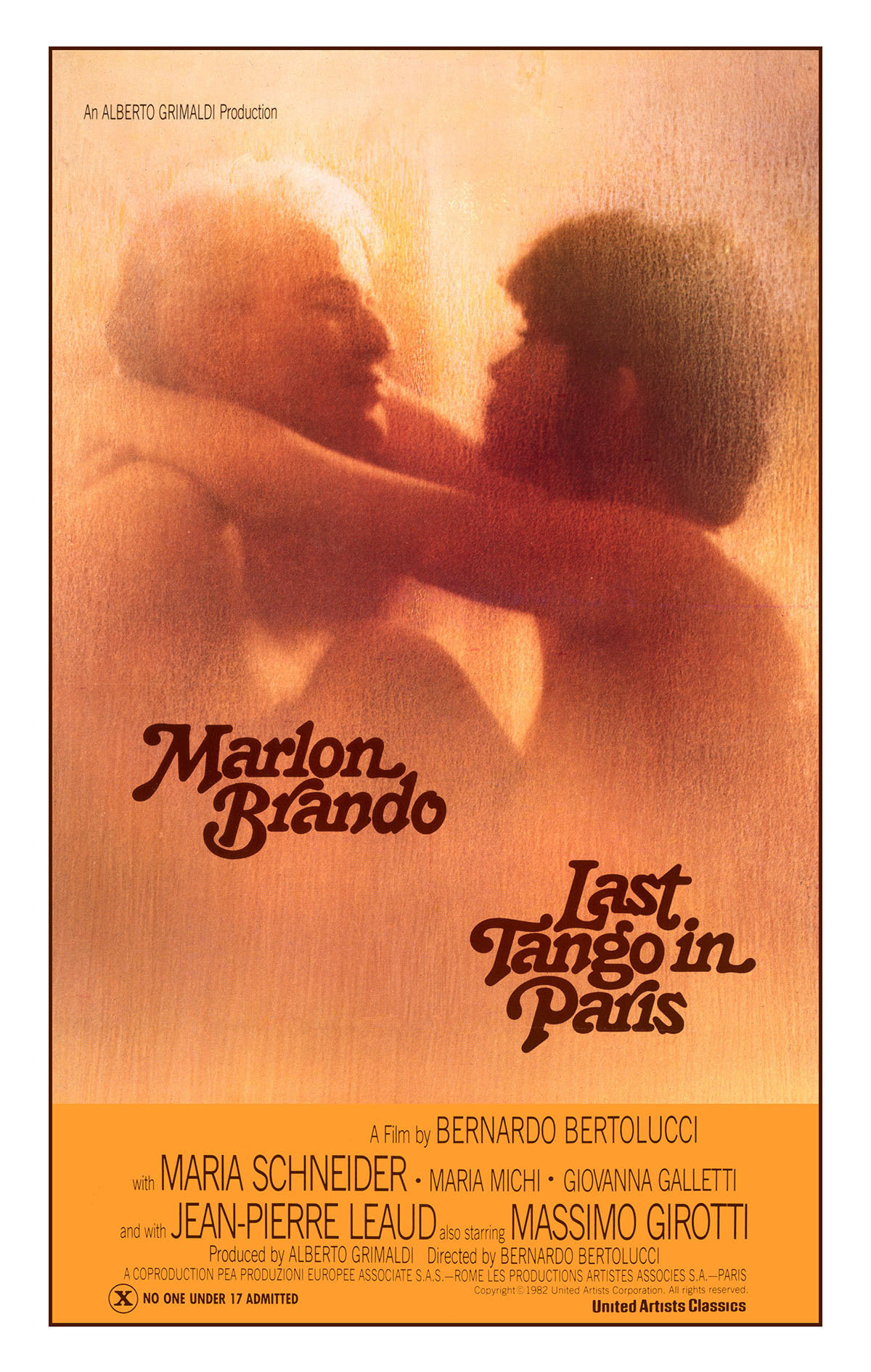

Reviewing “Last Tango in Paris” in 1972, I wrote that it was one of the great emotional experiences of our time, adding: “It’s a movie that exists so resolutely on the level of emotion, indeed, that possibly only Marlon Brando, of all living actors, could have played its lead. Who else can act so brutally and imply such vulnerability and need?”

Now it is 2004 and Brando is dead. As I looked at the film yet again, Brando’s most powerful scene resonated for me in an unexpected way. The scene where he confronts the body of his wife, who has committed suicide, and mourns her in an outpouring of rage and grief. “I may be able to comprehend the universe, but I’ll never understand the truth about you,” he says. He calls her vile names, then is torn by sobs. He tries to wipe off her cosmetic death mask (“Look at you! You’re a monument to your mother! You never wore makeup, never wore false eyelashes.”). He doesn’t understand why she killed herself, why she abandoned him, why she never really loved him in the first place, why he was always more of a guest in her hotel than a husband in her bed.

As I watched this scene, I was struck by a strange notion. I watched it again, this time imagining that Brando was talking to his own dead body — that his anger and love, his blame and grief, were directed toward himself. I’m sure Bernardo Bertolucci, the film’s director, did not have this in mind, and of course I cannot know what Brando was thinking. But here was a man who sometimes prostituted his own talent, who frustrated his admirers by seeming to scorn them, whose “eventual monstrous obesity seemed a clear sign of his hatred for Hollywood,” as Stanley Kauffmann wrote in the best of the Brando obituaries. This was the greatest movie actor of his time, the author of performances that do honor to the cinema, and yet as Kauffmann notes, he was driven to disparage the profession of acting, which was the instrument of his genius.

His wife in “Last Tango in Paris” owned and ran a little hotel. “It’s kind of a dump, but not completely a flophouse,” he says, but the film clearly shows it as a place where prostitutes bring their clients. So he was living off a woman who lived off whores. “I moved in for one night and stayed five years,” he muses. Can this refer to his love-hate for Hollywood, for acting, for his own career, for the waste he was sometimes compelled to make of his talent? Is it himself that he’ll never understand the truth about?

We cannot know. These ideas exist in my mind, and it is wrong to place them in Brando’s. But such a narcissistic actor never held more love and grief for anybody else than he held for himself, and I say that not as an insult but as a way of explaining his power: In his best performances, he is sorry for himself. We see the wounded little boy — quite clearly, for example, in the monologue in “Last Tango” recalling his character’s childhood. Yes, at the end he was fat. A lot of people get fat. But what a thing to happen to Marlon Brando. How better to destroy an actor’s vanity, how better to force us to admire him for himself and not because Stanley Kowalski looked sexy in a torn T-shirt? Did he eat as he did out of self-pity, because he felt he deserved to, because he felt deprived?

The history of “Last Tango in Paris” (1972) has and always will be dominated by Pauline Kael. “The movie breakthrough has finally come,” she wrote, in what may be the most famous movie review ever published. “Bertolucci and Brando have altered the face of an art form.” She said the film’s premiere was an event comparable to the night in 1913 when Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring” was first performed and ushered in modern music. As it has turned out, “Last Tango” was not a breakthrough but more of an elegy for the kind of film she championed. In the years since, mass Hollywood entertainments have all but crushed art films, which were much more successful then than now. Although pornography documents the impersonal mechanics of sex, few serious films challenge actors to explore its human dimensions; isn’t it remarkable that no film since 1972 has been more sexually intimate, revealing, honest and transgressive than “Last Tango”?

The film begins when Paul (Brando) and Jeanne (Maria Schneider) meet in a Paris apartment they are both considering renting. Paul, we will learn, is planning a move from his dead wife’s hotel. Jeanne is planning marriage with Tom (Jean-Pierre Leaud), an insipid young director. Within moments after they meet, Paul forces sudden, needful sex upon her. It would be rape were it not that Jeanne does not object or resist, makes her body available almost with detachment. Indeed, it is rape in Paul’s mind, Paul’s sexual release seems real, here and throughout the film, but we are never sure what Jeanne feels during their sex. Although she cries during the famous “butter scene,” she is not crying about the sex and indeed doesn’t seem to be thinking about it.

Paul insists on “no names,” no personal histories. Their meetings in the apartment are not dates but occasions for sex, which he defines and she accepts. The pairing of the 20-year old girl and the unkempt 45-year-old man seems unlikely, but Bertolucci enriches it through their extraordinary dialogue. Brando and Schneider seem natural and spontaneous. Their conversations are rare in not seeming written, not seeming to point to a purpose or conclusion; they are the sorts of things these people might really say, and it’s remarkable how relaxed, even playful and sweet, Paul can be with her, when he is not dictating their brutal sexual couplings (at no point can they be said to “make love”).

Schneider’s performance has been discounted over the years. This is said to be Brando’s film. “Both characters are enigmas,” I wrote in 1995, “but Brando knows Paul, while Schneider is only walking in Jeanne’s shoes.” Seeing the film again, I believe I was wrong. Schneider, who plays much of the film completely nude, who is held in closeup during long scenes of extraordinary complexity, who at 22 had hardly acted before, shares the film with Brando and meets him in the middle. What Hollywood actress of the time could have played Brando on his own field?

In 1995 I wrote: “He is in scenes as an actor, she is in scenes as a thing.” Wrong again. They are both in scenes as actors, but I was seeing her as a thing, fascinated by the disconnect between her adolescent immaturity and voluptuous body. I objectified her, but Paul does not, and neither does the movie. That he keeps his secrets, refuses intimacy, treats her roughly, is explained by the scene with the body of his wife, and perhaps by his own experience of sex.

When I interviewed her in 1975, Schneider said she and Brando improvised the bathroom scene — the scene where he shaves while they talk. Brando always liked to have something to do with his hands, some kind of business, and here their dialogue is as close to overheard real conversation as it is probably possible to come. They even misspeak from time to time. There are little pauses and disconnects. The conversation seems to be finding its way.

In a film posited on two characters remaining strangers, Bertolucci and his actors achieve a kind of intimacy the movies rarely approach. Real behavior is permitted; in a scene with his wife’s lover Marcel, Paul coughs, and we sense that is Brando actually coughing, and accepting that he has coughed, and that in other movies actors never cough, except when it is in the screenplay.

The film is not perfect. The character of Tom is a caricature that only grows more distracting over the years. Leaud, the star of Truffaut’s autobiographical films, behaves not as if he is a movie director, but as if he’s playing one — not in this film but in another film, maybe a musical comedy. The dialogue between Tom and Jeanne seems unnatural and forced. We don’t believe it, and we don’t care.

What happens in the apartment between Paul and Jeanne is what the movie is about: How sex fulfills two completely different needs. Paul needs to lose himself to mourning and anger, to force his manhood on this stranger because he failed with his wife. Jeanne responds to a man who, despite his pose of detachment, is focused on her, who desperately needs her (if for reasons she does not understand). He is the opposite of Tom, who says he wants to film every moment of her life, but is thinking of his film, not of her. Jeanne senses that Paul needs her as she may never be needed again in all of her life. Her despair at the end is not because of lost romance, but because Paul no longer seems to need her.

Then there is the closing sequence, in which Paul abandons the behavior of the empty room, reveals his name, tells her about his life, seems to desire her in the banal way a middle-age man might desire a sexy girl. That changes everything. Is it plausible, what she does to him when he follows her into her mother’s apartment? I don’t know, but I know the movie could not end with both of them still alive. Much has been said about Brando’s death scene in “The Godfather,” but what other actor would have thought to park his chewing gum before the most important moment of his life?