Werner Herzog‘s “Fitzcarraldo”is a movie in the great tradition of grandiose cinematic visions. Like Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” or Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” it is a quest film in which the hero’s quest is scarcely more mad than the filmmaker’s. Movies like this exist on a plane apart from ordinary films. There is a sense in which “Fitzcarraldo” is not altogether successful — it is too long, we could say, or too meandering — but it is still a film that I would not have missed for the world.

The movie is the story of a dreamer named Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, whose name has been simplified to “Fitzcarraldo” by the Indians and Spanish who inhabit his godforsaken corner of South America. He loves opera. He spends his days making a little money from an ice factory and his nights dreaming up new schemes. One of them, a plan to build a railroad across the continent, has already failed. Now he is ready with another: He seriously intends to build an opera house in the rain jungle, twelve hundred miles upstream from the civilized coast, and to bring Enrico Caruso there to sing an opera.

If his plan is mad, his method for carrying it out is madness of another dimension. Looking at the map, he becomes obsessed with the fact that a nearby river system offers access to hundreds of thousands of square miles of potential trading customers — if only a modern steamship could be introduced into that system. There is a point, he notices, where the other river is separated only by a thin finger of land from a river that already is navigated by boats. His inspiration: Drag a steamship across land to the other river, float it, set up a thriving trade, and use the profits to build the opera house — and then bring in Caruso! This scheme is so unlikely that perhaps we should not be surprised that Herzog’s story is based on the case of a real Irish entrepreneur who tried to do exactly that.

The historical Irishman was at least wise enough to disassemble his boat before carting it across land. In Herzog’s movie, however, Fitzcarraldo determines to drag the boat up one hill and down the other side in one piece. He enlists engineers to devise a system of blocks-and-pulleys that will do the trick, and he hires the local Indians to work the levers with their own muscle power. And it is here that we arrive at the thing about “Fitzcarraldo” that transcends all understanding: Werner Herzog determined to literally drag a real steamship up a real hill, using real tackle and hiring the local Indians! To produce the movie, he decided to do personally what even the original Fitzgerald never attempted.

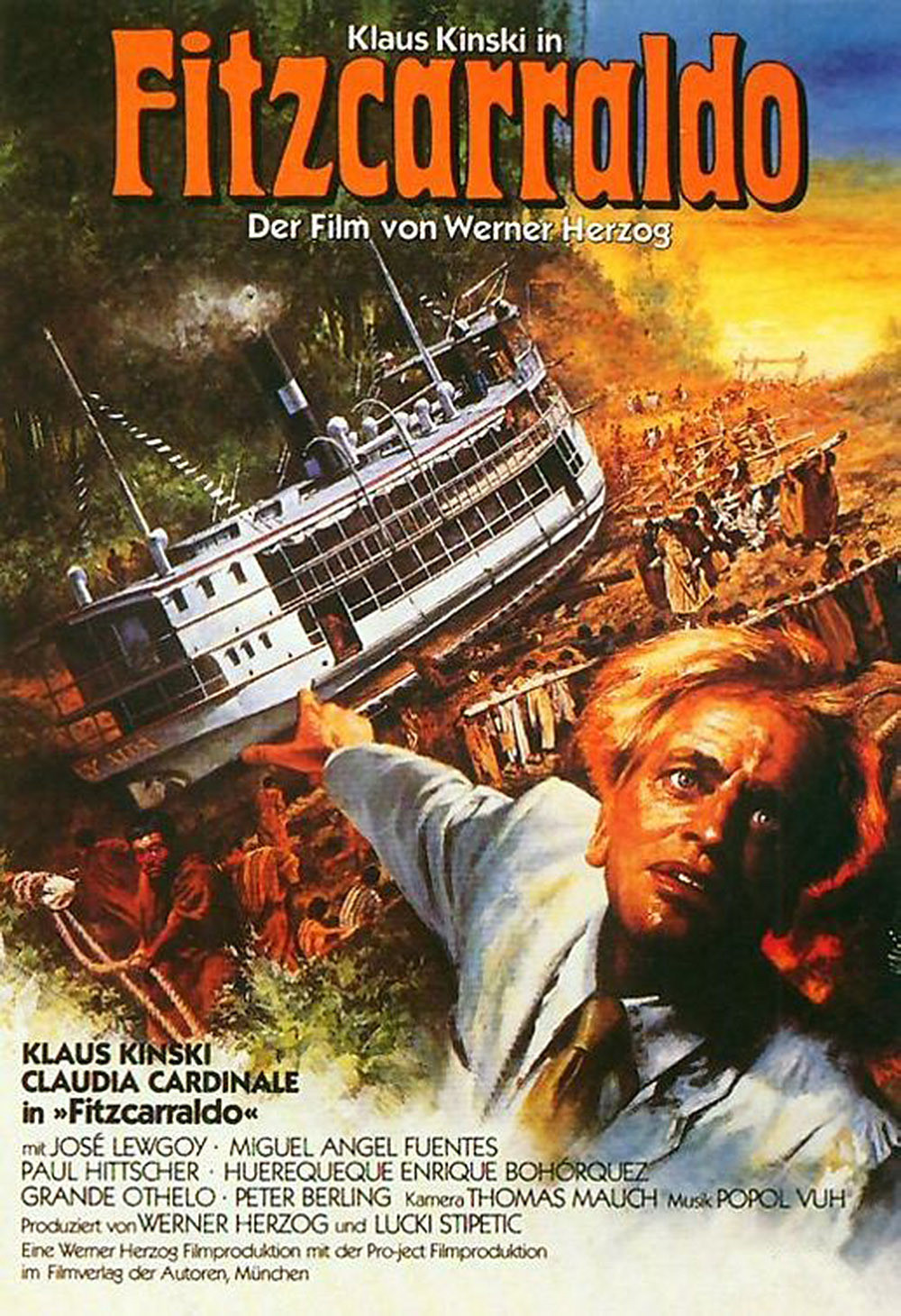

Herzog finally settled on the right actor to play Fitzcarraldo, author of this plan: Klaus Kinski, the shock-haired German who starred in Herzog’s “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” and “Nosferatu,” is back again to mastermind the effort. Kinski is perfectly cast. Herzog’s original choice for the role was Jason Robards, who is also gifted at conveying a consuming passion, but Kinski, wild-eyed and ferocious, consumes the screen. There are other characters important to the story, especially Claudia Cardinale as the madam who loves Fitzcarraldo and helps finance his attempt, but without Kinski at the core it’s doubtful this story would work.

The story of Herzog’s own production is itself well-known, and has been told in Les Blank’s “Burden of Dreams,” a brilliant documentary about the filming. It’s possible that every moment of “Fitzcarraldo” is colored by our knowledge that Herzog was “really” doing the things we see Fitzcarraldo do. (The movie uses no special effects, no models, no opticals, no miniatures.) Perhaps we’re even tempted to give the movie extra points because of Herzog’s ordeal in the jungle.

But “Fitzcarraldo” is not all sweat and madness. It contains great poetic images of the sort Herzog is famous for: An old phonograph playing a Caruso record on the deck of a boat spinning out of control into a rapids; Fitzcarraldo frantically oaring a little rowboat down a jungle river to be in time to hear an opera; and of course the immensely impressive sight of that actual steamship, resting halfway up a hillside.

“Fitzcarraldo” is not a perfect movie, and it never comes together into a unified statement. It is meandering, and it is slow and formless at times. Perhaps the conception was just too large for Herzog to shape. The movie does not approach perfection as “Aguirre” did. But as a document of a quest and a dream, and as the record of man’s audacity and foolish, visionary heroism, there has never been another movie like it.