When Officer Josephine (Nellie Munamonga) calls Mr. Banda (Henry B.J. Phiri) in an early scene of Rungano Nyoni’s “I Am Not A Witch,” she interrupts him taking a bath. The government official’s phone plays a goofy-sounding classical music ringtone, which we will hear several more times at equally inopportune moments during the film. Officer Josephine explains to Mr. Banda that someone at her police station has been accused of being a witch. Nyoni shoots Banda’s lackadaisical reaction entirely from behind him as he lounges in the tub; it sounds as if this is a regular occurrence because Banda’s responses completely lack surprise. That is, until Officer Josephine tells him that the accused refuses to confirm or deny the witchcraft charge.

At no point does the arrested young girl, Shula (Maggie Mulubwa) utter the film’s title, nor is the viewer ever fully sure if her unwillingness to answer constitutes an admission. What we do know is that there are “witches” in this Zambian village and that, like in Salem, their convictions stem more from the fear, jealousy, or wrath of their accusers than from any evidence of black magic. For example, one of the villagers tells Officer Josephine that Shula chopped one of his arms off with an ax, flailing both of his arms wildly as he tells the story. The original complainant screams witchcraft because she dropped her bucket of water when Shula suddenly startled her.

Guilt or innocence doesn’t matter, as Banda is happy to have another witch to add to his coven. He’s even happier when he discovers his latest addition is about eight or nine and willing to go without protest. “New witch in town. Fresh and young!” sings Banda. His witches, many of whom are older women, serve as an uneasy combination of chain gang, field hands and even tourist attractions. The film’s opening scene is a rather savage mockery of the Western world’s ignorance of different cultures. Two visiting Brits take pictures of the women, each of whom is tethered to an enormous spool of ribbon that constricts the distance they may travel. Their tour guide explains that the ribbon keeps them from flying away. “They can even fly as far as the U.K. where they can kill you!” he tells them. The picture-takers happily snap away, not noticing that what they’re surveying looks at best like a prison and at worst, like something far more sinister and deadly.

“I Am Not A Witch” works in this vein of satire until its haunting ending, and Nyoni does an excellent job of keeping an absurd tone while losing none of the gravity of the situation. She accomplishes this by never reducing her subjects’ humanity. There really are witch camps with people who, like Nyori’s women, have been railroaded into incarceration. The director’s imagined additions to this reality, such as the ribbons, are all elements that patriarchal society would consider blatantly feminine symbols. The radical act of cutting the ribbon, a choice given to Shula on the first day of her capture, carries a stigma that shrouds the fear of female agency within the wolf’s clothing of a cultural fear. “Do you want to be a witch or a goat?” Shula is asked. The goat would be “killed and eaten within a day,” her elders tell her. But a witch would survive, which would carry far less shame and a false sense of power.

The witches seem to know they’re being played. “We’re soldiers for the government and we’re used to it,” they sing. “We’re used to it and we don’t get tired.” The elders seek to protect Shula as best they can, imploring her to listen through a homemade contraption so that she may hear the distant voices of schoolchildren learning nearby. They also attempt to shield her from the harder labor they endure, shaming Banda into keeping her off the fields. As a result, the bumbling yet dangerous Banda uses Shula as a prop of sorts, bringing her on TV, using her “powers” to settle criminal cases and to placate White and African business people who pay for Banda’s group to make rain for their crops.

Nyoni treats satire and drama like a teeter-totter—there’s always the motion of a temporary imbalance that levels out at just the right moment. One also gets the feeling that we’re occasionally meant to experience this world through the eyes of its child protagonist. Nyoni represents this in several scenes where ugliness happens offscreen or is revealed in a line that seems throwaway but is actually rife with detail. In an example of the former, the camera stays put while characters exit the screen, leaving us only with the sound of argument and struggle. In an example of the latter, a man brings one of the women back to the camp and another camp member throws rocks at him while revealing that he is the reason she’s been sentenced as a witch.

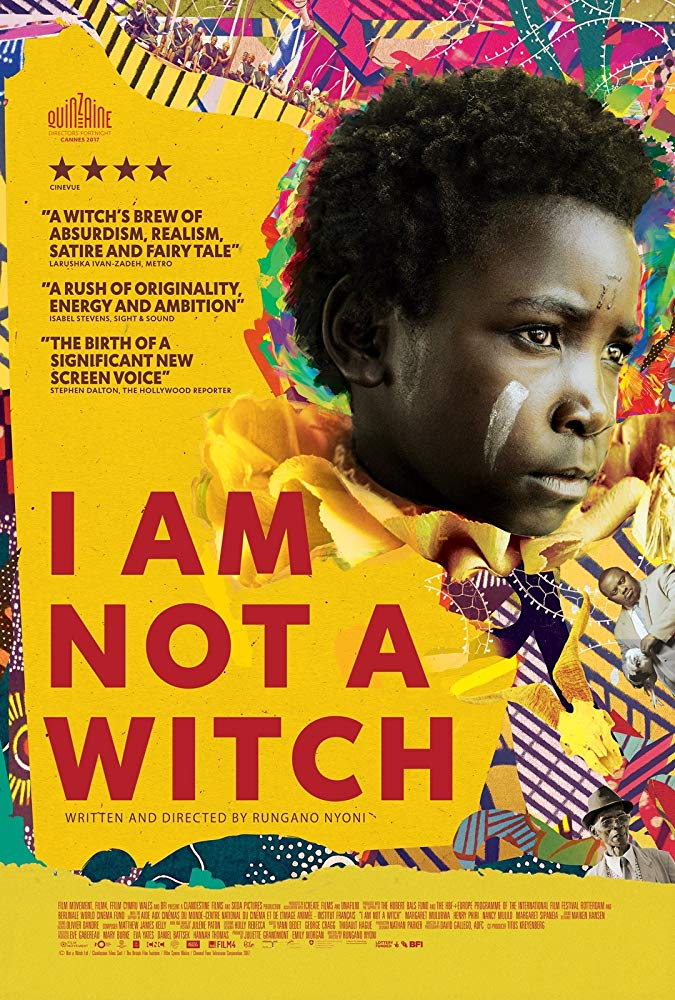

At the center of “I Am Not A Witch” is Maggie Mulubwa, who says very little yet manages to convey multitudes with her face and her eyes. This is a feat made more impressive by the fact that Nyoni gives us absolutely no backstory on Shula. Like her, we are thrust into this world of carefully calibrated insanity and left to fend for ourselves. The elder who christens Mulubwa’s unnamed character “Shula” does so because the word means “uprooted.” Shula has indeed been uprooted; she’s been displaced by society and left to wander as a lost soul. But like many lost souls, her presence is strongly felt and will never be forgotten.