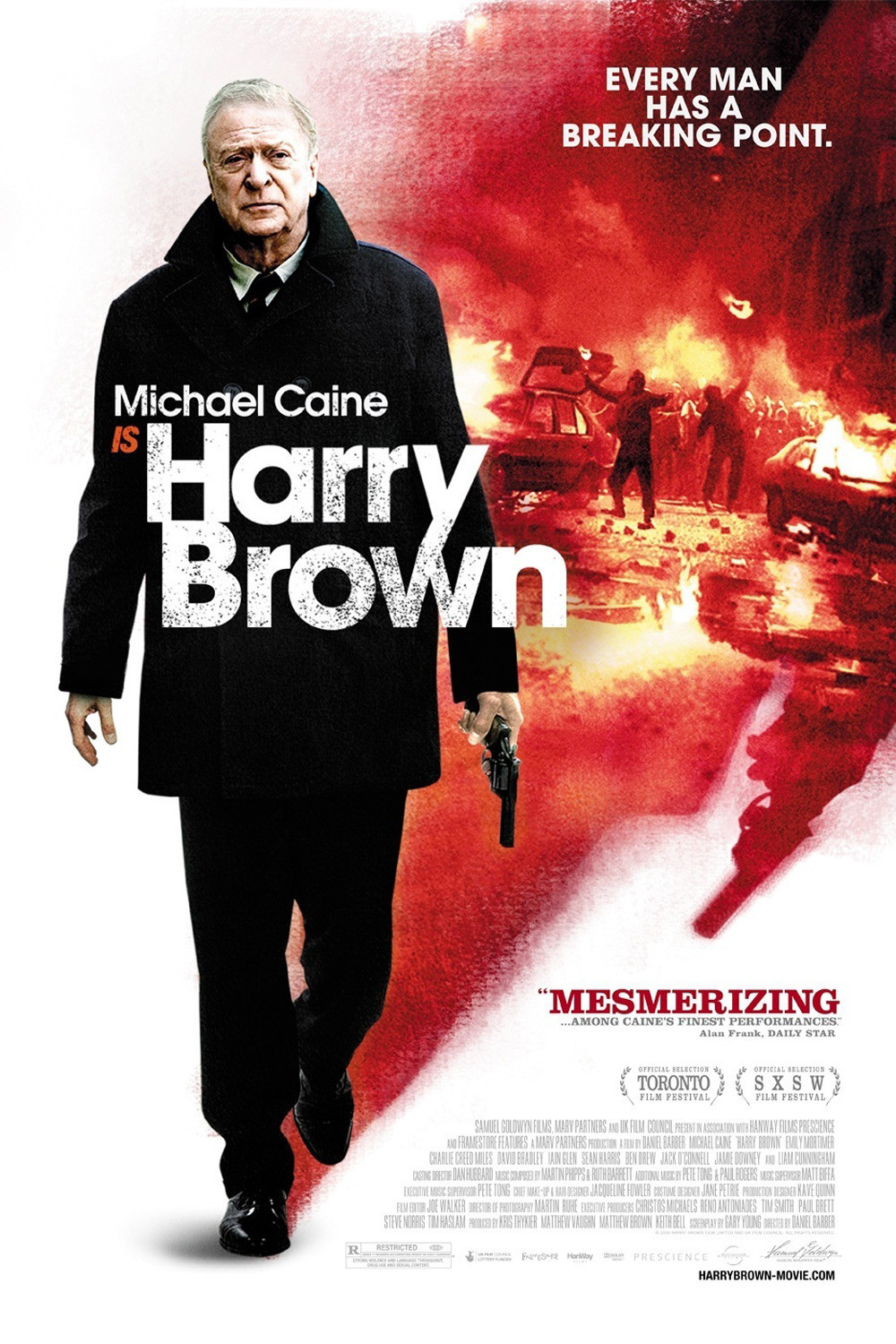

“Harry Brown” is a revenge thriller poised somewhere between “Death Wish” and “Gran Torino.” All three depend on the ability of an older actor to convince us that he’s still capable of violence, and all three spend a great deal of time alone with their characters, whose faces must reflect their inner feelings. Charles Bronson, Clint Eastwood, Michael Caine: Those are faces sculpted by time.

Caine plays an old man with a dying wife. He lives in a London housing estate used by a drug gang as its own turf. Pedestrians are terrorized and beaten, drugs are openly sold, there are some areas understood as no-go. From his high window, Harry hears a car alarm and looks down to see the car’s owner come out and be beaten by thugs. This is the daily reality.

Caine is a subtle actor who builds characters from the inside out. His voice has become so familiar over the years, that it’s an old friend. In this film, he begins as a lonely, sad geezer, and gradually an earlier persona emerges, that of a British marine who served in Northern Ireland. All of that has been put in a box and locked away, he says, and thinks.

There’s a pub on the estate, quiet in the daytime, where he and his old friend Leonard (David Bradley) meet for studious games of chess. The thugs have been shoving dog mess through Leonard’s mail slot. His life is miserable. He shows Harry a gun. One day when the gang pushes burning newspapers through the slot, he goes to confront them in an underpass they control. Frampton (Emily Mortimer), a young police inspector, comes to tell Harry that Leonard has been killed.

The inspector is human, and sympathetic. Harry tells her the police have no control over the area, and she cannot disagree. Her superior officer has his own notions. And then the film takes the turn that we expect, and in the process, takes on aspects of a more conventional police procedural.

What Caine is successful at, however, is always remaining in character. Like Eastwood, and unlike Bronson, he is always his age, always in the same capable but aged body. The best scene in the movie involves his visit to the flat of a drug dealer, where Harry plans to buy a gun. There’s a semi-comatose girl on the sofa. The situation is fraught. How Harry handles it depends not on strength but on experience and insight. He carefully conceals his cards.

The police investigation is misdirected for political motives. Frampton has an excellent notion of who may be responsible for the killings of neighborhood hoods, but cannot get a hearing. It would not do for a geezer to outdo the police. Vigilante activity is of course not the answer to urban crime, but what is? In Chicago, Daley floods many area with cops, and shootings continue nearby. It’s all fueled by drugs and drug money, of course. You know, one of the areas where I think Libertarians may be right is about the legalization of drugs. There would be less of them with no profit motive for their sale. Less money for guns. Fewer innocent bystanders would die. Who knows?

This movie plays better than perhaps it should. Directed as a debut by Daniel Barber, it places story and character above manufactured “thrills” and works better. We are all so desperately weary of CGI that replaces drama. With movies like this, humans creep back into crime stories. There is a clear thread connecting this Michael Caine and the Caine of “The Ipcress File.” You may not be able to see it, but it’s there.