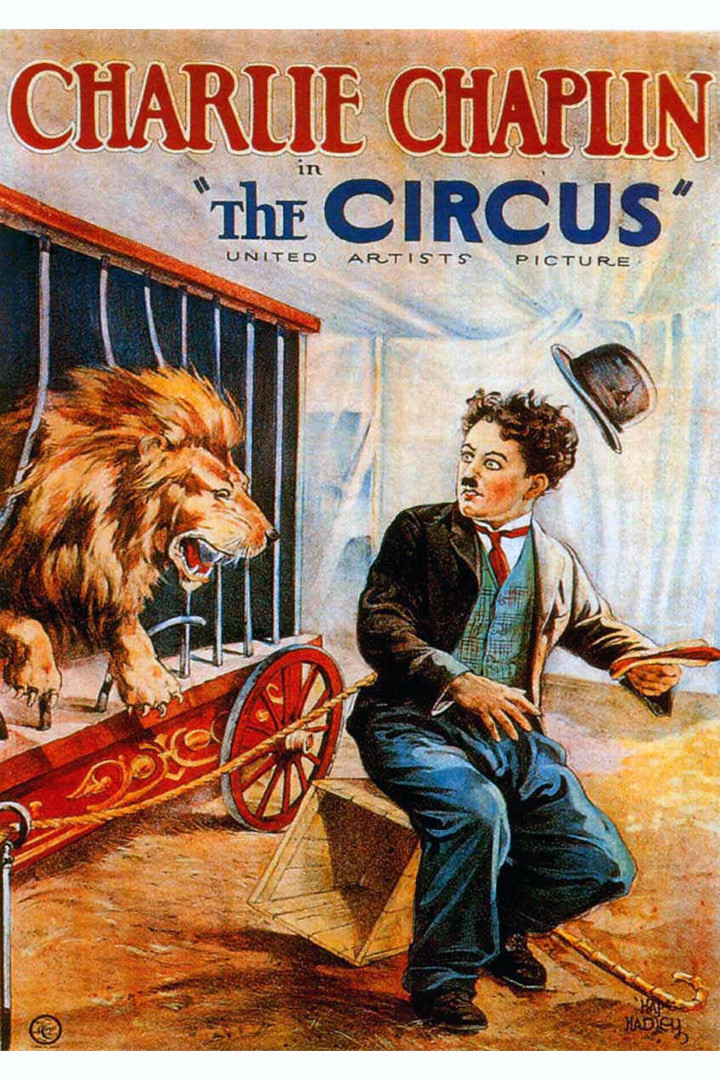

Charlie Chaplin was a perfectionist in his films and a calamity in his private life. These two traits clashed as he was making “The Circus,” one of his funniest films and certainly the most troubled. When he sat down to write his autobiography, he simply never mentioned it, perhaps because he wanted to sidestep that entire period. Yet a delightful movie emerged from the turmoil.

When he released it in 1928, Charlie was long since established as the greatest star in Hollywood. He must have feared the advent of the talkies, which by bringing sound to the movies would rob him of his silence. But more than sound was on his mind during the two years it took him to finally finish his production.

Always attracted to young girls, he married the 16-year-old Mildred Harris in 1918, when he was 29. After affairs with Pola Negri and Marion Davies, in 1924 he married Lita Grey, who said she was 16 but may have been 15. He learned she was pregnant while preparing “The Circus,” and after she sued for divorce and threatened scandal, her family scented a big settlement. They agreed on $600,000, while the IRS simultaneously determined he owed $1 million in back taxes.

Meanwhile, Chaplin had hired Lita’s friend Merna Kennedy as his lead in “The Circus”; Lita charged that they had an affair, and he also had an affair during the same period with the great silent star Louise Brooks. There were also rumors of wild parties, apparently true; his genitals led an undisciplined existence.

I mention these matters to underline his accomplishment with “The Circus.” Calamities struck the production. The circus tent set burned down. A reel of finished film was lost. His perfectionism demanded 200 takes for a difficult scene on a tightrope. He was divorcing Grey, romancing at least two other women, his funds were in disarray, the talkies were coming and yet his Little Tramp carried on unperturbed.

It’s interesting to ponder how smart the Tramp really is, and how much he understands the situations he finds himself in. He’s sort of a Holy Fool. In “The Circus,” he gets hired as a clown by accident after he proves so incompetent as a property man that he steals the laughter from the real clowns. He’s the star of the circus, but has to have this explained to him by Merna, who plays the ringmaster’s mistreated stepdaughter. He has no idea what made him funny, no clear idea of why he stops being funny, and usually seems the unwitting pawn of events outside his comprehension.

This makes him, for me, a little less inspired than Buster Keaton, whose characters are smart and calculating, if also beset by life’s disappointments. But both get many of their laughs by their sheer physical grace and acrobatic skills. The physical world conspires against them, and they prevail. They are often yearning romantics, with this difference: Buster seems a plausible mate, and the Tramp hardly seems to possess a libido, only idealized notions. If their comedies had been made in a more liberated time, it is possible to imagine Keaton in bed with a woman, but disquieting to think of the Tramp as a sexual being.

Yet here he contrives a giant crush on Merna (the character takes the actress’ name). They are brought together in the first place by one of the constant motifs in Chaplin, hunger. In “The Gold Rush,” he had eaten a shoe, and now his only piece of bread is stolen by the girl, who has been forbidden to eat as the ringmaster’s punishment for a bad performance. At one point, he slyly filches a baby’s bun. Later, in a lovely bit of pantomime, he rehearses for a comic bit as William Tell’s son, but grabs stolen bites of the apple. Merna and the Tramp are brought together in the first place as comrades in hunger and travail, and in the Tramp’s mind, they’re lovers.

The film is rich in sight gags. It opens with a complex pickpocket scenario, continues with a famous chase around the fairgrounds, includes a house of mirrors scene in which multiple Tramps, cops and strangers chase one another’s reflections. One scene has him locked in a lion’s cage; measures must have been taken to assure his safety, but CGI was unknown and the lion seems real enough. The editing here, coordinating the lion and the Tramp, must have been daunting. There are also bits showing Chaplin’s flawless timing, as when he wreaks havoc with the magician’s elaborate tricks.

The piece de resistance is the extended tightrope scene. The Tramp watches morosely as Rex, King of the Air (Harry Crocker), performs on the high wire, and Merna sighs and bats her eyes. Later Rex misses a performance, and the Tramp seizes the chance to go on the wire himself to win back her admiration. With the device of a secret safety wire supposedly manned by a prop man, he performs stunts that are extraordinary because of their difficulty; he uses the wire as a means of making the performance much harder than ordinary tightrope walking would be.

Yes, camera angles no doubt disguise his distance from the ground. Yes, there must have been a net. Yes, the “wire” must have only been the half of it. But still, what remarkable agility, a reminder of a time when Chaplin and other great stars (Fairbanks, Keaton, Lloyd) did their own stunts and could be seen doing them. And the addition of the pestering monkeys is a masterstroke.

The ending is rather a letdown, involving the Tramp’s oddly motivated reasons for reuniting Merna and Rex. There is a comeuppance for the ringmaster, and then, of course, the familiar closing iris shot of the Tramp, alone and forlorn but with a defiant little hop, going back on the road.

Chaplin was a considerable artist, brave and gifted, but I am in a minority in placing him second to Keaton among the silent clowns. My reasons for that are admittedly impulsive: I sense Keaton was the better man. Chaplin was so famous, so rich, so powerful when so young that there is a kind of conceit in the Tramp, a reverse noblesse oblige. Yes, he had a miserable childhood, and in his films, he often plays the friend of waifs, but there’s an air of back-patting about it. The Buster Keaton character has his feet on the ground. He would be embarrassed to parade his goodness. He uses ingenuity rather than divinity. Chaplin’s untidy love life suggests he felt he deserved whomever he wanted; Keaton in private life seems to have been melancholic because of alcoholism, but a decent enough sort with women.

But is this merely arbitrary judgment on my part? No doubt. A lesser man can make a better film, and a great man can make a bad one. I feel Keaton’s work has aged better than Chaplin’s. His films are drier, less lachrymose, less in love with their hero. Audiences still snuffle on cue at the end of “City Lights,” when the little blind flower girl discovers the identify of her benefactor. I’m touched, too. But it’s a set-up, isn’t it? You write a movie in which you are the benefactor of a blind flower girl, you’re gonna come out looking great. Buster is engaged in immediate practical problems.

I realize these are cavils. The wonderment is that we still have the silent clowns, many now available in restored versions. Almost all of Keaton, of Lloyd, of Chaplin. They were artists who depended on silence, and sound was powerless to add a thing. They live in their time, and we must be willing to visit it. An inability to admire silent films, like a dislike of black and white, is a sad inadequacy. Those who dismiss such pleasures must have deficient imaginations.

Also in the Great Movies Collection: “City Lights,” “Modern Times” and “The Great Dictator.”