Two little creatures are perched on my shoulders, one whispering into each ear. One carries a pitchfork. The other has gossamer wings.

They are dictating this review of “The Hudsucker Proxy.” Angel: This is the best-looking movie I’ve seen in years, a feast for the eyes and the imagination. The art direction and set design are breathtaking, re-creating the world of 1930s screwball comedy in which towering skyscrapers and vast boardrooms were the playing fields for the ambitions of corrupt executives, ambitious kids, unsung geniuses, and lady newspaper reporters with nails as sharp as their wisecracks.

Devil: But the problem with the movie is that it’s all surface and no substance. Not even the slightest attempt is made to suggest that the film takes its own story seriously. Everything is style. The performances seem deliberately angled as satire.

Angel: But those performances are right on target. Tim Robbins stars, as a mailroom clerk who finds himself thrust into the presidency of the giant Hudsucker Corporation. Paul Newman is the gray eminence behind the scenes, who engineers Robbins’ ascendancy because he believes the kid is hopelessly incompetent, and will drive the stock price down – just what Newman desires. And Jennifer Jason Leigh has been studying Rosalind Russell in “His Girl Friday,” and has the part down perfect: The hard-bitten, fast-talking girl reporter who sits on your desk, lights a cigarette, and lays down the law. Devil: So what? Was there anyone in this movie to really care about? And did the screwball aspects of the story ever take hold? Screwball comedy needs a certain looseness, an anarchic spirit that’s alien to the meticulous productions of the Coen Brothers, Joel and Ethan, who in this film as in their others (“Blood Simple,” “Raising Arizona,” “Miller's Crossing,” “Barton Fink“) seem to be so much in love with old movies that they shape their own ideas into the forms of films made before they were born.

Angel: Which brings me back to why I want to see the movie again. There is a grandness to the very conception of “The Hudsucker Proxy,” which sets the stage in the opening sequence, as an executive jumps out of a skyscraper and the camera proceeds him in a headlong falls down what looks like a couple of hundred stories of terrifying free-fall, before . . . but you know the scene I mean. It was exhilarating.

Devil: But to what purpose other than pure style? And is there a glitch between the movie’s look and style, which are clearly 1930s Art Deco, and its claim to be set in the 1950s? Angel: Who really cares about stuff like that? Putting it in the 1950s allowed the Coens to have a lot of fun with the brainstorm of the Robbins character, who invents the hula hoop and makes untold billions for Hudsucker.

And the hula hoop, in turn, provides an excuse for a montage showing hoopery sweeping across America – a filmmaking device which the Coens somehow are able to exploit and kid at the same time.

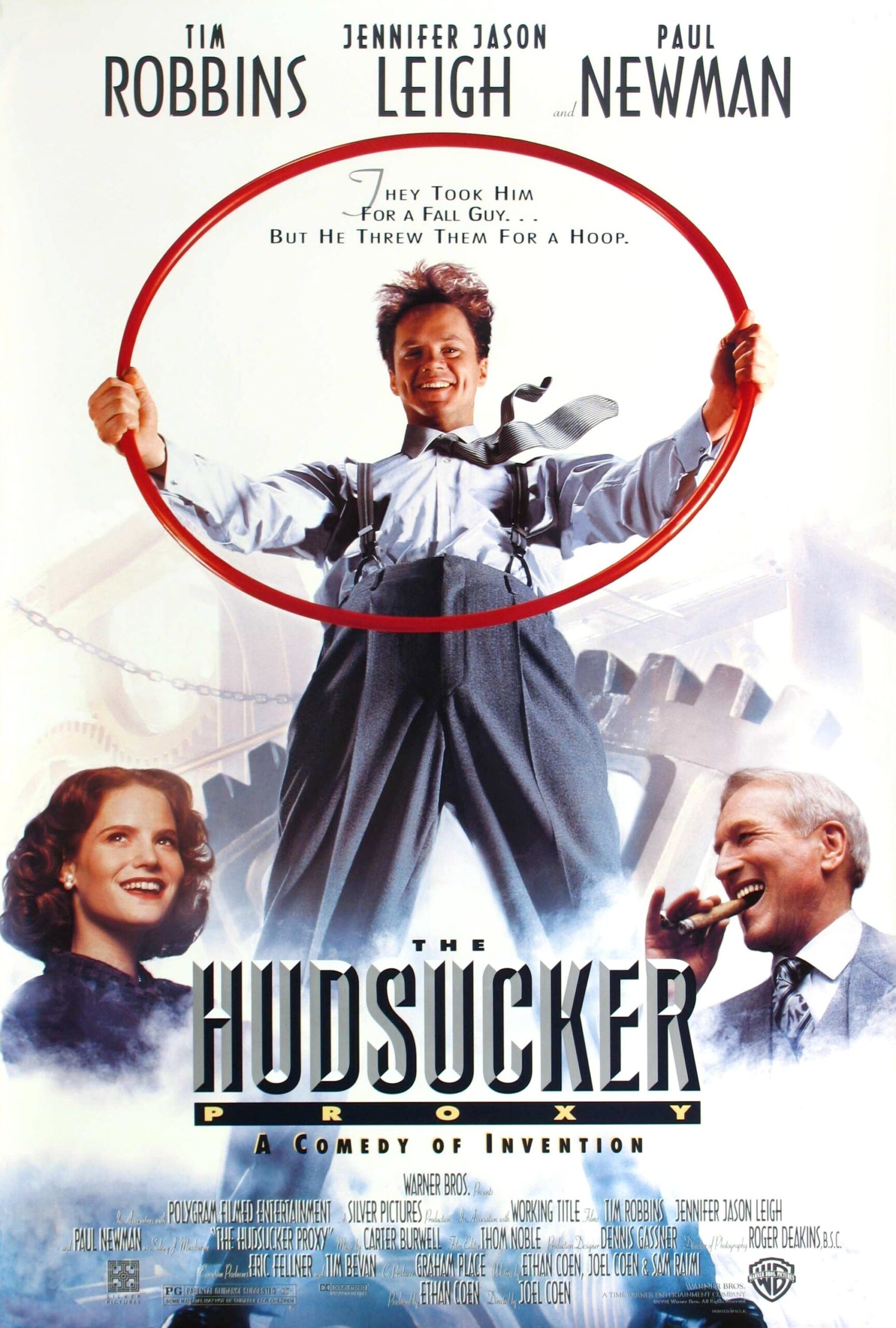

Devil: Wouldn’t it have been a little more fun, though, if the hula hoop came as a surprise? The ads and the poster for the Coens movie shows Robbins holding a big hula hoop, so walking into the theater, you know the secret. It’s typical of their approach: They obviously think their plot is unimportant except as a clothesline for the visuals. And wasn’t there something dead at the heart of all of this? A kind of chill in the air? A feeling that the movie was more thought than art, more calculated than inspired? Doesn’t the viewer spend more time admiring the sights on the screen than caring about them? Isn’t there something wrong when you walk out of a movie humming the sets? Angel: That’s the tired old rap against the Coens, that they’re all technique and no heart. How many movies do have heart these days? Not many. Most movies recycle tired old formulas; even a so-called Generation X rebel picture like “Reality Bites” is just a retread of a 1930s romantic comedy that could have played on the same double bill with whatever inspired “The Hudsucker Proxy.” One good reason to go to the movies is to feast the eyes, even if the brain remains unchallenged. And “Hudsucker” is a pleasure to regard.

Devil: Unless you want something more from a movie.

The debate goes on. Just before they vaporized into thin air, the angel advised me to give “The Hudsucker Proxy” four stars, and the Devil, whispering that the Coens are talented but need to be prodded to go beyond their technical mastery, wickedly advised me to cut them off with zero. Having weighed all their advice, I have taken a middle position.