“Cat People” is constructed almost entirely out of fear. There wasn’t a budget for much of anything else. It exists on eight or nine sets, the running time is only 73 minutes, it has few special effects, there are no major stars, the violence is implied or dreaded but not much seen. Yet the film, made as a B picture for only $135,000, became RKO’s top grosser for 1942, bringing in $4 million, compared to the studio’s “Citizen Kane” at $500,000 in 1941. It renewed the careers of its producer Val Lewton, its director Jacques Tourneur and its star, the French actress Simone Simon; it inspired 10 more macabre titles from Lewton’s production unit and was copied all over Hollywood — because it was scary, and because it was cheap. What was hard to copy was its artistry.

“Cat People” wasn’t frightening like a slasher movie, using shocks and gore, but frightening in an eerie, mysterious way that was hard to define; the screen harbored unseen threats, and there was an undertone of sexual danger that was more ominous because it was never acted upon. Its heroine is a beautiful woman who never sleeps with her new husband (indeed she never even kisses him) because she fears that passion could turn her into a panther. The film magnifies her dread by exploiting the fear some people have of cats: They’re sneaky and devious and creep up on you, and are associated with Satan.

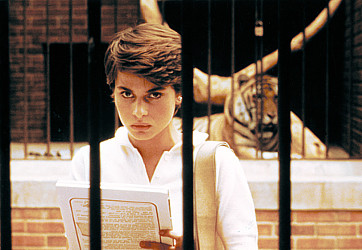

These dark undertones are framed by a story of everyday life. Irena (Simon) is sketching a panther at the zoo when she meets the clean-cut and well-behaved architect Oliver Reed (Kent Smith). He walks her home, she asks him in for tea, and they fall in love. She talks of her village in Serbia, of the belief that it sheltered satanic cultists who could take the form of cats. Good King John tried to kill these cat people, but some fled into the mountains, where they are said to live to this day. Irena secretly fears she is one of those people.

The dialogue, a first screenplay by DeWitt Bodeen, contains lines that hint at the bizarre and the erotic. Oliver tells Irena her perfume is “warm and living.” Irena says the roars of the big cats in the nearby zoo is “natural and soothing.” As the afternoon lengthens, she finally turns on a light, after saying she finds the dark “friendly.” Tourneur and his cinematographer, Nicholas Musuraca, who also worked together on the great film noir “Out of the Past,” are masters of light and shadow. They often place Irena in darkness, cast the silhouettes of other characters on the wall behind her, enclose her with shadows that work like a cage.

Irena and Oliver announce their engagement at a party in a restaurant, where an inexplicable and disturbing thing happens: She is approached by a strange woman (Elizabeth Russell), who affects a cat-like appearance and addresses her in Serbian, calling her “sister.” We never see this woman again, but her spectre haunts the movie. Are there lesbian notes in her approach to Irena? Perhaps in the sense that she is a powerful animal who challenges Oliver’s right to claim a mate?

In their marriage, Irena is fearful, and we understand that she is fearful of herself, of her latent evil. When the extraordinarily patient Oliver observes, “I’ve never kissed you,” Irena tells him: “I’ve lived in dread of this moment. I’ve never wanted to love you. I’ve stayed away from people … I’ve fled from the past. Some things you could never know, or understand — evil things.” Some of their conversations take place while he stands on one side of her bedroom door and she slumps against the other side.

He begins to work late at the office, where his co-worker Alice (Jane Randolph) is sympathetic. Irena follows him, sees them together, grows jealous, and one of the movie’s great sequences shows Alice walking home on a dark and deserted street, followed by footsteps. Nothing precisely happens to her, and we see little but some shadows and some disturbed leaves, but Alice is terrified when she jumps on a bus; she knows she saw something, which she will later describe to Oliver as Irena’s “cat form.” Her night walk seems to pass the same short span of stone wall again and again; Tourneur edits to make it seem longer. We are aware of the visual trick, yet it evokes a dreamlike quality.

Curiously, Alice, Irena and Oliver continue as friends, although there is a giveaway moment when they visit a museum together. As he suggests that Irena look at an upstairs exhibit, Oliver uses the word “we” to refer to himself and Alice, not Irena. This slip betrays him. Later that night, Alice goes for a plunge in the swimming pool at her residential club, and in a genuinely terrifying sequence she treads water in the deserted pool while … something … growls and paces, and then she screams. Notice how light reflected from the surface of the pool causes unsettling patterns to creep along the walls.

Irena has been seeing a psychiatrist. Dr. Judd (Tom Conway), a graduate of the Vincent Price school of therapy, talks to her while her face is detached in a circle of light surrounded by darkness. These sessions are not helpful, and she finds more relief by returning again and again to the leopard cage at the zoo. The genius of the film is in its indirection. It doesn’t specifically show us horrible things happening. It toys with us, introducing the elements from which horror could emerge. For example, Oliver gives Irena a kitten, which is terrified of her. Having established dark possibilities, “Cat People” gives us daylight scenes and chirpy supporting characters who don’t realize they’re skirting danger. At a pet shop run by a woman so cheerful she seems demented, they trade the cat for a canary. The destiny of this canary supplies, in a way, all we need to know about Irena’s fundamental nature. Yet she really does love Oliver — love him, and need him, as “the only friend I’ve ever had.” The film evokes the loneliness of the person set aside from humanity, given skills or powers that are a curse; it has the same kind of uneasy sympathy for Irena that Anne Rice has for her vampires. It’s not much fun, being a cat woman.

As a group, the films that Val Lewton produced in the 1940s are a landmark in American movie history. Born in the Ukraine, raised in Berlin, a newspaperman and pulp writer, he was a story editor for David O. Selznick before starting his own unit at RKO. Lewton (1904-1951) worked with directors who became important (Tourneur, Mark Robson, Robert Wise), but the films were and still are identified as his; I remember the French director Bertrand Tavernier and the American critic Manny Farber at the 1990 Telluride festival, talking about how unusual it was for a producer, not a director, to be the ruling auteur of a group of films.

Lewton may have found his overall approach by happenstance in “Cat People,” which began as a title without a story and developed its minimalist style as a result of the low budget. But he and Tourneur had found a note that worked, and in various ways Lewton found it again in such films as “I Walked with a Zombie” (1943), “The Leopard Man” (1943), “The Curse of the Cat People” (1944) and “The Body Snatcher” (1945). He made “movies that are often more like symbolist poems or obscure fetishistic rituals,” wrote Geoffrey O’Brien in the New York Review of Books. “They are not so much frightening as unnervingly strange and shot through with a palpable melancholy.”

Do the movies still work today, or are they too quiet? Depends on your tastes. Paul Schrader made a much more specific version of “Cat People” in 1982, which I admired for its own qualities, including the use of atmospheric New Orleans locations. But the 1942 movie gets under your skin. There is something subtly alarming about the oddly mannered good-girl behavior of Simone Simon, and the unearthly detachment of Kent Smith as her husband, and the rooms and streets that look not like places but like ideas of places. And something touching about Irena, who has never had a friend, and fears she will kill the only person she loves, and is told she is insane. At the end, Oliver pays her a simple tribute: “She never lied to us.”

The new bookIcons of Grief,by Alexander Nemerov, is a study of Val Lewton’s career. See also the Great Movie review of Tourneur’s “Out of the Past.”