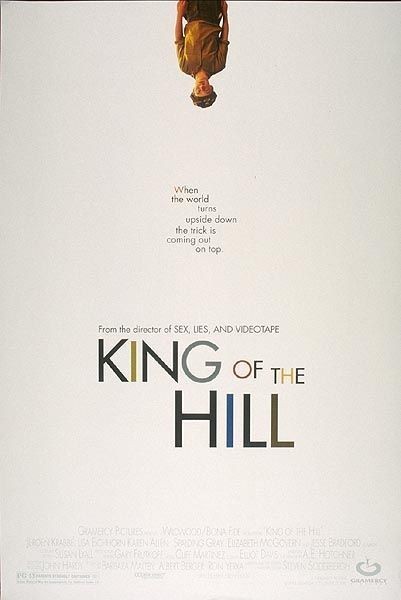

Steven Soderbergh‘s “King of the Hill” is the story of a 12-year-old boy who is left on his own in St. Louis during the Great Depression, and not only survives but thrives, and learns a thing or two. His parents are absent for excellent reasons: His mother is in a TB sanitarium, and his father, a door-to-door salesman, having failed to find much of a market for wickless candles, has left town to travel for a watch company. His younger brother has been shipped away to relatives. That leaves young Aaron (Jesse Bradford) behind in his family’s rooms in the Empire Hotel, a transient hotel not quite nice enough to qualify as a brothel.

As a hero, Jesse has some of the qualities of Huckleberry Finn, David Copperfield or Oliver Twist. He’s plucky, smart, and knows his way around people. It is a sad truth that he could not survive in today’s unkinder world, but in the 1930s he finds it possible to support himself and even attend a prestigious local school, all because of his gift of gab and his genius at creative lying.

“King of the Hill” is based on a 1972 memoir by A.E.

Hotchner, who presumably lived through experiences something like these, and who grew up to be the biographer of Ernest Hemingway and Doris Day, among others, indicating among other things an impressive reach. It’s curious that Steven Soderbergh chose this story for his third film, since it has no apparent connection with his first two: “sex, lies, and videotape,” which was a sensational debut, and “Kafka,” which was a ponderous and uncompelling follow-up. Now, with the kind of material you’d never dream of associating with him, he has made his best film.

Some of the credit goes to Bradford, a young actor who looks thoroughly normal and yet has that rare ability to convince us he is thinking when he seems to be doing nothing. His family has fallen on desperate times. His father (Jeroen Krabbe), an immigrant from Germany, is bedeviled by bill collectors and landlords, and tries everything he can think of to make money. Nothing works. His mother (Lisa Eichhorn) is capable and loving, but too ill to help out, and finally has to go to the sanitarium. After the little brother leaves, his father gives him an earnest lecture, tells him he will send money and be back as soon as possible, and leaves him on his own.

The St. Louis where he must survive seems, here, like a glorious city, one of those places that is tough and devious, where you can break your heart or make your fortune. Young Aaron knows his way around the Empire Hotel, with its bribable bellboys and its semipermanent guests such as the elusive Mr. Mungo (Spalding Gray), who lives across the hallway and occasionally sobers up enough to entertain a prostitute (Elizabeth McGovern), who is slightly less hapless than he is.

The movie follows Aaron’s adventures as he talks his way into a private school, creating out of whole cloth a story about his family. He charms a rich girl and is even invited to her house, but he also survives on the streets, and at one point learns to drive, on the spot, when his father’s car must be hidden from the collection agency.

This material could make many different kinds of movies.

“King of the Hill” could have been a family picture, or a heartwarming TV docudrama, or a comedy. Soderbergh must have seen more deeply into the Hotchner memoir, however, because his movie is not simply about what happens to the kid. It’s about how the kid learns and grows through his experiences. It’s about growing up, not just about having colorful adventures. And despite the absence of Aaron’s family for much of the picture, it’s about the support a family can give – even, if it’s believed in, when it isn’t there.