Philip Seymour Hoffman has a gift for playing quickly embarrassed men who fear rejection. He can convey such vulnerability in some roles that we’re on his side without the script needing to persuade us. We want to finish his sentences, clap him on the back, cheer him up. In other roles, such as “Synecdoche, New York,” he projects enough ego to enforce his will for years on end. There’s an actor for you.

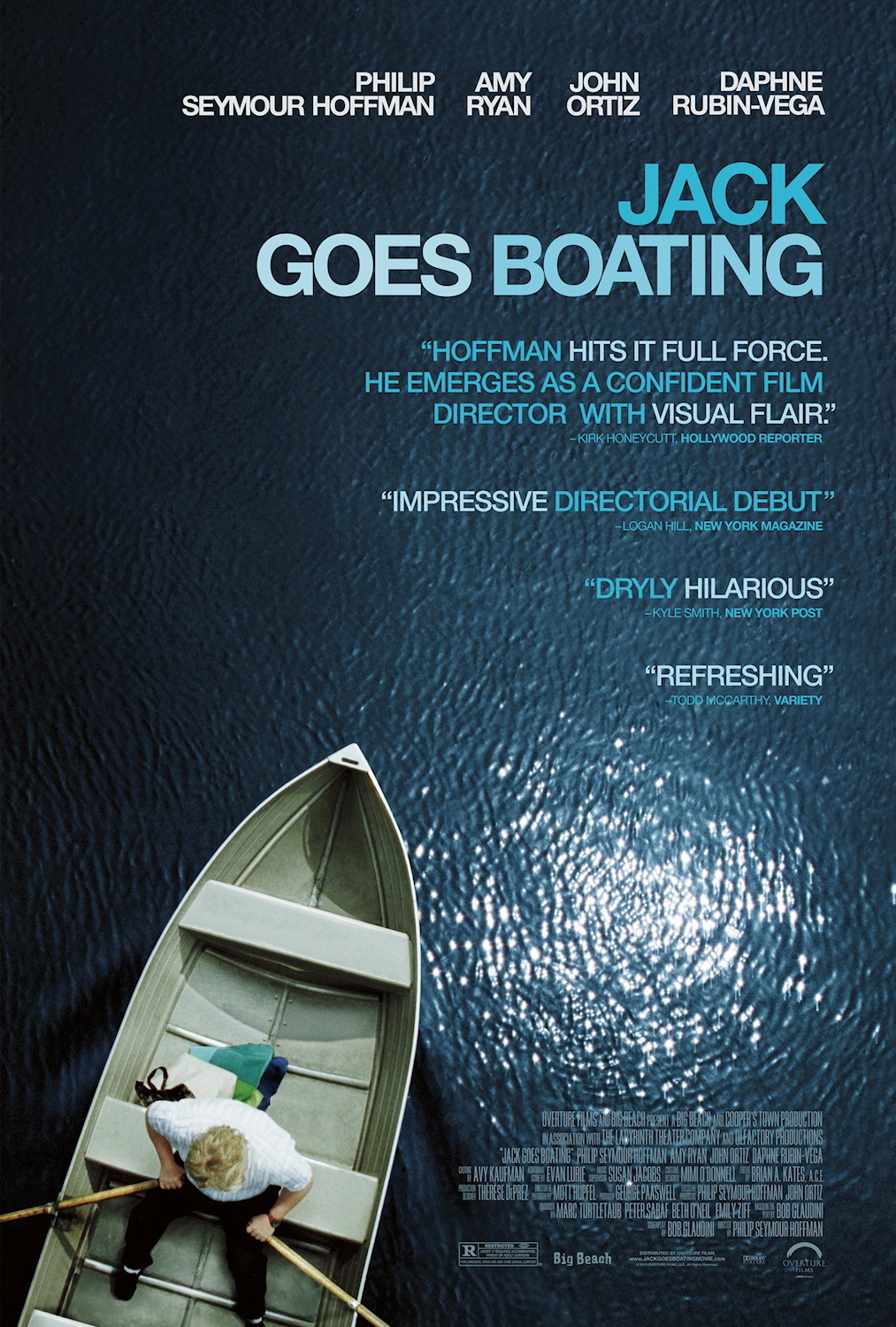

In “Jack Goes Boating,” Hoffman is not only the star but the director. He is merciless in using himself as an actor. His face is often seen in close-up, sweaty, splotchy, red as if he suffers from rosacea. He seems to be perpetually blushing. In life, Hoffman’s skin is perfectly normal; not every actor would stand for this, but vanity is not one of Hoffman’s sins.

In the movie, he plays a limousine driver for a company owned by his uncle, which gives us an idea of his stature in the family. At dawn, he meets for coffee with his best friend, Clyde (John Ortiz), and they sit in a parked limo and regard the unattainable towers of Manhattan. Jack is clueless. Clyde is effortless. Even in their 40s, they have a student-teacher relationship. Clyde is going to teach Jack how to chat up a girl, make himself likable, swim, row a boat, even eventually cook a meal for her — which may be asking for too much.

Clyde is married to Lucy (Daphne Rubin-Vega). She works in a funeral home with Connie (Amy Ryan). Connie is the kind of person who you’d describe as sweet, but terribly shy. Clyde and Lucy decide these two people belong with each other perhaps by default because they appear to belong with nobody else.

This leads into a dinner that reminds me a little of Mike Leigh’s “Abigail’s Party,” in the sense that the wrong people are in the wrong room at the wrong time, and social embarrassment is the main course. The movie is based on an Off-Broadway play by Bob Glaudini, which Hoffman and Ortiz produced and acted in with Rubin-Vega. It has a touch of Leigh and more than a touch of kitchen-sink drama; its stage origins are suggested by the way Clyde lives in a flat where the kitchen, dining area and the living area are essentially one space — that works beautifully when his dinner for Connie goes wrong, as it must.

It’s expected in a four-character play that all four characters will come into play, and they do, in an unexpected way. The interplay between Clyde and Connie is awkward and initially promising, but it’s clear they have a lot of shyness to overcome in catching up to Jack and Lucy. Still, even happy marriages have their secrets.

You can sense the familiarity the actors have with their roles, but there’s not the sense they’ve been this way before. What has traveled this path is the screenplay, which follows a familiar pattern and is essentially redeemed by the meticulous performances. The actors make it new and poignant, and avoid going over the top in the story’s limited psychic and physical space. Even at their highest pitch, the emotions of these characters come from hearts long worn down by the troubles we see.