If Walt Disney‘s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” had been primarily about Snow White, it might have been forgotten soon after its 1937 premiere, and treasured today only for historical reasons, as the first full-length animated feature in color. Snow White is, truth to tell, a bit of a bore, not a character who acts but one whose mere existence inspires others to act. The mistake of most of Disney’s countless imitators over the years has been to confuse the titles of his movies with their subjects. “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” is not so much about Snow White or Prince Charming as about the Seven Dwarfs and the evil Queen–and the countless creatures of the forest and the skies, from a bluebird that blushes to a turtle who takes forever to climb up a flight of stairs.

Walt Disney’s shorter cartoons all centered on one or a few central characters with strongly-defined personalities, starting with Mickey Mouse himself. They lived in simplified landscapes, and occupied stories in which clear objectives were boldly outlined. But when Disney decided in 1934 to make a full-length feature, he instinctively knew that the film would have to grow not only in length but in depth. The story of Snow White as told in his source, the Brothers Grimm, would scarcely occupy his running time, even at a brisk 83 minutes.

Disney’s inspiration was not in creating Snow White but in creating her world. At a time when animation was a painstaking frame-by-frame activity and every additional moving detail took an artist days or weeks to draw, Disney imagined a film in which every corner and dimension would contain something that was alive and moving. From the top to the bottom, from the front to the back, he filled the frame (which is why Disney’s decision in the 1980s to release a cropped “widescreen” version was so wrong-headed, and quickly retracted).

So complex were his frames, indeed, that Disney and his team of animators found that the cels they used for their short cartoons were not large enough to contain all the details he wanted, and larger cels were needed. The film’s earliest audiences may not have known the technical reasons for the film’s impact, but in the early scene where Snow White runs through the forest, they were thrilled by the way the branches reached out to snatch at her, and how the sinister eyes in the darkness were revealed to belong to friendly woodland animals. The trees didn’t just sit there within the frame.

Disney’s other innovation was the “multiplane camera,” which gave the illusion of three dimensions by placing several levels of drawing one behind another and moving them separately–the ones in front faster than the ones behind, so that the background seemed to actually move instead of simply unscrolling. Multiplane cameras were standard in animation until the very recent use of computers, which achieve a similar but more detailed effect–too detailed, purists argue, because too lifelike.

Nothing like the techniques in “Snow White” had been seen before. Animation itself was considered a child’s entertainment, six minutes of gags involving mice and ducks, before the newsreel and the main feature. “Snow White” demonstrated how animation could release a movie from its trap of space and time; how gravity, dimension, physical limitations and the rules of movement itself could be transcended by the imaginations of the animators.

Consider another early example, when Snow White is singing “I’m Wishing” while looking down into the well. Disney gives her an audience–a dove that flutters away in momentary fright, and then returns to hear the rest of the song. Then the point of view shifts dramatically, and we are looking straight up at Snow White from beneath the shimmering surface of the water in the well. The drawing is as easy to achieve as any other, but where did the imagination come from, to supply that point of view?

Walt Disney often receives credit for everything done in his name (even sometimes after his death). He was a leader of a large group of dedicated and hard-working collaborators, who are thanked in the first frames of “Snow White,” before the full credits. But he was the visionary who guided them, and it is a little stunning to realize that modern Disney animated features like “Beauty and the Beast,” “The Lion King” and “Aladdin,” as well as the rare hits made outside the Disney shop, like Dreamworks’ “Shrek” and Pixar’s “Toy Story,” still use to this day the basic approach that you can see full-blown in “Snow White.”

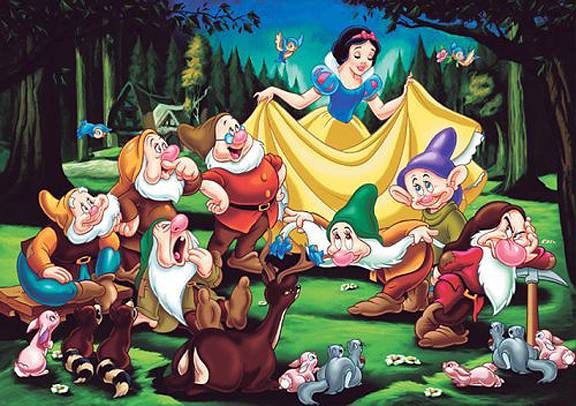

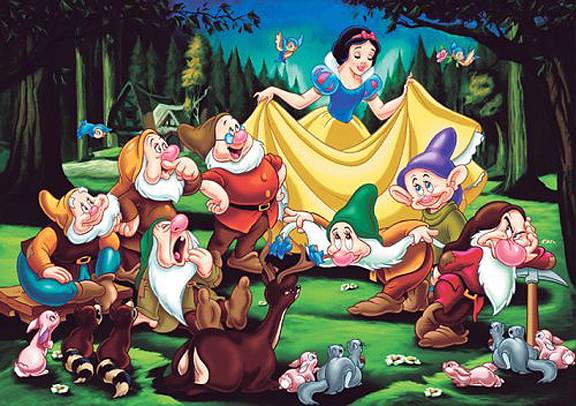

The most important continuing element is the use of satellite and sidekick characters, minor and major, serious and comic. A frame is not allowed for long to contain only a single character, long speeches are rare, musical and dance numbers are frequent, and the central action is underlined by the bit characters, who mirror it or react to it.

Disney’s other insight was to make the characters physically express their personalities. He did that not by giving them funny faces or distinctive clothes (although that was part of it) but studying styles of body language and then exaggerating them. When Snow White first comes across the cottage of the dwarfs, she goes upstairs and sees their beds, each one with a nameplate: Sleepy, Grumpy, Dopey, and so on. When the dwarfs return home from work (“Heigh-ho! Heigh-ho!”) they are frightened and resentful to find a stranger stretched across their little beds, but she quickly wins them over by calling each one by name. She knows them, of course, because they personify their names. But that similarity alone would soon become boring if they didn’t also act out every speech and movement with exaggerated body language, and if their very clothing didn’t seem to move in sympathy with their personalities.

Richard Schickel’s 1968 bookThe Disney Versionpoints out Disney’s inspiration in providing his heroes and supporting characters with different centers of gravity. A heroine like Snow White will stand upright and tall. But all of the comic characters will make movements centered on and emanating from their posteriors. Rump-butting is commonplace in Disney films, and characters often fall on their behinds and spin around. Schickel; attributed this to some kind of Disney anal fixation, but I think Disney did it because it works: It makes the comic characters rounder, lower, softer, bouncier and funnier, and the personalities of all seven Dwarfs are built from the seat up.

The animals are also divided into body styles throughout Disney. “Real” animals (like Pluto) look more like dogs, comic animals (like Goofy) stand upright and are more bottom-loaded. In the same movie a mouse will be a rodent but Mickey will somehow be other than a mouse; the stars transcend their species. In both versions, non-star animals and other supporting characters provide counterpoint and little parallel stories. Snow White doesn’t simply climb up the stairs at the dwarves’ house–she’s accompanied by a tumult of animals. And they don’t simply follow her in one-dimensional movement. The chipmunks hurry so fast they seem to climb over each other’s backs, but the turtle takes it one laborious step at a time, and provides a punch line when he tumbles back down again.

What you see in “Snow White” is a canvas always shimmering, palpitating, with movement and invention. To this is linked the central story, which like all good fairy tales is terrifying, involving the evil Queen, the sinister Mirror on the Wall, the poisoned apple, entombment in the glass casket, the lightning storm, the rocky ledge, the Queen’s fall to her death. What helps children deal with this material is that the birds and animals are as timid as they are, scurrying away and then returning for another curious look. The little creatures of “Snow White” are like a chorus that feels like the kids in the audience do.

“Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” was immediately hailed as a masterpiece. (The Russian director Sergei Eisenstein called it the greatest movie ever made.) It remains the jewel in Disney’s crown, and although inflated modern grosses have allowed other titles to pass it in dollar totals, it is likely that more people have seen it than any other animated feature. The word genius is easily used and has been cheapened, but when it is used to describe Walt Disney, reflect that he conceived of this film, in all of its length, revolutionary style and invention, when there was no other like it–and that to one degree or another, every animated feature made since owes it something.