The film is set in the next century, when humans coexist with cyborgs, who are part human, part machine and part computer. The Puppet Master describes itself as “a living, thinking entity who was created in the sea of information.” It once occupied a “real” body but was tricked into diving into a cyborg, and then its body was murdered. Now it exists only in the electronic universe, but is in search of another body to occupy — or share.

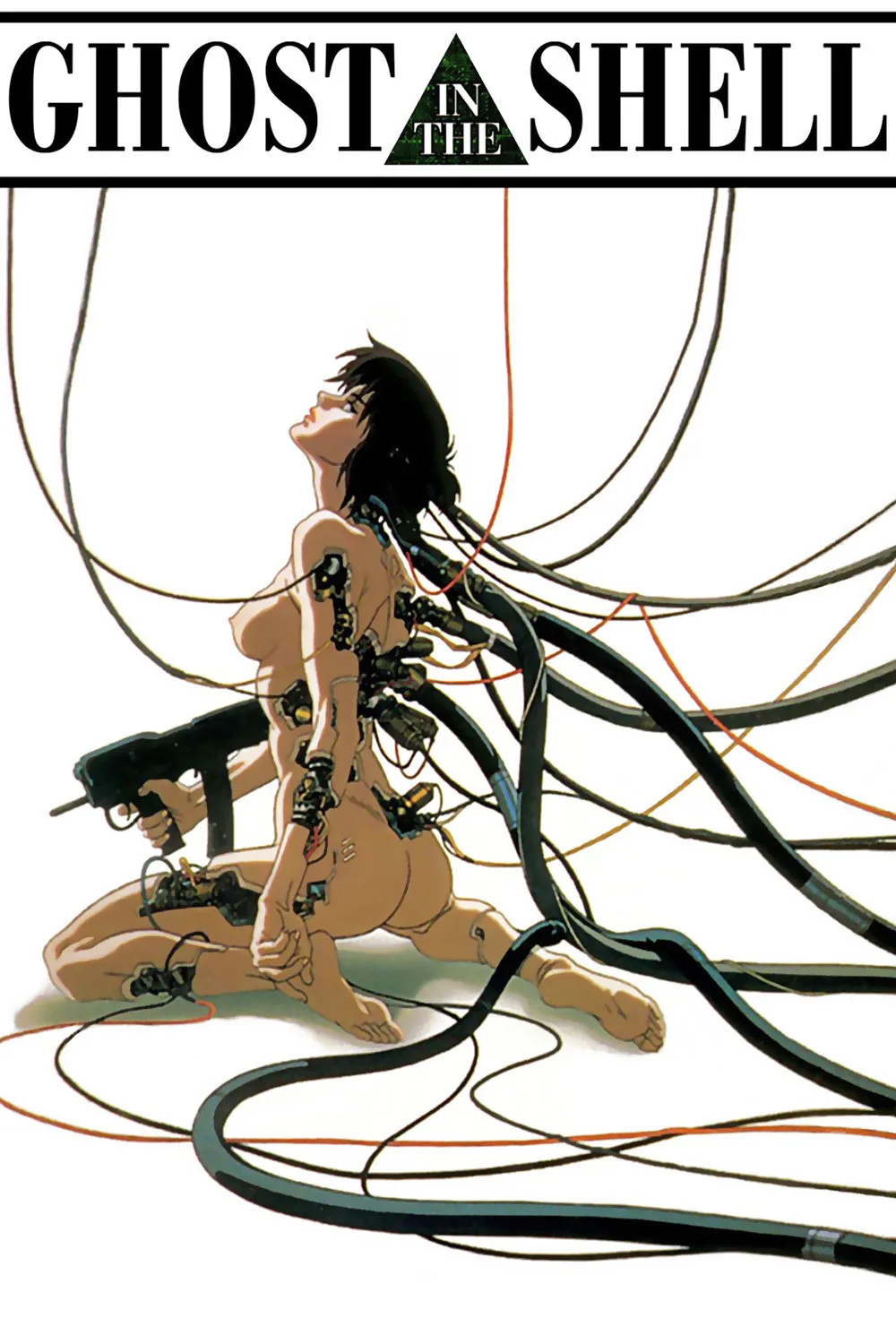

“Ghost in the Shell” is not in any sense an animated film for children. Filled with sex, violence and nudity (although all rather stylized),it’s another example of anime, animation from Japan aimed at adults–in this case, the same college-age audience that reads Heavy Metal and other slick comic zines. Anime has been huge in Japan for years but is now making inroads into the world market; this film was co-produced with British money and includes a song performed by U2, “One Minute Warning,” which runs nearly five minutes under apocalyptic images.

The movie has a tendency, as does a lot of traditional science fiction, for its characters to talk in concepts and abstract information. Sample dialogue: “Aside from a slight brain augmentation, your body’s almost entirely human.” Or, “If a cyber could create its own ghost, what would be the purpose of being human?” Or (my favorite), “You’re treated like other humans, so stop with the angst!”

The lead character is a shapely woman named Maj. Motoko Kusanagi, a cyborg who runs an intelligence operation. Her unit is assigned to investigate an evil foreign operative who wants political asylum, but soon the case leads to contact with the Puppet Master, the “most dreaded cyber-criminal of all time. ”The major and other characters can change shapes, become invisible and dive into the minds of others–which places them not so much in the future as in the tradition of Japanese fantasy, in which ghosts have always been able to do such things.

There is much moody talk in the movie about what it is to be human. All of the information accumulated in a lifetime, we learn, is less than a drop in the ocean of information, and perhaps a creature that can collect more information and hold onto it longer is … more than human. In describing this vision of an evolving intelligence, Corinthians is evoked twice: “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as I am known.” At the end of the film, Puppet Master invites the major to join it face to face in its brave new informational sea.

The movie uses the film noir visuals that are common in anime, and it hares that peculiar tendency of all adult animation to give us women who are(a) strong protagonists at the center of the story, and (b) nevertheless almost continuously nude. An article about anime in a recent issue of Film Quarterly suggests that to be a “salary man” in modern Japan is so exhausting and dehumanizing that many men (who form the largest part of the animation audience)project both freedom and power onto women, and identify with them as fictional characters. That would help explain another recent Japanese phenomenon, the fad among (straight) teenage boys of dressing like girls.

“Ghost in the Shell” is intended as a breakthrough film, aimed at theatrical release instead of a life on tape, disc and campus film societies.

The ghost of anime can be seen here trying to dive into the shell of the movie mainstream. But this particular film is too complex and murky to reach a large audience, I suspect; it’s not until the second hour that the story begins to reveal its meaning. But I enjoyed its visuals, its evocative soundtrack (including a suite for percussion and heavy breathing), and its ideas.