The Driver drives for hire. He has no other name, and no other life. When we first see him, he’s the wheelman for a getaway car, who runs from police pursuit not only by using sheer speed and muscle, but by coolly exploiting the street terrain and outsmarting his pursuers. By day, he is a stunt driver for action movies. The two jobs represent no conflict for him: He drives.

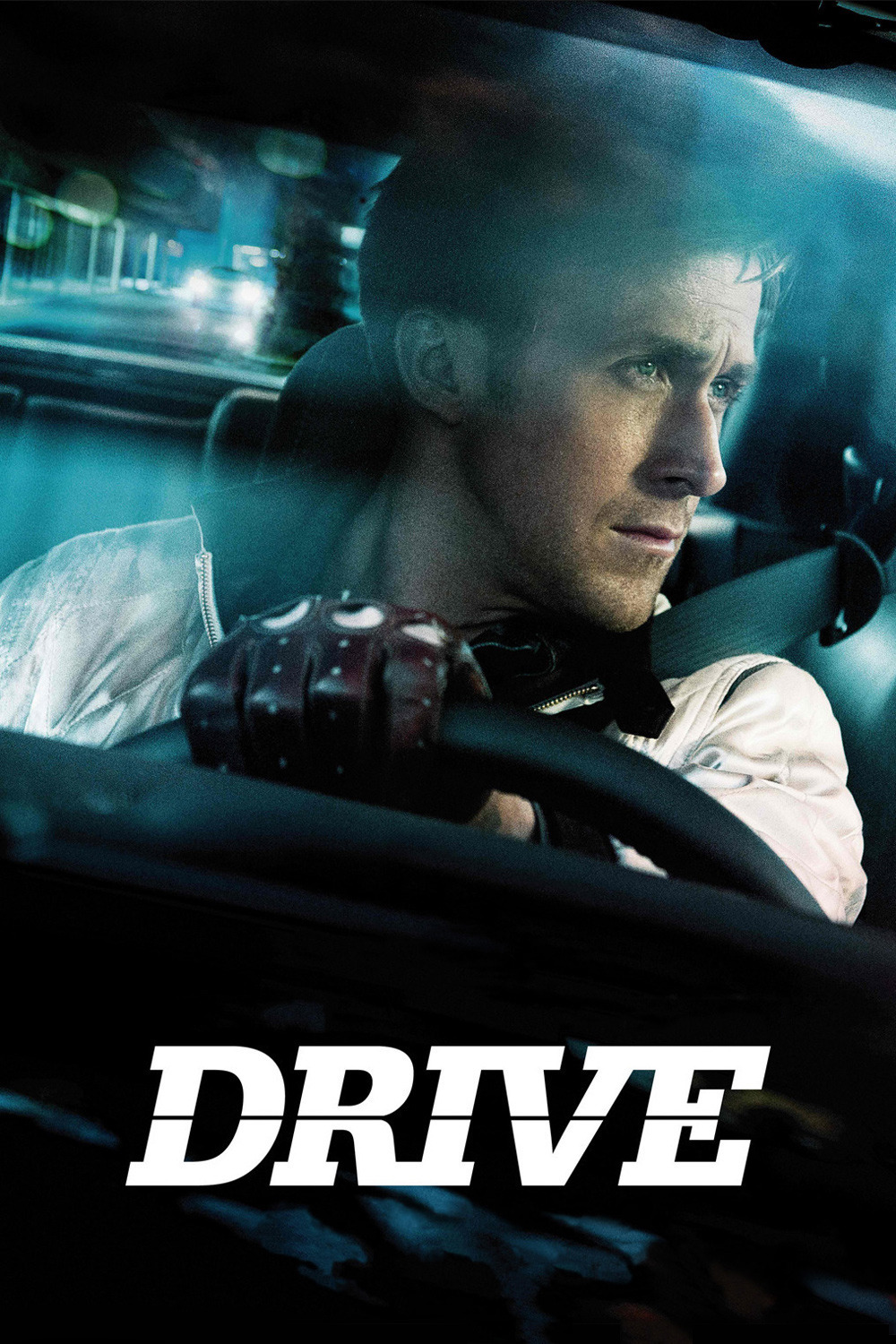

As played by Ryan Gosling, he is in the tradition of two iconic heroes of the 1960s: Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name and Alain Delon in “Le Samourai.” He has no family, no history and seemingly few emotions. Whatever happened to him drove any personality deep beneath the surface. He is an existential hero, I suppose, defined entirely by his behavior.

That would qualify him as the hero of a mindless action picture, all CGI and crashes and mayhem. “Drive” is more of an elegant exercise in style, and its emotions may be hidden but they run deep. Sometimes a movie will make a greater impact by not trying too hard. The enigma of the driver is surrounded by a rich gallery of supporting actors who are clear about their hopes and fears, and who have either reached an accommodation with the Driver, or not. Here is still another illustration of the old Hollywood noir principle that a movie lives its life not through its hero, but within its shadows.

The Driver lives somewhere (somehow that’s improbable, since we expect him to descend full-blown into the story). His neighbor is Irene, played by Carey Mulligan, that template of vulnerability. She has a young son, Benecio (Kaden Leos), who seems to stir the Driver’s affection, although he isn’t the effusive type. They grow warm, but in a week, her husband, Standard (Oscar Isaac), is released from prison. Against our expectations, Standard isn’t jealous or hostile about the new neighbor, but sizes him up, sees a professional and quickly pitches a $1 million heist idea. That will provide the engine for the rest of the story, and as Irene and Benecio are endangered, the Driver reveals deep feelings and loyalties indeed, and undergoes enormous risk at little necessary benefit to himself.

The film by the Danish director Nicolas Winding Refn (“Bronson“), based on a novel by James Sallis, peoples its story with characters who bring lifetimes onto the screen, in contrast to the Driver, who brings as little as possible. Ron Perlman seems to be a big-time operator working out of a small-time front, a pizzeria in a strip mall. Albert Brooks, not the slightest bit funny, plays a producer of the kinds of B movies the Driver does stunt driving for — and also has a sideline in crime. These people are ruthless.

More benign is Bryan Cranston, as the kind of man you know the Driver must have behind him, a genius at auto repairs, restoration and supercharging.

I mentioned CGI earlier. “Drive” seems to have little of it. Most of the stunt driving looks real to me, with cars of weight and heft, rather than animated impossible fantasies. The entire film, in fact, seems much more real than the usual action-crime-chase concoctions we’ve grown tired of. Here is a movie with respect for writing, acting and craft. It has respect for knowledgable moviegoers. There were moments when I was reminded of “Bullitt,” which was so much better than the films it inspired. The key thing you want to feel, during a chase scene, is involvement in the purpose of the chase. You have to care. Too often we’re simply witnessing technology.

Maybe there was another reason I thought of “Bullitt.” Ryan Gosling is a charismatic actor, as Steve McQueen was. He embodies presence and sincerity. Ever since his chilling young Jewish neo-Nazi in “The Believer” (2001), he has shown a gift for finding arresting, powerful characters. An actor who can fall in love with a love doll and make us believe it, as he did in “Lars and the Real Girl” (2007), can achieve just about anything. “Drive” looks like one kind of movie in the ads, and it is that kind of movie. It is also a rebuke to most of the movies it looks like.