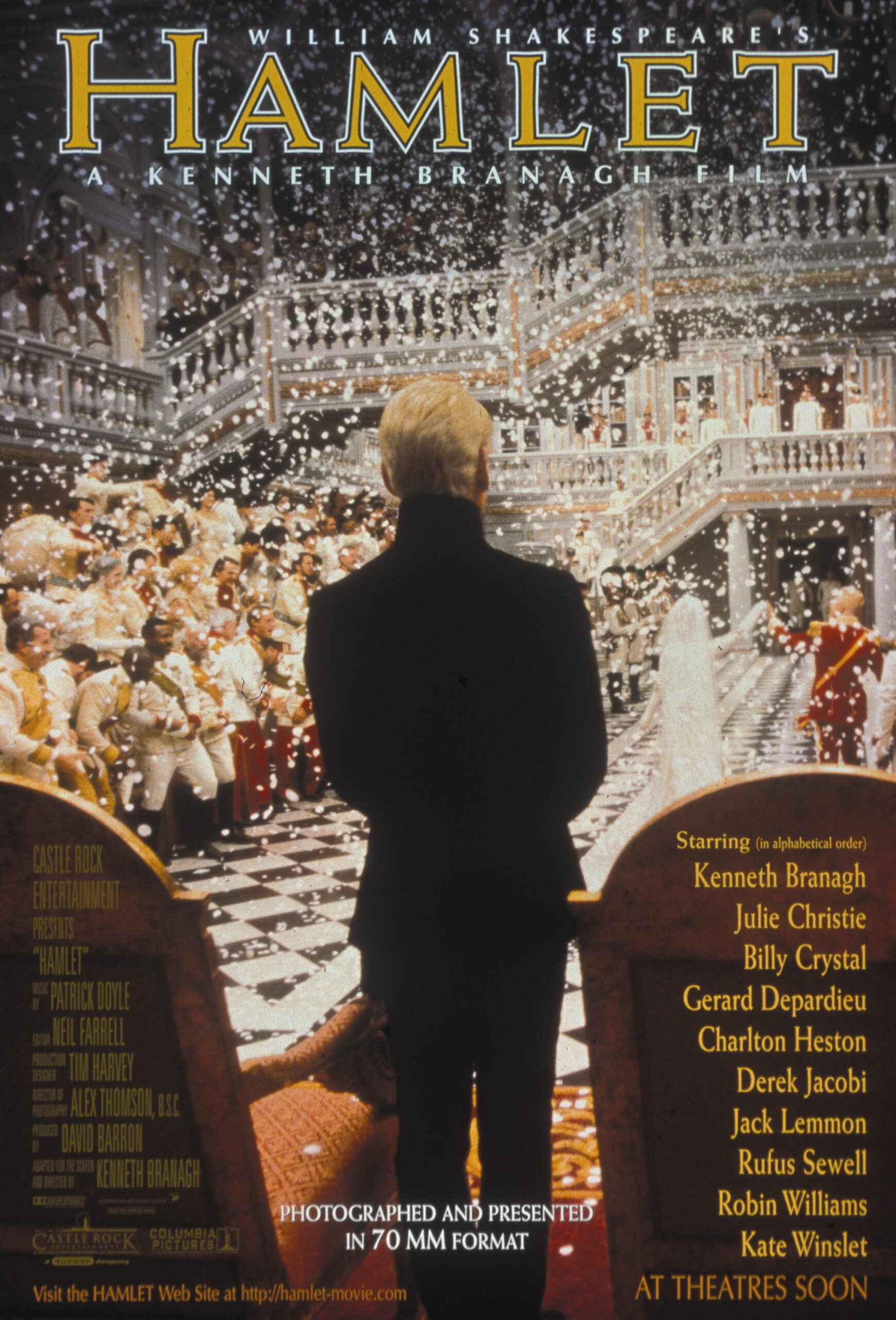

There is early in Kenneth Branagh’s “Hamlet” a wedding celebration, the Danish court rejoicing at the union of Claudius and Gertrude. The camera watches, and then pans to the right, to reveal the solitary figure of Hamlet, clad in black. It always creates a little shock in the movies when the foreground is unexpectedly occupied. We realize the subject of the scene is not the wedding, but Hamlet’s experience of it. And we enjoy Branagh’s visual showmanship: In all of his films, he reveals his joy in theatrical gestures.

His “Hamlet” is long but not slow, deep but not difficult, and it vibrates with the relief of actors who have great things to say, and the right ways to say them. And in the 70-mm. version, it has a visual clarity that is breathtaking. It is the first uncut film version of Shakespeare’s most challenging tragedy, the first 70-mm. film since “Far and Away” in 1992, and at 238 minutes the second-longest major Hollywood production (one minute shorter than “Cleopatra”). Branagh’s Hamlet lacks the narcissistic intensity of Laurence Olivier’s (in the 1948 Academy Award winner), but the film as a whole is better, placing Hamlet in the larger context of royal politics, and making him less a subject for pity.

The story provides a melodramatic stage for inner agonies. Hamlet (Branagh), the prince of Denmark, mourns the untimely death of his father. His mother, Gertrude, rushes with unseemly speed into marriage with Claudius, her husband’s brother. Something is rotten in the state of Denmark. And then the ghost of Hamlet’s father appears and says he was poisoned by Claudius What must Hamlet do? He desires the death of Claudius but lacks the impulse to act out. He despises himself for his passivity. In tormenting himself he drives his mother to despair, kills Polonius by accident, speeds the kingdom toward chaos and his love, Ophelia, toward madness.

What is intriguing about “Hamlet” is the ambiguity of everyone’s motives. Tom Stoppard’s “Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” famously filtered all the action through the eyes of Hamlet’s treacherous school friends. But how does it all look to Gertrude? To Claudius? To the heartbroken Ophelia? The great benefit of this full-length version is that these other characters become more understandable.

The role of Claudius (Derek Jacobi) is especially enriched: In shorter versions, he is the scowling usurper who functions only as villain. Here, with lines and scenes restored, he seems more balanced and powerful. He might have made a plausible king of Denmark, had things turned out differently. Yes, he killed his brother, but regicide was not unknown in medieval times, and perhaps the old king was ripe for replacement; this production shows Gertrude (Julie Christie) as lustfully in love with Claudius. By restoring the original scope of Claudius’ role, Branagh emphasizes court and political intrigue instead of enclosing the material in a Freudian hothouse.

The movie’s very sets emphasize the role of the throne as the center of the kingdom. Branagh uses costumes to suggest the 19th century, and shoots his exteriors at Blenheim Castle, seat of the duke of Marlborough and Winston Churchill’s childhood home. The interior sets, designed by Tim Harvey and Desmond Crowe, feature a throne room surrounded by mirrored walls, overlooked by a gallery and divided by an elevated walkway. The set puts much of the action onstage (members of the court are constantly observing) and allows for intrigue (some of the mirrors are two-way, and lead to concealed chambers and corridors).

In this very public arena Hamlet agonizes, and is observed. Branagh uses rapid cuts to show others reacting to his words and meanings. And he finds new ways to stage familiar scenes, renewing the material. Hamlet’s most famous soliloquy (“To be or not to be . . .”) is delivered into a mirror, so that his own indecision is thrust back at him. When he torments Ophelia, a most private moment, we spy on them from the other side of a two-way mirror; he crushes her cheek against the glass and her frightened breath clouds it. When he comes upon Claudius at his prayers, and can kill him, many productions imagine Hamlet lurking behind a pillar in a chapel. Branagh is more intimate, showing a dagger blade insinuating itself through the mesh of a confessional.

One of the surprises of this uncut “Hamlet” is the crucial role of the play within the play. Many productions reduce the visiting troupe of actors to walk-ons; they provide a hook for Hamlet’s advice to the players, and merely suggest the performance that Hamlet hopes will startle Claudius into betraying himself. Here, with Charlton Heston magnificently assured as the Player King, we listen to the actual lines of his play (which shorter versions often relegate to dumb-show at the back of the stage). We see how ingeniously and cleverly they tweak the conscience of the king, and we see Claudius’ pained reactions. The episode becomes a turning point; Claudius realizes that Hamlet is on to him.

As for Hamlet, Branagh (like Mel Gibson in the 1991 film) has no interest in playing him as an apologetic mope. Branagh is an actor of exuberant physical gifts and energy (when the time comes, his King Lear will bound about the heath). Consider the scene beginning “Oh, what a rogue and peasant knave am I . . .,” in which Hamlet bitterly regrets his inaction. The lines are delivered not in bewilderment but in mounting anger, and it is to Branagh’s credit that he pulls out all the stops; a quieter Hamlet would make a tamer “Hamlet.” Kate Winslet is touchingly vulnerable as Ophelia, red-nosed and snuffling, her world crumbling about her. Richard Briers makes Polonius not so much a foolish old man as an adviser out of his depth. Of the familiar faces, the surprise is Heston: How many great performances have we lost while he visited the Planet of the Apes? Billy Crystal is a surprise, but effective, as the gravedigger. But Robin Williams, Jack Lemmon and Gerard Depardieu are distractions, their performances not overcoming our shocks of recognition.

At the end of this “Hamlet,” I felt at last as if I was getting a handle on the play (I never expect to fully understand it). It has been a long journey. I read it in high school, underlining the famous lines. I saw the Richard Burton film version, and later Olivier’s. I studied it in graduate school. I have seen it onstage in England and the United States (most memorably in Aidan Quinn’s punk version, when he scrawled graffiti on the wall: “2B=?”). Franco Zeffirelli’s version with Gibson came in 1991. I learned from them all.

One of the tasks of a lifetime is to become familiar with the great plays of Shakespeare. “Hamlet” is the most opaque. Branagh’s version moved me, entertained me and made me feel for the first time at home in that doomed royal court. I may not be able to explain Hamlet, but at last I have a better idea than Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.