“Beauty in life may come from makeup, or what have you, but in death, you have to fall back on character.”

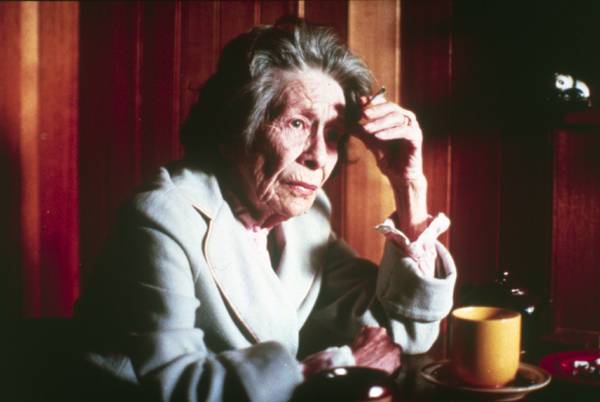

The old woman has just come from attending a funeral and knows her own is not far in the future. She is speaking with the young nurse who visits her daily. The actress, Sheila Florance, could be describing herself. She is bone thin, her arms like sticks, her face deeply lined. She was once a great beauty, but now what she has left is character.

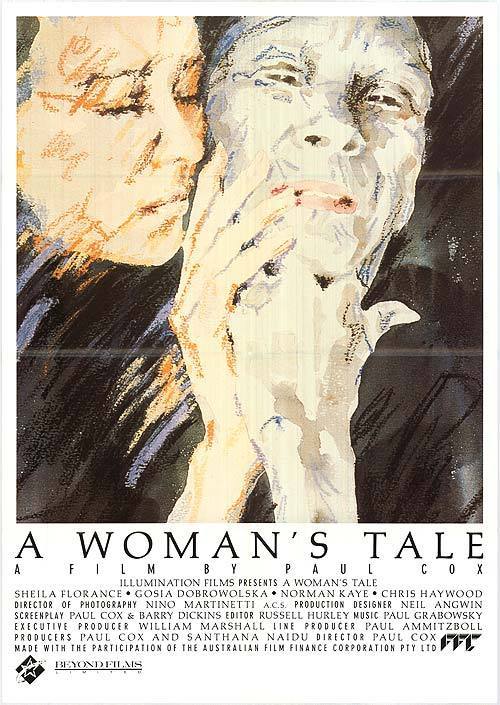

Paul Cox‘s “A Woman’s Tale” (1991) tells the honest, brave and profoundly touching story of the last days of a 78-year-old woman named Martha (Florance), who lives with her memories and treasured possessions in a few rooms in a Melbourne rental complex and defiantly guards her independence. She knows she is dying and has shrugged off the last course of cancer treatment. She is in pain, but doesn’t complain, and spends her days taking care of others: Billy, her senile neighbor, surrounded by his memories of the war; Miss Inchley, a sweet old lady as innocent as Martha is knowing; and even, in a way, her nurse Anna (Gosia Dobrowolska).

The movie looks calmly and with love at the fact that life ends. It provides not one of those sentimental Hollywood deaths, poetic and composed, but a portrait of a woman who faces her decline with fierce pride. Florance herself was dying when the movie was made, knew it and died a few days after winning an Australian Academy Award as best actress in 1991.

She was a grande dame of the Australian theater, a friend of Paul Cox’s since the 1970s, and the film plays like her final testament — not least since some of Martha’s memories are actually her own. She describes an aerial dogfight during the Battle of Britain, and it becomes immediate for us: The lumbering German bombers, the little Spitfires appearing out of nowhere, the noise! the noise! of the roaring engines and the guns and the explosions, and the shreds of airplane and body parts raining down on those below.

Martha is very ill, but gets around. She helps poor Billy (Norman Kaye), who is forever locking himself out of his room or wetting his pajamas. She is a good companion for Miss Inchley, who is 90, taking her for walks in the park, where they chat with Martha’s friend, the local prostitute. (“Do you know what a whore is, Miss Inchley?” “Isn’t that a rude word?” “Yes, it is.”) Martha’s nights are sleepless, and she passes them with her cigarettes and her cat, Sam, listening to talk radio. When a suicidal 16-year-old girl phones in, Martha calls to speak with her, to tell her how much there is to live for.

Martha’s son, Jonathan (Chris Haywood), cares for her, but is very busy and has a wife who has long since fallen out with Martha. Jonathan thinks his mother would be better off in a nursing home. “Do you know how hard we work to keep these people out of homes?” asks the nurse Anna. She fights for Martha’s independence because she respects it; she loves the old woman and has become like her daughter. Martha, in turn, lets Anna use her bedroom for an affair the nurse is having with a married man. “I’m going to die in this bed,” she says, “and I want you to love in it.”

Billy has a daughter, who never visits him. “We saw him at Christmas,” the daughter tells Martha. “That was the one day we didn’t see him,” Martha replies tartly. She is a woman of power and confidence, a woman who insists on her dignity when the world wants her to give up and admit she is sick and go off somewhere convenient to die.

What a feisty defense she makes of her cigarettes in a no-smoking restaurant! She hides the worst of her pain from everyone, but we see her wracked with agonizing spells of coughing. In a scene of extraordinary courage, Cox and Florance show us Martha naked in her bath, her body pitifully gaunt, her mouth that must once have been so sensuous, now without lipstick, an anguished slash in a wrinkled face.

Her memories are of the war, when she was in Britain. “In Bristol,” she tells Anna, “my 10-month-old baby was killed. A German dropped a bomb, and her lungs exploded.” There is a nightmare in which she wanders in a wood, and restless dreams of falling water. She visits a waterfall with Miss Inchley and observes how the water seems to pause for a moment at the precipice, before disintegrating into exploding, falling drops, only to reassemble at the bottom as if nothing had happened. Is that what happens when we die? “A Woman’s Tale” is too realistic and tactful to make such a greeting card statement; it allows us to conclude what we will about Martha and her story.

The performance by Dobrowolska is essential to the film’s impact. We see that she is efficient, a good visiting nurse, but that isn’t the point. The point is that she loves and admires Martha and will fight for her, and Dobrowolska brings a natural, unforced sweetness and tenderness to the role. “How I envy your youth!” Martha says, and Anna smiles and says, “I’m not that young.” Ah, but she is, and Martha tells her, “Life is so beautiful. Keep love alive.”

Anna visits old Billy every day, and one day Billy’s hand touches her cheek and then falls slowly toward her breast. Anna removes it, and tells Martha, “Billy tried to touch my breast.” “Oh, dear, why didn’t you let him?” Martha says. “What difference does it make?” This conversation results in a later scene that is sweet, sad and quietly moving.

When I say that Florance’s performance is courageous, I do not mean simply that she made the movie even though she was dying. That took strength and resolve, but what takes courage is to reveal her character as she does, to let us see Martha stripped of vanity. All women, actresses especially, want to look their best; Florance shares her frail body with us like a sacrament.

The character’s vanity, we realize, is expressed not through her appearance, but through her independence, through her determination to fight through every day without giving up and going off to an institution to die. That she cares for Billy and Anna and Miss Inchley and the girl on the talk radio is her reason for holding on: She can still be of use, and that’s worth living for.

Paul Cox is one of the heroes of modern cinema, a Dutch-born Australian who makes his way independently of the mainstream production and distribution channels. In a world of fiercely marketed product and manufactured cinematic artifacts, his films embrace all the wonder and complexity of everyday human life. Consider his “Man of Flowers” (1983), also starring Norman Kaye (who is in most of his films), as a particular and eccentric man who lives alone, and pays for sex in a way that, once we understand it, becomes touching (to know all helps us to forgive). Or his “Vincent” (1987), one of the best documentaries ever made about an artist, and his “Diaries of Vaslav Nijinsky” (2001), an almost surreal effort to penetrate the mind of the great dancer. Or his wonderful “Innocence” (2000), with its evocation of a romance that begins between two teenagers and continues when they meet again in old age.

His new film, “The Human Touch,” played at Cannes 2004. It deals with a love affair, but a very particular one, between an uneasily married woman and a brilliant older man who is impotent, but whose caresses excite her as never before. All well and good, but who but Cox would think to transport his characters from Australia to France, and send them into a cave that is 110 million years old, where they are awed by the distance between their brief lives and lusts and the overwhelming span of time that humbles them? Directors like Cox validate the cinema in an age of commercialism; his struggle to carry on making his films his way shows the same kind of courage that Martha has in “A Woman’s Tale.” He knows he can be of use.

Both “A Woman’s Tale” and “Innocence” were selections at my Overlooked Film Festival. Reviews of five Paul Cox films are online at rogerebert.com