“Downfall” takes place almost entirely inside the bunker beneath Berlin where Adolf Hitler and his inner circle spent their final days, and died. It ventures outside only to show the collapse of the Nazi defense of Berlin, the misery of the civilian population and the burning of the bodies of Hitler, Eva Braun, and Joseph and Magda Goebbels. For the rest, it occupies a labyrinth of concrete corridors, harshly lighted, with a constant passage back and forth of aides, servants, guards, family members and Hitler’s dog, Blondi. I was reminded, oddly, of the claustrophobic sets built for “Das Boot,” which took place mostly inside a Nazi submarine.

Our entry to this sealed world is Traudl Junge (Alexandra Maria Lara), hired by Hitler as a secretary in 1942 and eyewitness to Hitler’s decay in body and mind. She wrote a memoir about her experiences, which is one of the sources of this film, and “Blind Spot” (2002) was a documentary about her memories. In a clip at the end of “Downfall,” filmed shortly before her death, she says she now feels she should have known more than she did about the crimes of the Nazis. But like many secretaries the world over, she was awed by the power of her employer and not included in the information loop. Yet she could see, as anyone could see, that Hitler was a lunatic. Sometimes kind, sometimes considerate, sometimes screaming in fits of rage, but certainly cut loose from reality.

Against the overarching facts of his personal magnetism and the blind loyalty of his lieutenants, the movie observes the workings of the world within the bunker. All power flowed from Hitler. He was evil, mad, ill, but long after Hitler’s war was lost he continued to wage it in fantasy. Pounding on maps, screaming ultimatums, he moved troops that no longer existed, issued orders to commanders who were dead, counted on rescue from imaginary armies.

That he was unhinged did not much affect the decisions of acolytes like Joseph and Magda Goebbels, who decided to stay with him, and commit suicide as he would. “I do not want to live in a world without National Socialism,” says Frau Goebbels, and she doesn’t want her six children to live in one, either. In a sad, sickening scene, she gives them all a sleeping potion and then, one by one, inserts a cyanide capsule in their mouths and forces their jaws closed with a soft but audible crunch. Her oldest daughter, Helga, senses there is something wrong; senses, possibly, she is being murdered. Then Magda sits down to a game of solitaire before she and Joseph kill themselves. (By contrast, Heinrich Himmler wonders aloud, “When I meet Eisenhower, should I give the Nazi salute, or shake his hand?”)

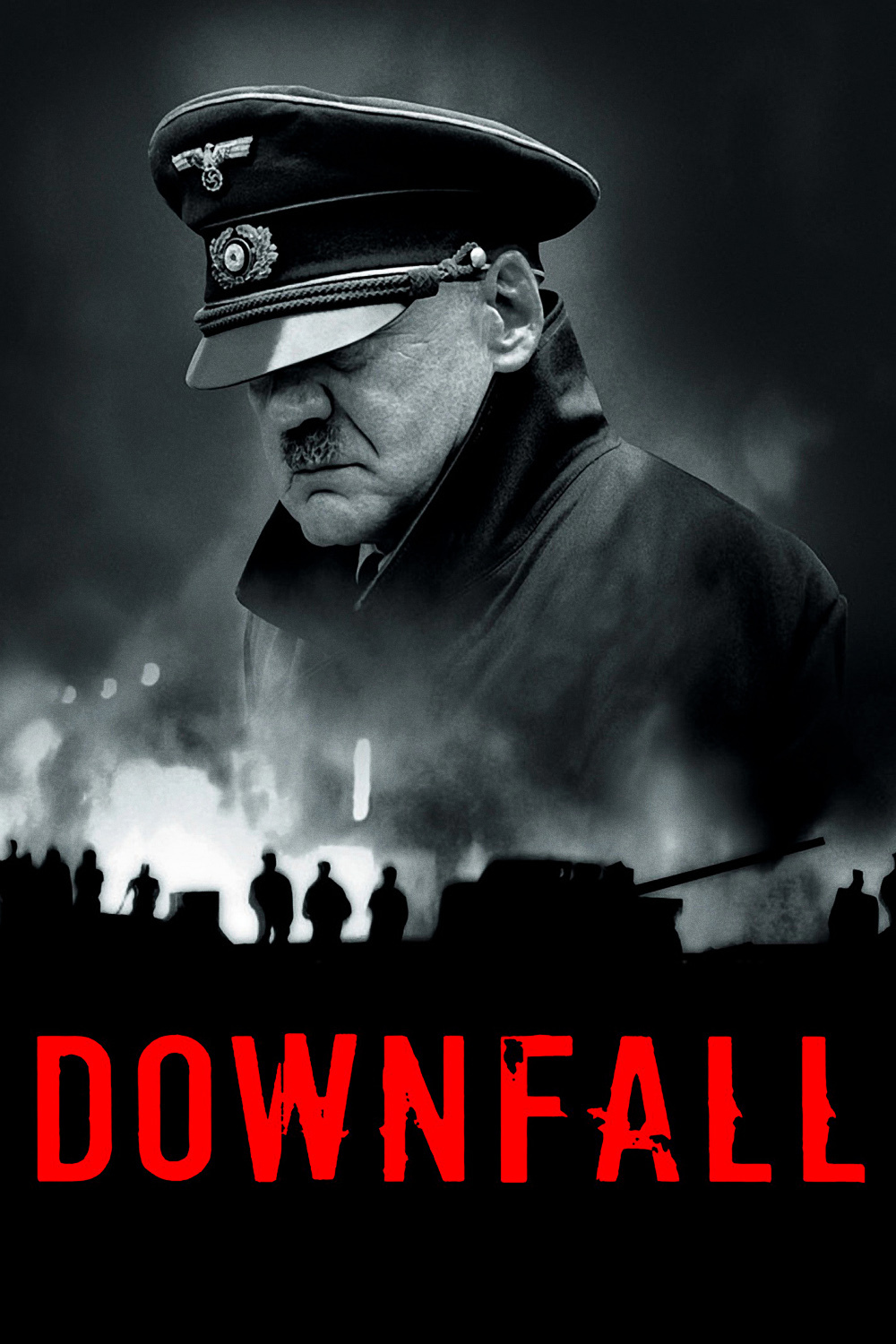

Hitler is played by Bruno Ganz, the gentle soul of “Wings of Desire,” the sad-eyed romantic or weary idealist of many roles over 30 years. Here we do not recognize him at first, hunched over, shrunken, his injured left hand fluttering behind his back like a trapped bird. If it were not for the 1942 scenes in which he hires Frau Junge as a secretary, we would not be able to picture him standing upright. He uses his hands as claws that crawl over battlefield maps, as he assures his generals that this or that impossible event will save them. And if not, well: “If the war is lost, it is immaterial if the German people survive. I will shed not one tear for them.” It was his war, and they had let him down, he screams: betrayed him, lied to him, turned traitor.

Frau Junge and two other secretaries bunk in a small concrete room, and sneak away to smoke cigarettes, which Hitler cannot abide. Acting as a hostess to the death watch, his mistress Eva Braun (Juliane Kohler) presides over meals set with fine china and crystal. She hardly seems to engage Hitler except as a social companion. Although we have heard his rants and ravings about the Jews, the Russians, his own treacherous generals and his paranoid delusions, Braun is actually able to confide to Junge, toward the end: “He only talks about dogs and vegetarian meals. He doesn’t want anyone to see deep inside of him.” Seeing inside of him is no trick at all: He is flayed bare by his own rage.

“Downfall” premiered at Toronto 2004, and was one of this year’s Oscar nominees for best foreign film. It has inspired much debate about the nature of the Hitler it presents. Is it a mistake to see him, after all, not as a monster standing outside the human race, but as just another human being?

David Denby, The New Yorker: “Considered as biography, the achievement (if that’s the right word) of ‘Downfall’ is to insist that the monster was not invariably monstrous — that he was kind to his cook and his young female secretaries, loved his German shepherd, Blondi, and was surrounded by loyal subordinates. We get the point: Hitler was not a supernatural being; he was common clay raised to power by the desire of his followers. But is this observation a sufficient response to what Hitler actually did?”

Stanley Kauffman, The New Republic: “Ever since World War II, it has been clear that a fiction film could deal with the finish of Hitler and his group in one of two ways: either as ravening beasts finally getting the fate they deserved or as consecrated idealists who believed in what they had done and were willing to pay with their lives for their actions. The historical evidence of the behavior in the bunker supports the latter view. … ‘Downfall,’ apparently faithful to the facts, evokes — torments us with — a discomfiting species of sympathy or admiration.”

Admiration I did not feel. Sympathy I felt in the sense that I would feel it for a rabid dog, while accepting that it must be destroyed. I do not feel the film provides “a sufficient response to what Hitler actually did,” because I feel no film can, and no response would be sufficient. All we can learn from a film like this is that millions of people can be led, and millions more killed, by madness leashed to racism and the barbaric instincts of tribalism.

What I also felt, however, was the reality of the Nazi sickness, which has been distanced and diluted by so many movies with so many Nazi villains that it has become more like a plot device than a reality. As we regard this broken and pathetic Hitler, we realize that he did not alone create the Third Reich, but was the focus for a spontaneous uprising by many of the German people, fueled by racism, xenophobia, grandiosity and fear. He was skilled in the ways he exploited that feeling, and surrounded himself by gifted strategists and propagandists, but he was not a great man, simply one armed by fate to unleash unimaginable evil. It is useful to reflect that racism, xenophobia, grandiosity and fear are still with us, and the defeat of one of their manifestations does not inoculate us against others.