[EDITOR’S NOTE: This review contains spoilers.]

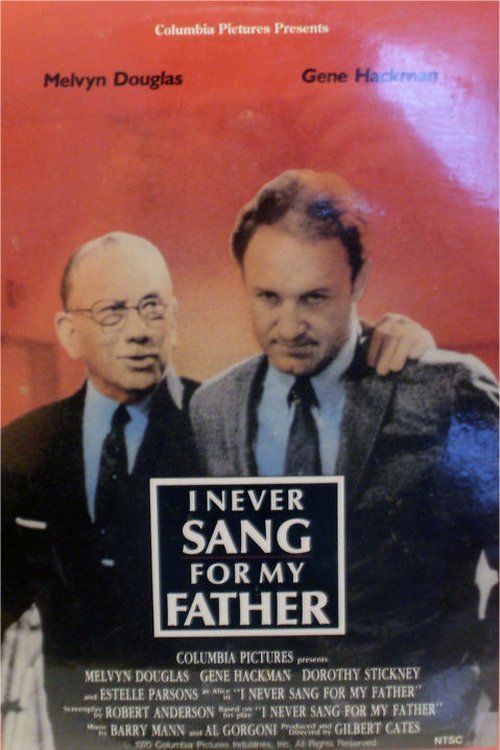

At the beginning and again at the end of “I Never Sang for My Father,” we see a grainy snapshot of an old man and a middle-aged man, arms thrown about each other’s shoulders, peering uncertainly into the camera as if they’re not quite sure what drew them out into the sunshine to pose this day. And we hear Gene Hackman’s voice: “Death ends a life. But it does not end a relationship.”

This film takes that simple fact and uses it to make a poignant and ultimately tragic statement about parents and children, life and death, and all the words that go unspoken. The man is played by Melvyn Douglas, and Hackman plays his son, and the film is about the fierce love they bear for each other, and about their inability to communicate that love, or very much of anything else.

The story takes place at a time when the old man’s life is ending, but he won’t admit it, and when the younger man’s life is about to permit a new beginning. The old man is eighty-one, and a long time ago he was the mayor and the school board president — one of the town’s most important citizens. But now he has largely been forgotten, left to live a comfortable life in the rambling old family home. He lives there with his wife and his memories, and a fierce possessiveness for his son.

What he wants from the son is a show of devotion. He doesn’t communicate with him; indeed, he spends a lot of time falling asleep in front of the television set. But he wants him there, almost as a hostage, because he has a hunger for affection left over from his own neglected childhood. The son tries to go through the motions. But his own wife died a year ago, and now, at forty-four, he has decided to marry a woman doctor who lives in California. This will mean leaving the hometown, and that would be heresy to his father.

The situation becomes urgent when the old man’s wife dies. He seems to accept the death as an inconvenience, transferring his grief to memories of his own mother’s death half a century before. But his dependence upon his son becomes almost total. His daughter (Estelle Parsons) comes home for the funeral; in a fit of rage, the old man had banished her for marrying a Jew. Now she explains to Hackman, with an objectivity that sounds cruel but springs from love, that an arrangement is going to have to be made about their father. He can’t live in the big house by himself.

The trouble is, his pride makes him refuse to hire the housekeeper he could easily afford. He expects his son to watch over him. And Hackman has not gathered the courage to reveal his marriage plans. He goes to look at a couple of old people’s homes, but he finds them depressing and he knows his father would never, ever, go to one. So there you have the son’s dilemma. The father should not live alone. A nursing home seems impossible.

For a moment, the children consider gaining power of attorney and insisting on a housekeeper. But then, in a scene of remarkable emotional impact, the son watches as his father finally breaks down and reveals his grief, and the son invites him to come and live in California. But that, of course, is also unacceptable to the old man, whose pride will not allow him to admit that others could make his decisions, and whose stubbornness makes him insist on having everything his way, no matter what.

These bare bones of plot hardly give any hint of the power of this film. I’ve suggested something of what it’s about, but almost nothing about the way the writing, the direction, and the performances come together to create one of the most unforgettably human films I can remember.

Robert Anderson’s screenplay is from his autobiographical play, and it rings with truth. His dialogue is direct and revealing, without the “literary” touches or sophistication that could have sabotaged the characters. Eugene O'Neill was writing a different kind of dialogue for different purposes in ‘Long Day’s Journey Into Night,’ a somewhat similar work that comes to mind. But for Anderson’s story, which depends on everyday realism and would find symbolism dangerous, the unadorned dialogue is essential.

Gilbert Cates’s direction also respects the fact that this is a movie not about visual style or any other fashionably cinematic selfconsciousness. With the exception of an inappropriate song which sneaks onto the sound track near the film’s beginning, Cates has directed solely to get those magnificent performances onto the screen as movingly as possible. Much of the film is just between the two of them and the characters seem to work so well because Douglas and Hackman respond to each other in every shot; the effect is not of acting, but as if the story were happening right now while we see it.

The film tells us that death ends a life, but not a relationship. That’s true of all close and deep human relationships; when one person dies, the other continues long afterwards to wonder what could have been said between them, but wasn’t.

“I Never Sang for My Father” has the courage to remain open-ended; the father dies, but the problems between father and son remain unresolved. That is really more tragic than the fact of death, because death is natural, but human nature cries out that parents and children should understand each other.