No, I never loved you Walter — not you or anybody else. I’m rotten to the heart. I used you, just as you said. That’s all you ever meant to me. Until a minute ago, when I couldn’t fire that second shot.

Is she kidding? Walter thinks so: “Sorry, baby. I’m not buying.” The puzzle of Billy Wilder‘s “Double Indemnity,” the enigma that keeps it new, is what these two people really think of one another. They strut through the routine of a noir murder plot, with the tough talk and the cold sex play. But they never seem to really like each other all that much, and they don’t seem that crazy about the money, either. What are they after?

Walter (Fred MacMurray) is Walter Neff (“two f’s–like in Philadelphia”). He’s an insurance salesman, successful but bored. The woman is Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), a lazy blond who met her current husband by nursing his wife–to death, according to her stepdaughter. Neff pays a call one day to renew her husband’s automobile insurance. He’s not at home, but she is, wrapped in a towel and standing at the top of a staircase. “I wanted to see her again,” Neff tells us. “Close, and without that silly staircase between us.”

The story was written in the 1930s by James M. Cain, the hard-boiled author ofThe Postman Always Rings Twice.A screenplay kicked around Hollywood, but the Hays Office nixed it for “hardening audience attitudes toward crime.” By 1944, Wilder thought he could film it. Cain wasn’t available, so he hired Raymond Chandler to do the screenplay. Chandler, whose novelThe Big SleepWilder loved, turned up drunk, smoked a smelly pipe, didn’t know anything about screenplay construction, but could put a nasty spin on dialogue.

Together they eliminated Cain’s complicated end-game and deepened the relationship between Neff and Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), the claims manager at the insurance company. They told the movie in flashback, narrated by Neff, who arrives at his office late at night, dripping blood, and recites into a Dictaphone. The voice-over worked so well that Wilder used it again in “Sunset Boulevard” (1950), which was narrated by a character who is already dead the first time he speaks. No problem; “Double Indemnity” originally ended with Neff in the gas chamber, but that scene was cut because an earlier one turned out to be the perfect way to close the film.

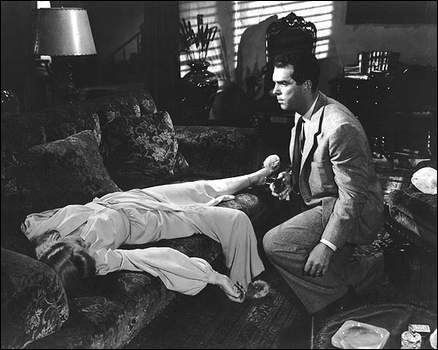

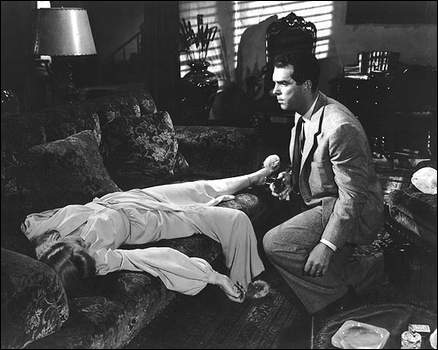

To describe the story is to miss the nuances that make it tantalizing. Phyllis wants Walter to sell her husband a $50,000 double indemnity policy, and then arrange the husband’s “accidental” death. Walter is willing, ostensibly because he’s fallen under her sexual spell. They perform a clever substitution. The husband, on crutches with a broken leg, is choked to death before a train ride. Taking his place, Neff gets on the train and jumps off. They leave the husband’s body on the tracks. Perfect. But later that night, going to the drugstore to establish an alibi, Neff remembers, “I couldn’t hear my own footsteps. It was the walk of a dead man.”

A clever crime. But why did they do it? Phyllis was bored and her husband had lost a lot of money in the oil business, so she had a motive. But it’s as if the idea of murder materialized only because Neff did — right there in her living room, talking about insurance. On their third meeting, after a lot of aggressive wordplay, they agree to kill the husband and collect the money. I guess they also make love; in 1944 movies you can’t be sure, but if they do, it’s only the once.

Why? Is Neff blinded by lust and greed? That’s the traditional reading of the film: weak man, strong woman. But he’s aloof, cold, hard, terse. He always calls her “baby,” as if she’s a brand, not a woman. His eyes are guarded and his posture reserved. He’s not moonstruck. And Phyllis? Cold, too. But later in the film she says she cares more about “them” than about the money. We can believe the husband died for money if they both seem driven by greed, but they’re not. We can believe he died because of their passion, but it seems more like a pretense, and fades away after the murder.

Standing back from the film and what it expects us to think, I see them engaged not in romance or theft, but in behavior. They’re intoxicated by their personal styles. Styles learned in the movies, and from radio and the detective magazines. It’s as if they were invented by Ben Hecht through his crime dialogue. Walter and Phyllis are pulp characters with little psychological depth, and that’s the way Billy Wilder wants it. His best films are sardonic comedies, and in this one, Phyllis and Walter play a bad joke on themselves.

More genuine emotion is centered elsewhere. It involves Neff’s fear of discovery, and his feelings for Keyes. Edward G. Robinson plays the inspector as a nonconformist who loosens his tie, reclines on the office couch, smokes cheap cigars, and wants to make Neff his assistant. He’s a father figure, or more. He’s also smart, and eventually he figures out that a crime was committed — and exactly how it was committed. His investigation leads to two scenes of queasy tension. One is when Keyes invites Neff to his office, and then calls in a witness who saw Neff on the train. Another is when Keyes calls unexpectedly at Neff’s apartment, when Neff expects Phyllis to arrive momentarily — and incriminatingly.

Does Keyes suspect Neff? You can’t really say. He arranges situations in which Neff’s guilt might be discovered, but they’re part of his routine techniques; perhaps only his subconscious, “the little man who lives in my stomach,” suspects Neff.

The end of the film is curious (it’s the beginning, too, so I’m not giving it away). Why does the wounded Neff go to the office and dictate a confession if he still presumably hopes to escape? Because he wants to be discovered by Keyes? Neff tells him, “You know why you couldn’t figure this one, Keyes? I’ll tell you. Because the guy you were looking for was too close — right across the desk from you.” Keyes says, “Closer than that, Walter,” and then Neff says, “I love you, too.” Neff has been lighting Keyes’ smokes all during the movie, and now Keyes lights Neff’s. You see why a gas chamber would have been superfluous.

Wilder’s “Double Indemnity” was one of the earlier films noir. The photography by John Seitz helped develop the noir style of sharp-edged shadows and shots, strange angles and lonely Edward Hopper settings. It’s the right fit for the hard urban atmosphere and dialogue created by Cain, Chandler, and the other writers Edmund Wilson called “the boys in the back room.”

“Double Indemnity” has one of the most familiar noir themes: The hero is not a criminal, but a weak man who is tempted and succumbs. In this “double” story, the woman and man tempt one another; neither would have acted alone. Both are attracted not so much by the crime as by the thrill of committing it with the other person. Love and money are pretenses. The husband’s death turns out to be their one-night stand.

Wilder, born in Austria in 1906, who arrived in America in 1933 and is still a Hollywood landmark, has an angle on stories like this. He doesn’t go for the obvious arc. He isn’t interested in the same things the characters are interested in. He wants to know what happens to them after they do what they think is so important. He doesn’t want truth, but consequences.

Few other directors have made so many films that were so taut, savvy, cynical and, in many different ways and tones, funny. After a start as a screenwriter, his directorial credits include “The Lost Weekend,” “Sunset Boulevard,” “Stalag 17,” “Sabrina,” “The Seven Year Itch,” “Witness for the Prosecution,” “Some Like It Hot,” “The Apartment” and “The Fortune Cookie.” I don’t like lists but I can’t stop typing. “Double Indemnity” was his third film as a director. That early in his career, he was already cocky enough to begin a thriller with the lines, “I killed him for money — and for a woman. I didn’t get the money. And I didn’t get the woman.” And end it with the hero saying “I love you, too” to Edward G. Robinson.