As the opening credits roll, we see the man prepare for his day in close-up. He wets his hair and slicks it back with styling product. He ties his tie, does up his pants and puts on a suit coat, making sure the handkerchief in the breast pocket is nice and square. He knots the laces of his leather shoes, and after all of this, he’s ready to face the day. Then director Thomas Wirthensohn shows us the entirety of the man against his surroundings. This man, who looks quite dapper after the process, has been going through his morning routine in a public restroom.

His name is Mark Reay, a man in his early 50s who has been homeless for five or maybe six years. He isn’t certain about the time frame. Who could blame him?

He sleeps in a tiny alcove on the roof of an apartment building in Manhattan where one of his friends lives. The friend, who gave Reay a key to the building so he could look after the apartment whenever the friend is on vacation, doesn’t know this, and whenever Reay walks into that building (or another one across the street where he has a secondary rooftop shelter), he has to make sure no one sees him climb the stairs to the roof. He seems less worried about some stranger calling the police than he is about the friend seeing him. “It would be awkward,” he says.

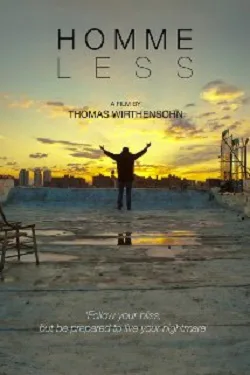

Reay is the subject of “Homme Less,” a documentary that follows him over the course of two years of his day-to-day life. He spends his days walking the streets, taking photographs of pretty women dressed with a certain sense of fashion for a “street styles” section of a magazine.

That’s one of his gigs. The photography work becomes a little more substantial during New York Fashion Week, when Reay gets to go backstage and attend red carpet events at various fashion shows throughout the city. He dabbles in acting, too, although his credits are mostly for background work. It’s enough that he can use the Actors’ Equity Association’s credit union (the only bank that will accept his business) and receive a discount on health insurance through his membership in the Screen Actors Guild. At one point, Reay was a model, but he didn’t find the work intellectually stimulating enough.

This man doesn’t fit the model of our traditional perception of a homeless person. Wirthensohn shows us people who do, as Reay passes them in the street and during a montage that juxtaposes middle-class folks going about their day with the poverty-stricken digging through garbage and begging for money. It’s difficult to determine if Wirthensohn is equating Reay with the latter group, if the director is slightly jabbing his subject by the comparison, or if he’s trying to make us consider Reay as existing in some unique, undefined socioeconomic status between the two.

Reay pretty much admits he’s homeless by choice, as a way to save on the expense of renting an apartment. After all, he needs the little money he earns in order to do the work he wants to do, which often includes networking at bars until 2 o’clock in the morning. He could get a “normal” job if he wanted, but he doesn’t want to. Reay speaks directly to the camera, telling the audience that we can feel free to come up to that roof and tell him to get a regular job. “Kick my ass,” as he puts it, and we can’t tell if he means that literally or figuratively.

In other words, this isn’t some sob story. Reay doesn’t believe he or his situation deserve much pity or sympathy. We know this because he looks directly into the camera to tell us as much (He later tells us that we can feel free to send some money his way, since his living situation is going to be severely compromised with existence of this documentary). He’s living la vie boheme, although there’s no romance to it when he shows us his water jug, which is now filled with urine (It is, admittedly, economical).

The film is, though, a fascinating account of a man who plays a role in order to hide the reality of his life. We’re often told to dress for the job we want, but Reay is dressing for the life he must appear to have if he’s ever going to get the job he wants. It seems to be working, if only to an extent. He gets work, as sparsely paid as it is. He’s able to flirt and canoodle with aspiring models, although he’s certain he’s incapable of giving or receiving love.

Part of Reay’s “job” is to make himself appear successful, but he also seems to be content with or, at least, accustomed to his situation. During a couple of late-night confessionals on that rooftop, though, he admits he has doubts about his career ever going anywhere and about his worth as a person. For a man who lies daily about his lot in life, Reay is surprisingly, starkly honest about himself.

There are no major revelations about why Reay lives the way he does—no tragic story or significant setback in his past. Wirthensohn flat-out asks him at one point in “Homme Less,” and Reay simply says that things didn’t quite work out the way he expected. We can relate to that sentiment. We can also, sort of admire Reay’s persistence in chasing his dream, even as we wonder if we would have the willpower or patience to live as he does and question his judgment in taking the pursuit to such an extreme.