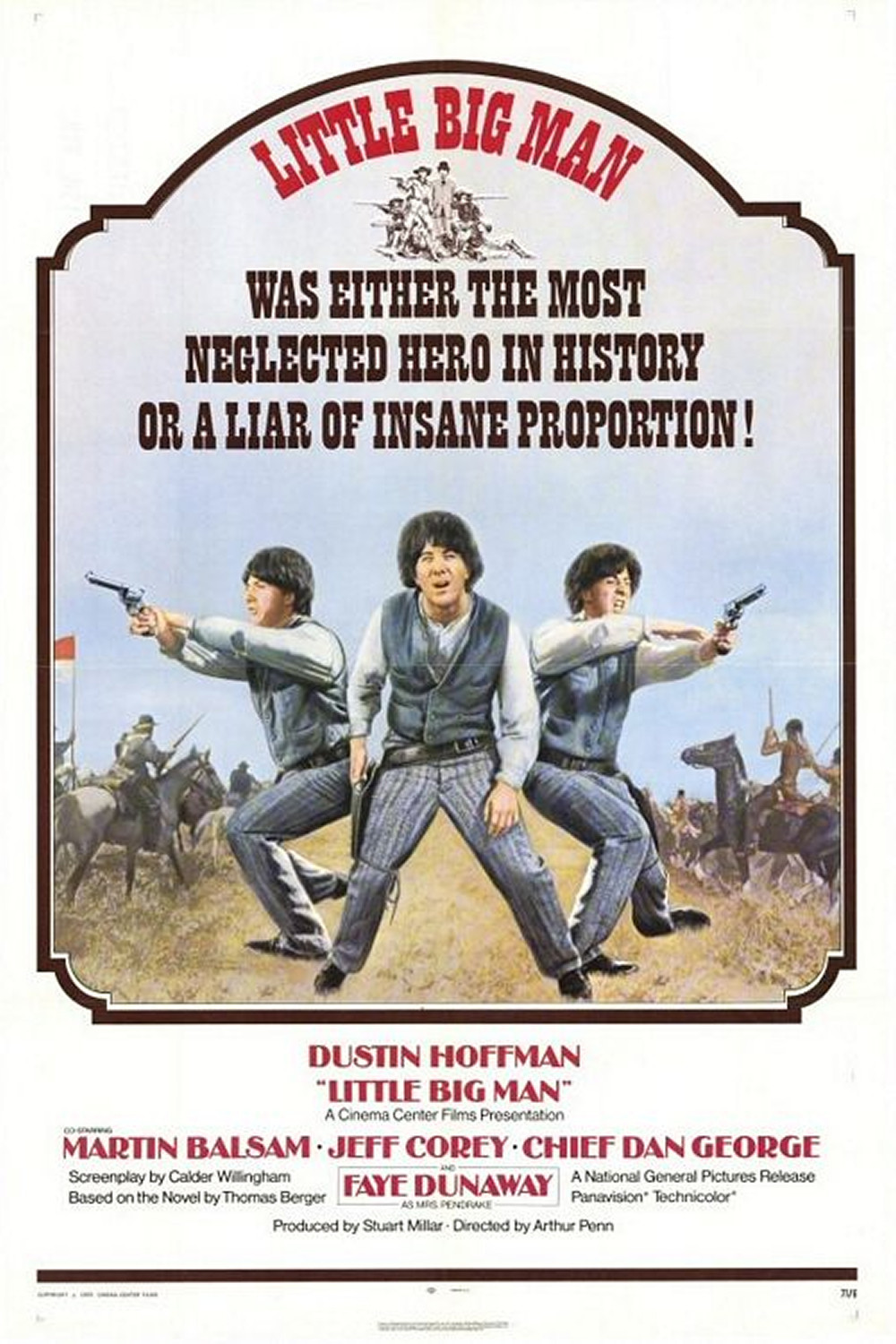

It is the very folksiness of Penn’s film that makes it, finally, such a perceptive and important statement about Indians, the West, and the American dream. There’s no stridency, no preaching, no deep-voiced narrators making sure we got the point of the last massacre. All the events happened long, long ago, and they’re related by a 121-year-old man who just wants to pass the story along. The yarn is the most flexible of story forms. Its teller can pause to repeat a point; he can hurry ahead ten years; he can forget an entire epoch in remembering the legend of a single man. He doesn’t capture the history of a time, but its flavor. “Little Big Man” gives us the flavor of the Cheyenne nation before white men brought uncivilization to the West. Its hero, played by Dustin Hoffman, is no hero at all but merely a survivor.

Hoffman, or Little Big Man, gets around pretty well. He touches all the bases of the Western myth. He was brought West as a settler, raised as a Cheyenne, tried his hand at gunfighting and medicine shows, scouted for the cavalry, experimented with the hermit life, was married twice, survived Custer’s Last Stand, and sat at the foot of an old man named Old Lodge Skins, who instructed him in the Cheyenne view of creation.

Old Lodge Skins, played by Chief Dan George with such serenity and conviction that an Academy Award was mentioned, doesn’t preach the Cheyenne philosophy. It is part of him. It’s all the more a part of him because Penn has allowed the Indians in the film to speak ordinary, idiomatic English. Most movie Indians have had to express themselves with an “um” at the end of every other word: “Swap-um wampum plenty soon,” etc. The Indians in “Little Big Man” have dialogue reflecting the idiomatic richness of Indian tongues; when Old Lodge Skins simply refers to Cheyennes as “the Human Beings,” the phrase is literal and meaningful and we don’t laugh.

Despite Old Lodge Skins, however, Little Big Man doesn’t make it as an Indian, or as a white man, either, or as anything else he tries. He looks, listens, remembers, and survives, which is his function. The protagonists in the film are two ideas of civilization: the Indian’s and the white man’s. Custer stages his bloody massacres and is massacred in turn, and we know that the Indians will eventually be destroyed as an organic community and shunted off to reservations. But the film’s movement is circular, and so is its belief about Indians.

Penn has adopted the yarn form for a reason. All the characters who appear in the early stages of the film come back in the later stages, fulfilled. The preacher’s wife returns as a prostitute. The medicine-quack, already lacking an arm, loses a leg (physician, heal thyself). Wild Bill Hickok decays from a has-been to a freak show attraction. Custer fades from glory to madness. Only Old Lodge Skins makes it through to the end not merely intact, but improved.

His survival is reflected in the film’s structure. Most films, especially ones with violence, have their climax at the end. Penn puts his near the center; it is Custer’s massacre of an Indian village, and Little Big Man sees his Indian wife killed and his baby’s head blown off. Penn can control violence as well as any American director (remember “Bonnie and Clyde” and “The Left-Handed Gun”). He does here. The final massacre of Custer and his men is deliberately muted, so it doesn’t distract from Old Lodge Skins’s “death” scene.

But Custer stays dead, and Old Lodge Skins doesn’t quite die (“I was afraid it would turn out this way”). So he leaves the place of death and invites Little Big Man home to have something to eat. Custer’s civilization will eventually win, but Old Lodge Skins’s will prevail. William Faulkner observed in his Nobel Prize speech that man will probably endure — but will he prevail? It’s probably no accident that we don’t smile when Old Lodge Skins explains the difference between Custer and the Human Beings.