Yes, but what is Godard trying to say?

This is the question, the question, the question critics ask, and have asked, since Jean Luc-Godard made his first feature, “Breathless,” back in 1959. And with his latest, “Goodbye to Language,” they’re asking it again.

What is it? Where to begin? Much of the film is built around a young couple at a lake house who do a lot of arguing and also spend a lot of time naked. (Much of this feels like a self-parody of European art cinema tendencies: How can I get people to sit still for an extended discussion of politics and language? By having attractive people take their clothes off, of course.) But these characters one just anchor points for, essentially, a feature length montage, much of it quickly edited, with few shots held longer than three or four seconds. The style might be irritating in a traditional narrative film. But it seems of a piece in a movie that is partly about (Godard’s films are always “about” more than one thing—and often only partly about any of them) the impossibility of focusing, concentrating, and comprehending history, and politics, and the written and spoken word, then making all of it make some kind of sense, if only to yourself. If Terrence Malick tried to make a Godard film in the spirit of Godard, it might look something like this, though with less prolonged discussion of Hitler, the Holocaust, colonialism, imperialism and other favorite Godard subjects, but with Godard’s cryptic voice-over aphorisms (“This morning is a dream. Each person must think that the other is the dreamer”).

Did I mention it’s in 3-D? It’s in 3-D. And Godard’s use of 3-D is the most original since Werner Herzog’s “The Cave of Forgotten Dreams.” Herzog’s brilliance was counterintuitive (at least from a commercial standpoint). He put a technical process that’s often deployed in service of spectacle and violence and instead used it in the most mundane (and therefore revelatory) manner: to give an added sense of presence, of “you are there-ness,” to very long takes, of a camera gliding through plant life (a snake’s-eye view) or an unseen viewer (us) scrutinizing an ancient mural, or listening to an expert tell us about that mural while shifting nervously from foot to foot.

Godard deploys the technology in a cheeky way (of course he does; he’s Godard!). Here, 3-D becomes one more element in Godard’s career-long fascination with exploring cinema’s formal properties, its grammar and technique and technology—the better to show how films can tell or elide a story, reveal or obfuscate the truth, or just kill screen time by distracting us with pretty pictures or jokes. There are a lot of pretty pictures in this movie, and a lot of jokes, and they’re not all corrosive or politically minded. Sometimes Godard seems to just be doing them because he wants to do them—because he wants to try something new, or different. Other times the film combines pretty pictures and jokes to create an oxymoron: a gorgeous sight gag.

The film often superimposes two titles or subtitles over each other, collage-style, or allows people or objects in the frame to partly obscure written words; at a New York screening of “Goodbye to Language” a few weeks back, the first time the film played around with text in this way, you could see a few critics sort of leaning to one side, as if attempting to see around whatever was on top of the thing that they wanted to see. The movie also uses 3-D to create something like 2 1/2 D, by which I mean, you’re aware of separate planes within the same image, seemingly separated by indeterminate space, yet each plane is two-dimensional, which means the net effect is like looking through a series of scrims, each emblazoned with a silkscreened image. (Godard has contributed episodes to two 3-D anthology films, “The Three Disasters” and “The Bridges of Sarajevo.” Clearly this format is not just a lark to him.)

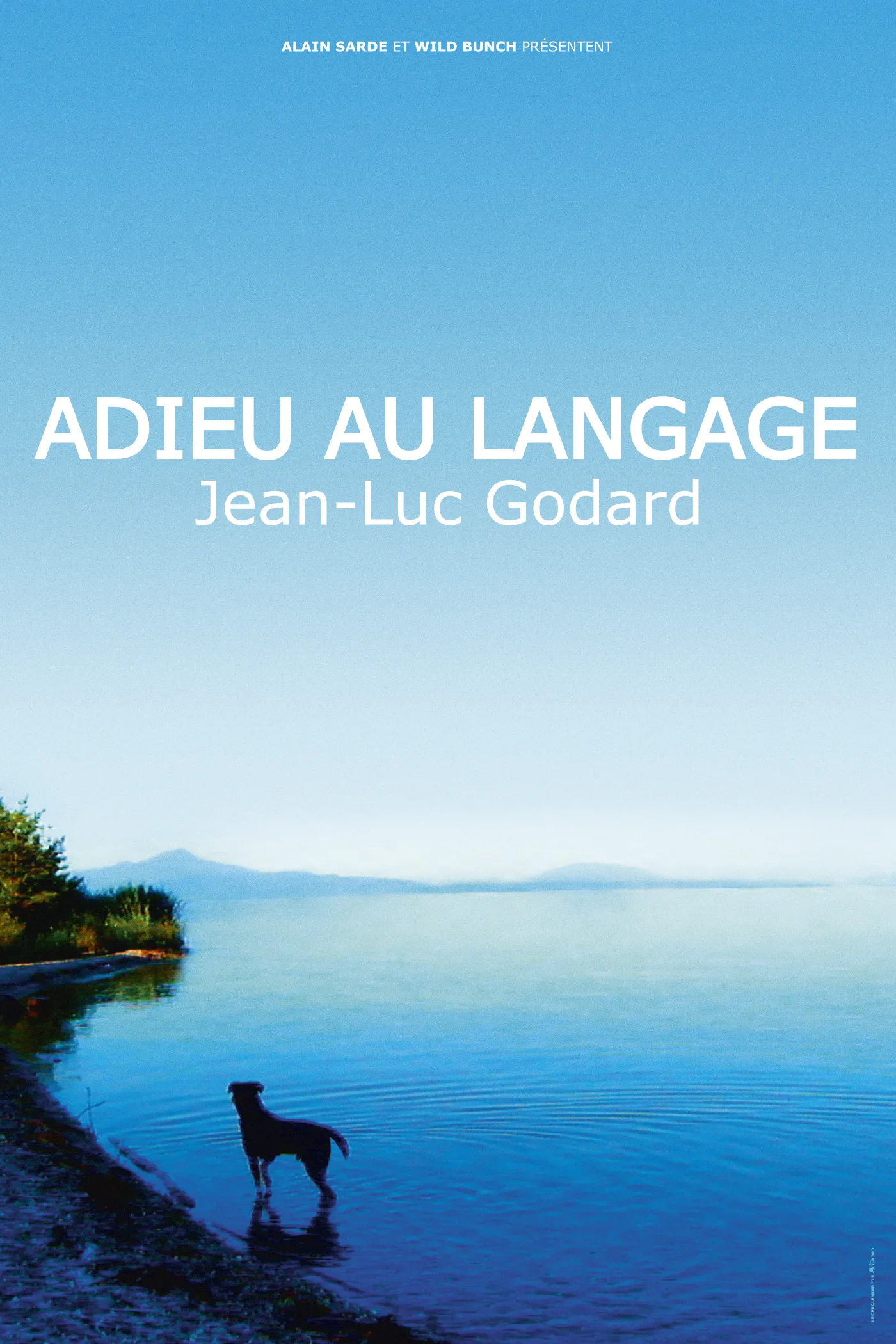

Shooting in digital video again, the 83-year old director plays with color saturation, exposure, light and shadow. In shots taken through the windshield of a car zipping down a highway at night, the blacks have been crushed so that you can’t see any background detail; red taillights in the background become splashes of red. In a shot of roses in a green field, the red of the flowers has been cranked up so that the color smears and seems to be trying to escape the petals, like spirits escaping a body. An intriguingly Malick-ian point-of-view shot looking up at trees festooned with fall leaves favors two colors: orange for the leaves and violet for the sky. And of course there are lots and lots and lots of shots of dogs. Godard loves dogs.

Meanwhile the film’s multiple narrators go full-steam ahead, peppering the soundtrack with thoughts and fragments of thoughts, some of them overlapping. Some music cues are cut off abruptly, as if somebody had pressed the “Stop” button on a recording. We hear that cinema is the enemy and savior of memory, that the state is at war with its people. The camera lingers over a shot of a sink superimposed over a shot of bisected oranges and lemons superimposed over a red substance (blood) slowly spreading through water.

The film continually circles back to its rhetorical center—the idea that existence is about trying to reconcile the “real” world with the subjective experience of the world, and the names and notions we use to catalog and define the world—but the digressions are what make it sing, or scat-sing. “I will barely say a word,” says a voice on the soundtrack—maybe Godard?—adding, “I am looking for poverty in language.” Given that the film is itself so richly expressive in every sort of language (written, spoken, visual) this seems like yet another wonderful joke, one that somehow doubles as a lament. “Goodbye to Language” will be catnip to anyone who continues to appreciate Godard and find him fascinating, and toxic to anyone who read this review and thought, “No thanks.” It’s a rapturous experience, mostly, though tempered by a certain Godardian crankiness. Watching it is, I would imagine, as close as we’ll get to being able to be Godard, sitting there thinking, or dreaming. It’s a documentary of a restless mind.