The key action in Claude Jutra’s “Mon Oncle Antoine” (1971) takes place over a period of 24 hours in a Quebec mining town. Although the film begins earlier in the year, everything comes to a focus beginning on the morning of Christmas Eve and closing on the dawn of Christmas. During that time, a young boy has had his life forever changed. This beloved Canadian film is rich in characters, glowing with life in the midst of death.

The town is Black Hawk, surrounded by the slag heaps of asbestos mines. The action is “not so very long ago,” the 1940s. The town is poor, and people still live in old-fashioned ways and travel by horse, carriage or train. The film opens with an argument between a Quebecois mine worker named Joe Paulin (Lionel Villenuve) and his English-speaking boss. We soon understand that Joe hates the “English” and hates the mine, and he quits on the spot, says farewell to his family, shoulders his ax and heads off to a logging camp where nobody will be on his case. We won’t see much of him again until the film’s conclusion.

The central story opens with a funeral, and we are given to understand that the deceased died of lung disease, contracted in the mines. The funeral is a sad affair; the dead man’s naked body is covered with a rented suit-front, the flowers are all fake, the undertaker takes back the rosary to be used again.

The undertaker is Antoine (Jean Duceppe) and his assistant is a robust man in his 30s named Fernand (Claude Jutra himself). They return after the ceremony to the general store that Antoine owns with his wife, Cecile (Olivette Thibault). Soon we meet Benoit (Jacques Gagnon), the orphaned 14-year-old who lives with them, and also the pretty young Carmen (Lyne Champagne), a clerk who boards with them.

This store will be the principal location for the movie, and it is a masterful re-creation from the period. Groceries are on the right as you enter, dry goods on the left, hardware upstairs, along with caskets for the undertaking business. The local people all know each other’s business and meet here to gossip. On Christmas Eve, there is a festive air. Benoit and Carmen are up early to decorate the window. Benoit’s Uncle Antoine is up later, disheveled, and repairs behind the windowpanes of the store office to pour himself a little drink.

Benoit regards him through the panes, silently. Benoit sees everything, is solemn and quiet, except with his pals or Carmen, when he is a playful boy. During this day, there will be great drama attending the unveiling of the Nativity scene in the store window. Enormous excitement when Alexandrine, the accountant’s wife, goes upstairs with Cecile to try on a corset. Jollity as Antoine sells an old rummy a pair of pants twice too large for him. Celebration when a young woman shyly asks to see a bridal veil. Discovery when Benoit and Carmen wrestle upstairs, he grabs her breast through her dress, she stays perfectly still, and a wordless communication passes between them.

Outside on the main street, the sour-faced, hated mine owner trots in his carriage, tossing cheap Christmas stockings at the homes of his employees. Is it an accident they mostly land in the mud? The subtext of the film is that these mine workers are all treated as serfs and are working at a deadly trade. Jutra’s film was made at the height of Quebec separatism, and although it is never specific in its politics, of course they are unmistakable.

There are small human scenes. A little flirtation between Antoine and Cecile. Another little flirtation between Cecile and Fernand. Benoit’s infatuation with Carmen. Carmen’s sadness when her father appears to collect her wages and doesn’t even wish her a merry Christmas. The ferocity with which Antoine withholds $5 for Carmen herself: “That’s how it is!”

We have seen scenes at the rural home of the Paulin family and know that the eldest son is ill. The store’s telephone rings, and it is Madame Paulin (Helene Loiselle), telephoning to say that her son has died. Can Antoine come to take the body? Now begins the great sequence of the film that carries all its meaning and pays off on all its implications. Benoit begs to be allowed to go along with his uncle on the carriage ride through a developing blizzard, and they head out to the Paulin home, Antoine drinking steadily. Not to fear: The horse knows the way.

This journey certainly looks like the real thing, the wind-blown snow cutting into their faces as they huddle in their winter fur coats. At the lonely Paulin home, Benoit as usual sees all, says nothing, as Antoine, now thoroughly drunk, uses his fingers to eat the hot meal Madame Paulin has prepared. Benoit’s eyes are drawn to a corner of the room where a dark doorway stands partly open. In there, he knows, is the dead boy, scarcely older than himself.

On the journey home, the coffin is lost: It falls from the carriage bed. Antoine is too drunk to help Benoit drag it back on board and suddenly unburdens himself of a lifetime of grief: He hates the country, is afraid of corpses, his wife never gave him a child. Benoit sees how it really is, and the lessons will continue during this evening. The emergency is entirely in his hands. What he does is inevitable and responsible and leads to a heartbreaking conclusion, once again witnessed through a window with Benoit’s solemn eyes.

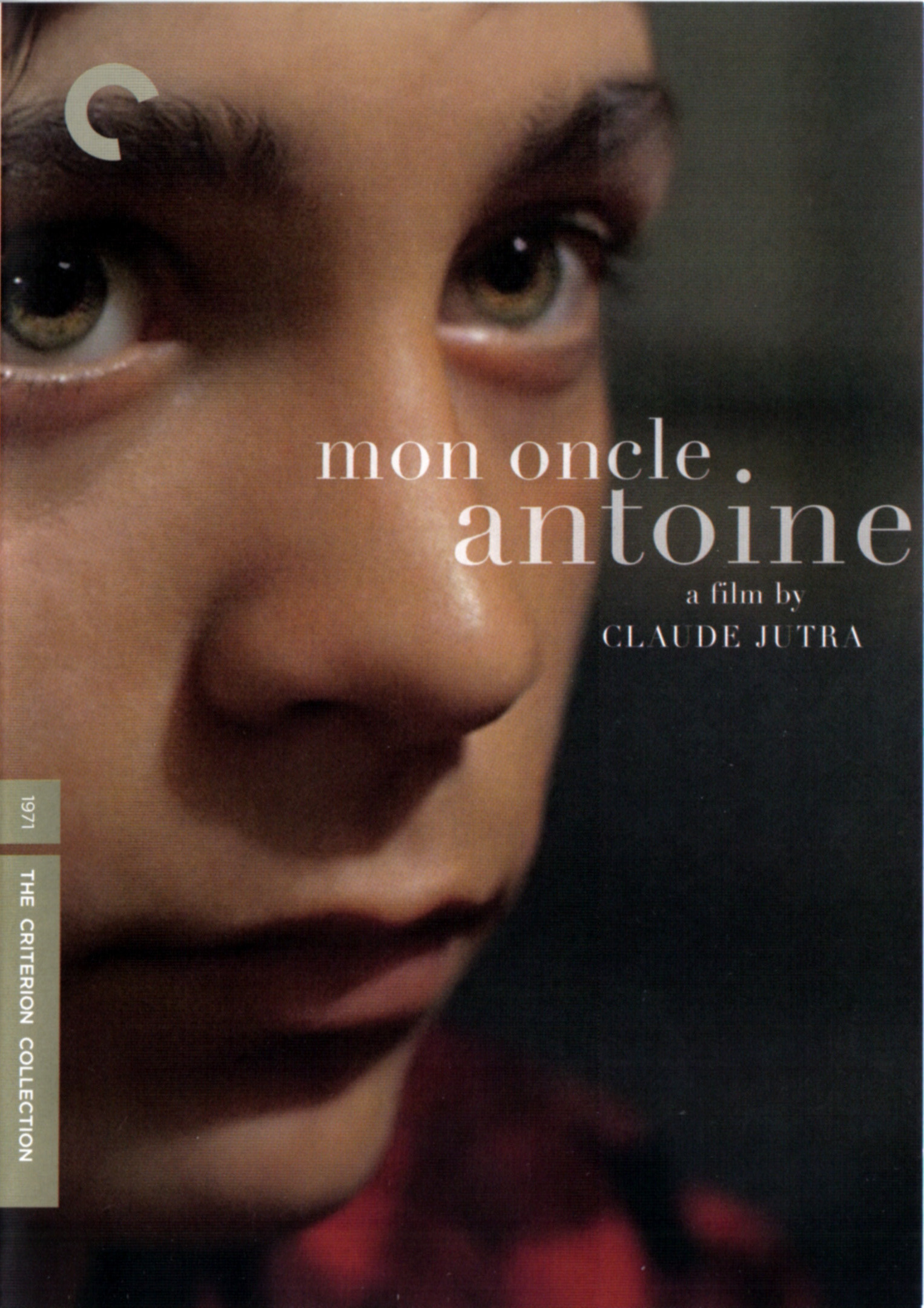

That “Mon Oncle Antoine” is such a fine film only underlines the tragedy of the director’s later life. Jutra had started full of promise. He first studied medicine, then became a student at the National Film Board of Canada (which produced this film). He worked in France as an apprentice to Truffaut. He worked with a script by Clement Perron, who was inspired by events in his own life. Jutra made other films before learning he was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s. He disappeared in the winter of 1986, and his body was found in the St. Lawrence River the next spring. He was presumably a suicide. He made an earlier film in which the character leaps into the same river.

What he left behind is a film to treasure, not least because of the way it uses its locations. The slag heaps of the mines overshadow the town below, and there is a high-angle shot establishing how vast they are and how small the town is — just a few square blocks and muddy streets. It must still have been thus when he filmed. The storefronts and interiors do not look like sets — not even the store, although we know it surely is. There is not an automobile in sight, nor would one have gotten far on these roads in the winter. The faces of many of the extras betray a heavy load of work and disappointment. Social commentary is buried all through the film, as in the contrast between the working women and the haughty wife of the mine accountant.

In the loneliness and grandeur of the midnight journey of Benoit and Antoine, there is a haunting beauty. I was reminded of the moods of Willa Cather’s Shadows on the Rock, and, indeed, in the Paulin family, Cather’s novels of American pioneers surviving the cold. Jutra and his screenwriter clearly know these people and this land, and tell their stories with confidence and familiarity. There is a tendency to assume a movie titled “My Uncle Antoine” will be a fond memoir of a lovable old curmudgeon. Not this time. There is that in Antoine that is lovable, and that which is happy, and that which is tragic. So it is. As Benoit learns.