1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey orders given it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

–Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot

‘I, Robot” takes place in Chicago circa 2035, a city where spectacular new skyscrapers share the skyline with landmarks like the Sears (but not the Trump) Tower. The tallest of the buildings belongs to U.S. Robotics, and on the floor of its atrium lobby lies the dead body of its chief robot designer, apparently a suicide.

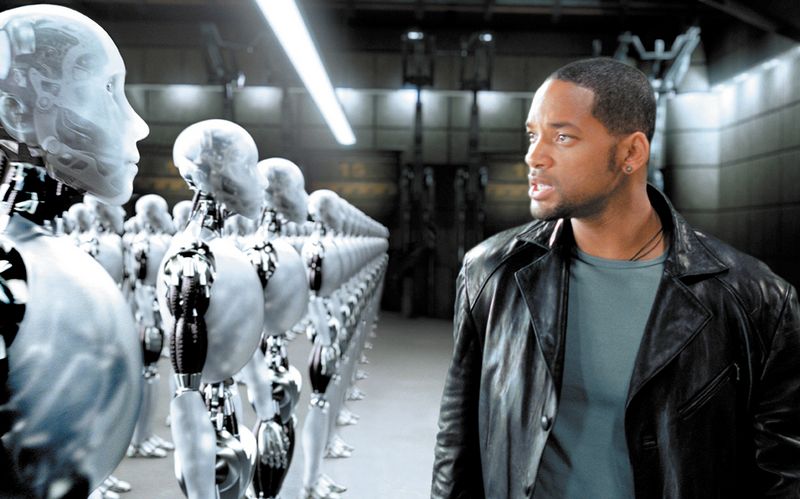

Det. Del Spooner is on the case. Will Smith plays Spooner, a Chicago Police Department detective who doesn’t think it’s suicide. He has a deep-seated mistrust of robots, despite the famous Three Laws of Robotics, which declare above all that a robot must not harm a human being.

The dead man is Dr. Alfred Lanning (James Cromwell), who, we are told, wrote the Three Laws. Every schoolchild knows the laws were set down by the good doctor Isaac Asimov, after a conversation he had on Dec. 23, 1940, with John W. Campbell, the legendary editor of Astounding Science Fiction. It is peculiar that no one in the film knows that, especially since the film is “based on the book by Isaac Asimov.” Would it have killed the filmmakers to credit Asimov?

Asimov’s robot stories were often based on robots that got themselves hopelessly entangled in logical contradictions involving the laws. According to the invaluable Wikipedia encyclopedia on the Web, Harlan Ellison and Asimov collaborated in the 1970s on an “I, Robot” screenplay, which, the good doctor said, would produce “the first really adult, complex, worthwhile science fiction movie ever made.”

While that does not speak highly for “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968), it is certain that the screenplay for this film, by Jeff Vintar and Akiva Goldsman, is not adult, complex or worthwhile, although it is indeed science fiction. The director is Alex Proyas, whose great “Dark City” (1998) was also about a hero trying to make sense of the deceptive natures of the beings around him.

The movie makes Spooner into another one of those movie cops who insults the powerful, races recklessly around town, gets his badge pulled by his captain, solves the crime and survives incredible physical adventures. In many of these exploits he is accompanied by Dr. Susan Calvin (Bridget Moynahan), whose job at U.S. Robotics is “to make the robots seem more human.”

At this she is not very successful. The movie’s robots are curiously uninvolving as individuals, and when seen by the hundreds or thousands look like shiny chromium ants. True, a robot need not have much of a personality, but there is one robot, named Sonny and voiced by Alan Tudyk, who is more advanced than the standard robot, more “human,” and capable of questions like “What am I?” — a question many movie characters might profitably ask themselves.

If Sonny doesn’t have real feelings, he comes as close to them as any of the humans in the movie. Both Spooner and Calvin are kept in motion so relentlessly that their human sides get overlooked, except for a touching story Spooner tells about how a little girl dies because a robot was too logical. Sonny doesn’t seem as “human” as, say, Andrew, the robot played by Robin Williams in “Bicentennial Man” (1999), based on a robot story by Asimov and Robert Silverberg. But his voice has a certain poignancy, and suggests some the chilly chumminess of HAL 9000.

The plot I will not detail, except to note that you already know from the ads that the robots are up to no good, and Spooner could write a lot of tickets for Three Laws violations.

The plot is simple-minded and disappointing, and the chase and action scenes are pretty much routine for movies in the sci-fi CGI genre. The robots never seem to have the heft and weight of actual metallic machines, and make boring villains.

Dr. Susan Calvin is one of those handy movie characters who knows all the secrets, can get through all the doors, can solve all the problems and helps Spooner move almost at will through the Robotics skyscraper, which seems curiously ill-guarded. When they team up against the eventual villain, it’s an obvious ploy to create yet another space where characters can fall for hundreds of feet and somehow save themselves.

As for the robots, they function like the giant insects in “Starship Troopers,” as video game targets. You can’t even be mad at them, since they’re only programs. Although, come to think of it, you can be mad at programs; Microsoft Word has inspired me to rage far beyond anything these robots engender.