Maybe my problem was that somehow I got it stuck in my head that “Intersection” was a Thriller. If I’d known it was a Weeper, I wouldn’t have wept, but at least I wouldn’t have been waiting for an hour for someone to pull out an ice pick.

The movie is a belated reminder of one of the unmourned genres of earlier years, the Shaggy Lover Story, in which a doomed romance is told against a backdrop of impending heartbreak. The twist at the end is supposed to send you out of the theater blowing your nose, but the people around me seemed more concerned with clearing their sinuses.

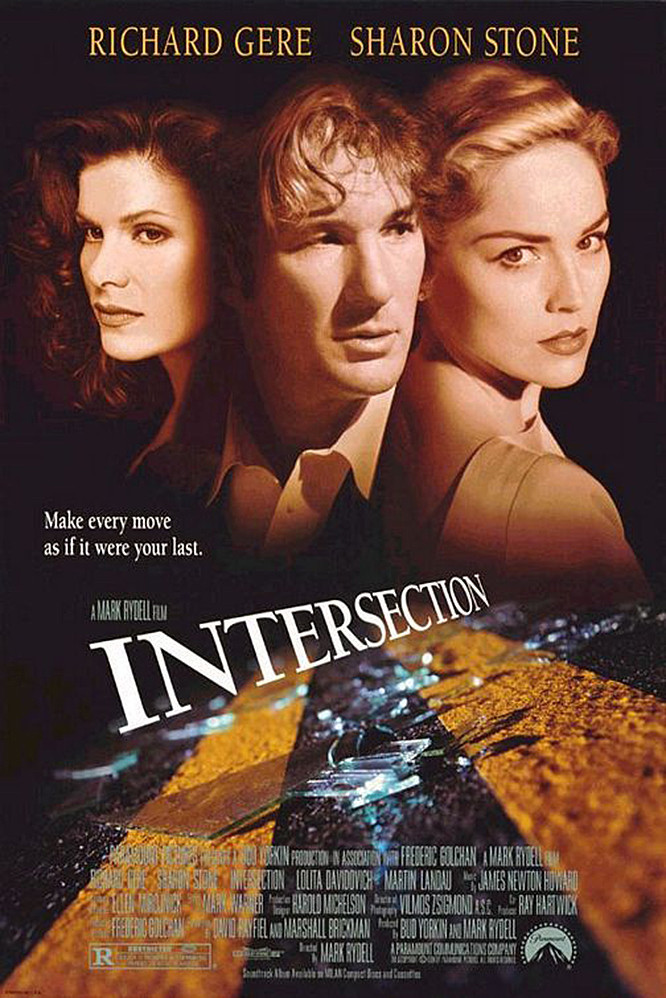

“Intersection” stars Richard Gere as an architect who is torn between two women: his wife, who is cold but uninteresting, and his lover, who is warm but uninteresting. Gere is not interesting either.

The only thing these characters have to talk about are the problems manufactured for them by the screenplay. No other conversations on any other subject amount to more than filler between crises.

Gere and his estranged wife Sally (Sharon Stone) are partners in an architectural firm. Their marriage, seen in laborious flashbacks, is a “business partnership,” he complains, in which she runs the business and he has the ideas. He meets a journalist named Olivia (Lolita Davidovich), falls in love, moves out on his wife and daughter, and begins to talk about the new house he will build for himself and Olivia.

But . . . should he? Is he still attracted to Sally? He doesn’t seem to know. Does he feel guilt about leaving his daughter? Sometimes. Does Olivia understand him? Yes. But, darn it all, things are so complicated! Martin Landau, his associate at work, tells him: “You have a wife and child in one place, a lover in another place . . . that’s just plain messy. Keep everything under one roof. That’s a basic rule of architecture.” I am sure people talk like this somewhere. I don’t want to go there.

I also don’t want to give away the ending of the movie. That means I can’t give away the beginning, either, because the whole movie is one long flashback within which are contained shorter flashbacks, all setting the stage for near-death visions. As nearly as I can tell, only about five minutes of the movie is supposed to take place in the present.

All of these observations pale by comparison to the film’s central problem, which is that director Mark Rydell and writers David Rayfiel and Marshall Brickman have not given us characters of the slightest interest. Stone plays the wife like a woman with a migraine, Davidovich plays the lover like a good sport, and Gere plays the man in the middle as if life would be a lot easier if he hadn’t ever met either woman.

All three people share a strange characteristic common to many Hollywood films: All of their behavior is linked directly to the plot. Unlike the people in European films, they have no lives, no ideas, no questions, no quirks, no real jobs, aside from the plot.

(Precious little architecture or journalism gets performed in this movie.) The movie isn’t even very good at handling ancient staples like marital fights: Gere and Stone have a weirdly off-center, badly timed argument that leads up to the old dependable Packing A Bag And Moving Out Scene (played by him this time). It’s so unconvincing we’re reduced to noticing that after he grabs three unspecified items from a drawer and throws them onto the bed, the drawer is empty. Must be the drawer where he keeps his Packing A Bag clothes.

All this leads up to an O. Henry twist at the end, involving an answering machine, an unsent letter and bittersweet irony. There is a crucial scene between Davidovich and Stone that would have been child’s play for experienced Weeper stars like Joan Crawford or Bette Davis. In “Intersection,” it plays like an afterthought.