History repeats itself, the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

This statement by Karl Marx admirably serves two functions: (1) It describes the difference between the two times the teaching of Darwin’s theories were put on trial in this country, in Tennessee in 1925 and in Pennsylvania in 2005; (2) Because it is from Karl Marx, it will automatically be rejected, along with the words to follow, by those who judge a statement not by its content but by its source. That is precisely the argument between Darwinism and creationism. Stanley Kramer‘s “Inherit the Wind” (1960) is a movie about a courtroom battle between those who believe the Bible is literally true and those who believe, as the Spencer Tracy character puts it, that “an idea is a greater monument than a cathedral.”

The so-called Monkey Trial of 1925 put a young high school teacher named John T. Scopes on trial for violating a state law, passed the same year, prohibiting the teaching of any theory that denied the biblical account of divine creation. Darwin’s theory of evolution was also therefore on trial. Two of the most famous lawyers and orators in the land contested the case. Scopes was defended by the legendary Clarence Darrow, and the prosecution was led by three-time presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. Darrow’s expenses were paid by the Baltimore Sun papers, home of the famed journalist H.L. Mencken, who covered the trial with many snorts and guffaws.

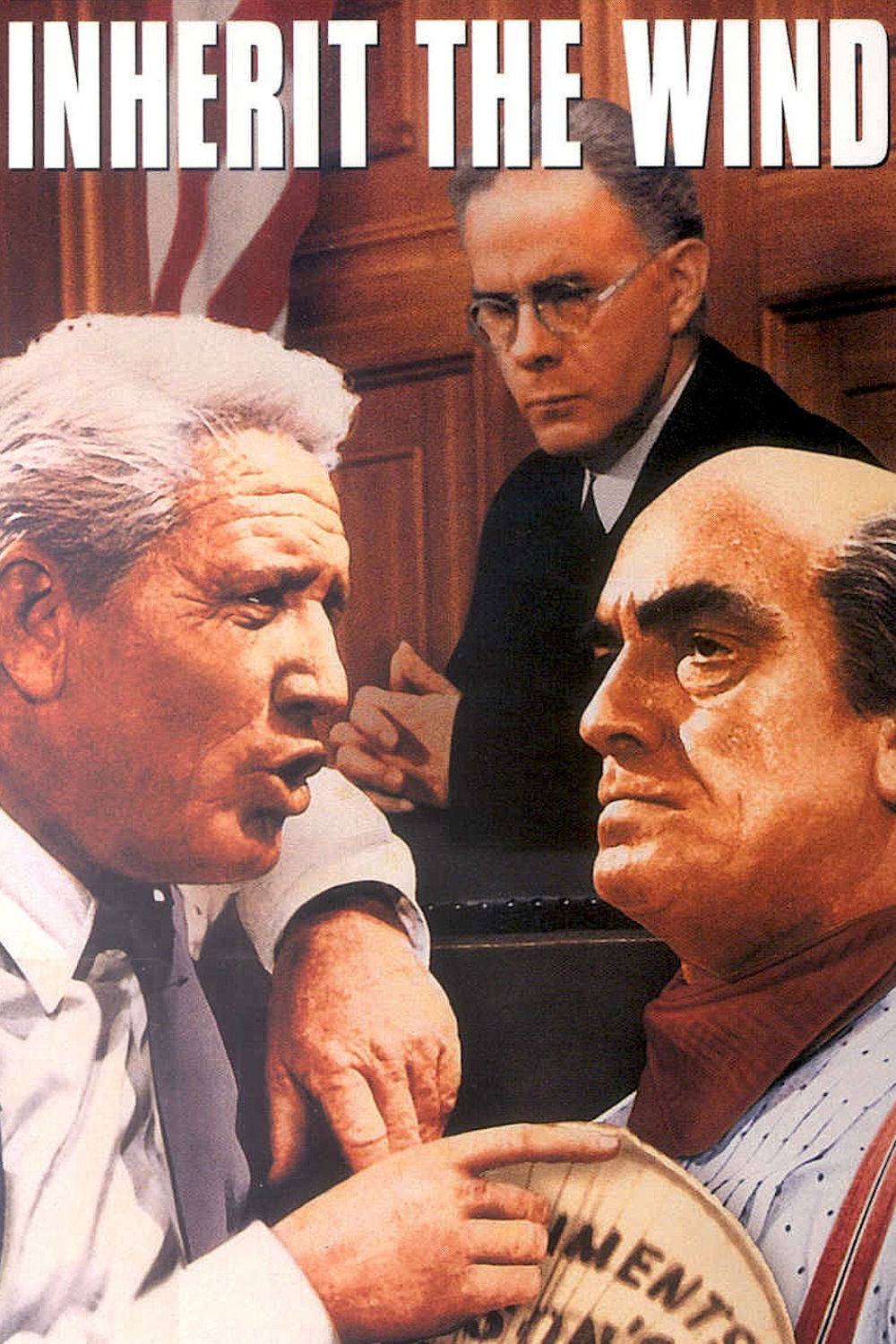

In Kramer’s film, Darrow becomes Henry Drummond (Spencer Tracy), Bryan is Matthew Harrison Brady (Fredric March), Mencken is E.K. Hornbeck (Gene Kelly), and Scopes is Bertram T. Cates (Dick York). Another major player is the gravel-voiced Harry Morgan, as the judge. So obviously were the characters based on their historical sources that the back of the DVD simply refers to them as “Bryan” and “Darrow,” as if their names had not been changed.

Seen 46 years after its release but only a few months after Darwin was once again on trial in Dover, Penn., “Inherit the Wind” is a film that rebukes the past when it might also have feared the future. Beliefs that seemed like ancient history to Kramer have had a surprising resiliency; two recent polls show that 38 percent of American teenagers believe “God created humans pretty much in their present form within the last 10,000 years or so,” and 54 percent of American adults doubt that man evolved from earlier species. There is hardly a politician in the land with courage enough to state that they are wrong.

Certainly most of the citizens in the movie’s fictional town of Hillsboro, Tenn., believe in the literal truth of Genesis. “There’s only one man in this town who thinks at all,” Drummond roars, “and he’s in jail.” The movie casts the battle as a struggle between the followers of a fundamentalist preacher (Claude Akins) and the snowy-haired agnostic Drummond, who believes Darwinism is as “incontrovertible as geometry,” as indeed it seems to well over 99 percent of the world’s scientists. The preacher’s followers descend on the town with tents, a Ferris wheel and a sideshow in which a monkey smokes a cigarette while a barker asks if men came from monkeys. There is a fraught romantic subplot: The defendant York is engaged to Rachel (Donna Anderson), the preacher’s daughter. At one point denouncing his daughter as a creature of the devil, the preacher froths so easily that he lacks credibility.

Early scenes in the film are broadly drawn; a parade welcomes Brady to town as the band plays “That Old-Time Religion,” and the Baltimore journalist speaks as if he is reading his own copy (“I’m admired for my detestability”). But once the film centers on the courtroom battle between the two old men, it finds a ferocity that is awesome; Brady and Drummond essentially engage in a debate between fundamentalism and the possibility that if God did create the world, he did so in more than six 24-hour days. What is astonishing in this 1960 film is the gutsy way it engages in ideas, pulls no punches in its language, and allows the characters long and impassioned speeches. There are a lot of words here, well-written and spoken, and not condescending to the audience. Both Tracy and March vent an anger and passion through their characters that ventures beyond acting into holy zeal.

I wonder if a film made today would have the nerve to question fundamentalism as bluntly as the Tracy character does. The beliefs he argues against have crept back into view as “creationist science,” and it was the notion that this should be offered as an alternative to Darwinism that inspired the 2005 Pennsylvania case. In the movie and in the actual Scopes trial, Bryan was a persuasive orator who proudly defended fundamentalism; his 2005 counterparts carefully distanced themselves from religious advocacy and tried to make their case on the basis of “creationist science.” Their presentation was so unpersuasive that Judge John E. Jones III (a Republican appointed by George W. Bush) not only ruled against them but added that they exhibited “striking ignorance” and “breathtaking inanity” and “lied outright under oath.”

Central to the case for “alternative” theories is a misunderstanding of what a scientific theory is, and isn’t. One thing it cannot do is depend on supernatural elements. That is the role of religious belief. By asking that creationism be given a place beside the theory of evolution, its supporters are asking that their beliefs be given equal standing with the scientific method. That violates the separation of church and state, as Judge Jones ruled; in claiming their science was not faith-based, he said, they lied.

What is surprising, as I watch “Inherit the Wind,” is how clearly Tracy’s Drummond/Darrow character defines the same argument and persuasively wins it. After his six expert scientific witnesses are not allowed to testify, he boldly calls Brady/Bryan onto the stand as a defense witness. The bombastic Brady is unable to refuse a chance to show off, and Drummond quizzes him on biblical details, more or less destroying his credibility in the process; Brady is finally reduced to agreeing with Bishop Usher that God created the Earth at exactly 9 a.m. on Oct. 23, 4004 BC. One might assume that calling Brady to the stand was a Hollywood gimmick, but no: Darrow really did bring Bryan to the stand and methodically ground him down.

“Inherit the Wind” is typical of the films produced and directed by Stanley Kramer (1913-2001), a liberal who made movies that had opinions and took stands. He was dismissed by some critics for saddling his films with pious messages, for preferring speeches to visual style and cinematic originality, but he stuck to his guns. Although his films like “On the Beach” (1959), “Judgment at Nuremberg” (1961), “Ship of Fools” (1965), “Guess Who's Coming to Dinner” (1967) and “Bless the Beasts and Children” (1971) took predictable positions on nuclear war, the Holocaust, interracial marriage and the preservation of species, they blended ideas and entertainment in a persuasive mixture. If his messages were predictable, they were also forthright; some of today’s message movies, for example the splendid “Syriana,” are so labyrinthine that viewers must sense the message almost by instinct.

Strange, that 46 years after it was made and 81 years after the Scopes trial, it is “Inherit the Wind” among all of Kramer’s films that seems most relevant and still generates controversy. Tracy’s character of Drummond in particularly seems boldly drawn. There are times when he seems to be veering toward a safe harbor on the religion-vs.-Darwin issue: “What goes on in this town is not necessarily the Christian religion,” he says, and one of the witnesses he is not allowed to call is a Christian minister who sees no conflict between evolution and his church.

But Drummond is unswerving in his emotional courtroom scenes, arguing that “fanaticism and ignorance is forever busy, and needs feeding.” When he is asked if he finds anything holy, he replies, “The individual human mind. In a child’s ability to master the multiplication table, there is more holiness than all your shouted hosannas and holy of holies.”

Note especially his final argument to the jury, which he performed in an unbroken shot. In the last scene of the film, Drummond stands in the empty courtroom, picks up a Bible in one hand and Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in the other, smiles, claps them together, and packs them both under his arm. How should we take this scene? Has he reconciled the two books, or does he think he’ll need them both for the appeal?