Fathered by strangers, abandoned by their mothers, thrown away by society, the children of “Pixote” live by their wits on the cruel streets of Sao Paolo in Brazil. They improvise their own families, forming shifting alliances based on need, fear and even love. Their economy is based on the only two markets open to them, those for sex and drugs. Many of them are so young, they only vaguely understand sex; they are hardened to sights and experiences they even don’t comprehend.

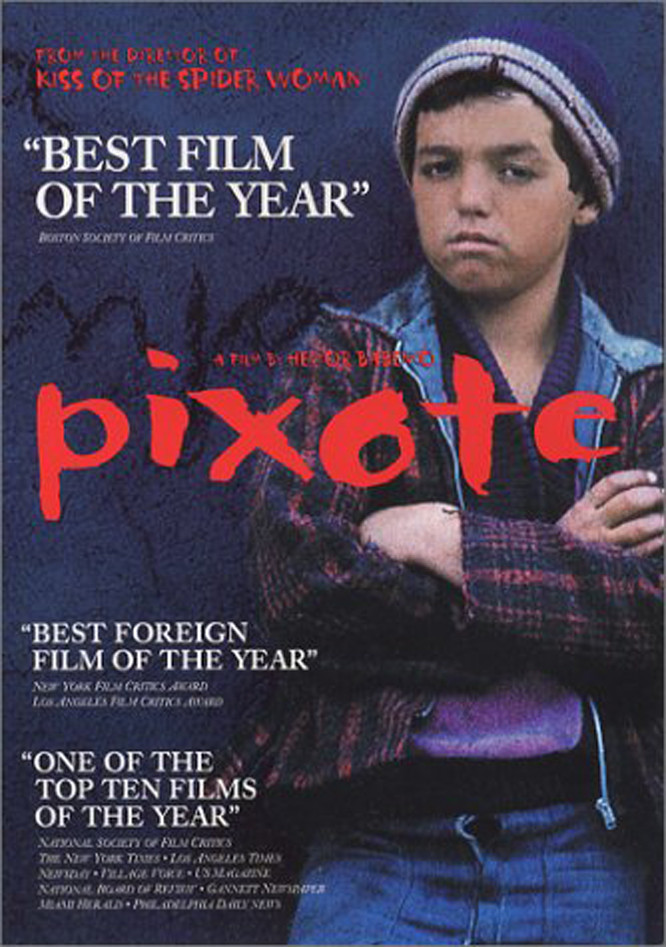

Hector Babenco’s 1981 film was created in the spirit of Italian neo-realism; his child actors are the real thing, discovered in the streets and essentially playing themselves. The adult characters are mostly played by professional actors, but these performances coming from completely different backgrounds seem to feed from the same desperation. There is no answer to the problem of the millions of homeless children, no remedy, no hope. It is not surprising to learn that Fernando Ramos da Silva, the illiterate 11-year-old who plays Pixote, returned to the streets and was killed by police bullets in 1987.

The movie is told in a loosely structured, episodic style. Not every scene pays off neatly or makes a smooth connect with the next one. The jagged tone seems appropriate for these lives, which have no continuity, no balance point, no reason for something to happen today, tomorrow or ever.

In a society of children and adolescents who have no homes and no money, crime is the natural way of survival, but they’re not very good at it (the gangs in “City of God,” made 20 years later, are much more sophisticated). Their approach to crime, as to life, is thoughtless improvisation; they respond to situations, but have no control over them. We sense that Babenco isn’t leading his characters but following them, and scenes don’t always have a point or a purpose because neither do these lives.

We meet Pixote when he is rounded up along with other street kids after the murder of a judge. Society demands the appearance of justice and revenge, and so the murder will be pinned on one of them — never mind if it’s the right one or not. Some fairly confusing dialogue indicates that one of these kids may have been involved in the crime, or witnessed it, but solving the crime is not the point of the movie, and the police despair of ever knowing who the real killer is. The code of silence, enforced by the possibility of death, is complete.

The kids are taken to a reformatory. Inside would be better for them than outside, if it weren’t for the brutality of the guards, the corruption of the staff and the crimes of one prisoner against another (on his first night, Pixote witnesses a rape).

Faces and characters form out of the crowd. The most striking is Lilica (Jorge Juliao), a transvestite whose sexual nature is accepted casually by the others. He’s older — 17, in a nation where he can’t be charged with a crime until he’s 18. Then there are Dito (Gilberto Moura), looking cherubic under a crown of curly hair, and Chico (Edilson Lino).

Without agreeing to it, discussing it or even really noticing it, they form a group based on their shared vulnerability and trust. When things get dangerous inside the reformatory, and it’s clear some of them may die at the hands of brutal guards or cops with secrets to hide, they escape and return to the streets. It’s not that hard: they go through an open window to a rooftop. (One kid, with a leg brace, decides not to escape: “It’s better for me here.”)

We can anticipate, more or less, what happens in the first half of the film, which is not a million miles from the poverty and crime in, say, Oliver Twist. The second half of the film is a descent into hell; indeed, the dominant tones become red and orange instead of the muted drabness of the earlier scenes.

Lilica is picked up by a sometime client or lover or pimp named Cristal (Tony Tornado). He can wholesale them some drugs. They snatch purses to raise the cash, prowling the city streets like a wolf pack. They ride the rails to Rio to sell the drugs, are victimized by their customers and end up living with a deteriorating prostitute named Sueli (Marilia Pera, who won the best actress award from the National Society of Film Critics).

She is the fifth member of the family, but then it begins to shrink. Two of the boys are killed, and Lilica walks out one night — jealous because the prostitute has seduced a boy he cares for. Even earlier, Lilica was uneasy around Sueli, and indeed, he seems more feminine, more maternal, more caring than the hard woman of the streets. Lilica has a self-awareness the others lack, sighing at one point, “What can a queer expect from life?” Pixote replies, “Nothing, Lilica,” but in his world no one can expect anything. Then Lilica is gone, and at the end, everyone is gone, except for Sueli and Pixote.

Pixote has obtained a gun, and he uses it. How, I will not reveal, except to say that it is shocking how impassive he seems after killing two people, one by mistake. His wide, open eyes don’t seem to register the result of his actions, and his face doesn’t seem to register feeling about it — until, hours later, sitting at the foot of Sueli’s bed, watching TV, he throws up. And then we understand the agony inside of Pixote, the pain that is unbearable because he lacks the experience and even the words to deal with it.

The closing scenes are powerful, sad and eventually heartless. They show without compromise the depth of Pixote’s need and the totality of his loneliness. Much depends on the character of Sueli, who in the second half of the movie is really the dominant presence (Pixote throughout most of the movie is as much observer as participant).

The streets have given Sueli a hardness and coldness that close her off from real emotion, even though as an experienced prostitute she can fake it — sometimes with clients, but more often in her own life, as if she’s trying to deceive herself. She has a remarkable scene, late one night when she should be in torment but gets drunk and then dances in the headlights of a stolen car, remembering that she was truly happy when she was a strip-tease performer.

Then comes her last scene with Pixote, which is so sorrowful and cruel it is barely watchable. He is still, after everything, a little boy. Sueli has recently performed an abortion on herself (she explains it in cruel detail to Pixote), but now, just for a moment, she imagines a life in which she will return to her town and family, and Pixote will be like her son. Pixote turns to her breast, not in a sexual way, but in need, and we see the child who has always hungered for a mother he never had.

It is a hushed, sacred moment, and in another film, it would be the last shot. A similar scene concludes John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath— the novel, not the movie. But then Sueli hardens, and all the anger of her pitiful life focuses on Pixote. At this point the film fits the classical definition of tragedy, which requires the death of a hero. But Pixote is not a hero; his life has been a half-understood reaction to events. And he doesn’t die, except in his heart and soul.

Babenco, born in 1946, has been one of Brazil’s most successful directors. “Pixote” was his first great accomplishment, and in 1985, he made “Kiss of the Spider Woman,” with its best actor Oscar for William Hurt and a nomination for Babenco. Then came two big-budget American films with mixed receptions, “Ironweed” (1987), with Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep, and “At Play In The Fields Of The Lord” (1991). In 2003 he returned to the homeless and helpless of Brazil with “Carandiru,” set in the most notorious prison in Brazil and once again showing transvestites and thieves forming their own society in opposition to the corruption of the system.

But “Pixote” stands alone in his work, a rough, unblinking look at lives no human being should be required to lead. And the eyes of Fernando Ramos da Silva, his doomed young actor, regard us from the screen not in hurt, not in accusation, not in regret — but simply in acceptance of a desolate daily reality.

“Pixote” is available on DVD. See also Ebert’s “Great Movie” essays on the Italian neo-realist classics “The Bicycle Thief” and “Nights of Cabiria” atwww.suntimes.com/ebert/greatmovies/.