“The life you lead, the freedom you have–will you deny my daughters the same chance?” Not the request every mother would address to a prostitute, but “Dangerous Beauty” makes a persuasive case for the life of a courtesan in 16th century Venice. At a time when Europeans are bemused by our naivete about dalliance in high places, this is, I suppose, the film we should study. It’s based on the true story of Veronica Franco, a well-born Venetian beauty who deliberately chose the life of a courtesan because it seemed a better choice than poverty, or an arranged marriage to a decayed nobleman.

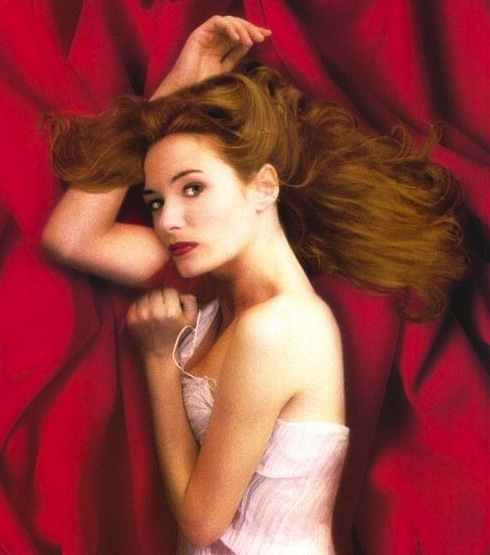

Veronica, played by Catherine McCormack with cool insight into the ways of men, is a woman who becomes the lover of many because she cannot be the lover of one. She is in love with the curly headed Marco (Rufus Sewell), and he with her, but they cannot wed; “I must marry,” he tells her, “according to my station and my family’s will.” Veronica knows this is true, and knows, too, that because her father has squandered the family fortune, she is also expected to marry money.

Shall they then become unmarried lovers? Marco persuasively argues, “God made sin that we might know his mercy.” But then Veronica, her virginity lost, could never make a good marriage. Her mother (Jacqueline Bisset) has a better idea. “You cannot marry Marco, but you shall have him! You’ll become a courtesan–like your mother used to be.” Veronica’s eyes widen, but her mother’s logic prevails, and the daughter is launched on a training course in grooming, fashion and deportment. Her mother even shows her to a great Venetian library, off limits to women, but not to Veronica (“Courtesans are the most educated women in the world”). For a courtesan, as for an army recruit, the goal is to be all that she can be. And indeed Veronica is soon the most popular and respected fallen woman in Venice, sought by princes, generals and merchants, and even dandled on the knee of the cardinal.

The film, directed with great zest by Marshall Herskovitz, positions this story somewhere between a romance novel and a biopic. It looks like Merchant-Ivory but plays like “Dynasty.” And it’s set in a breathtakingly lovely Venice, where special effects have been used to empty the Grand Canal of motorboats and fill it with regattas and gondolas. No city is more sensuous, more suited to intrigue, more saturated with secrets.

McCormack plays Veronica as a woman not averse to physical pleasure (the morning after her initiation, she smiles dreamily and asks, “Who’s next?”). But sex is not really the point with a courtesan. She provides intellectual companionship for her powerful clients; through her connections, she can share valuable pillow talk. And there is high entertainment as she uses poetry for verbal duels with noblemen. Her lover Marco, by contrast, is doomed to marriage with a rich girl who, like all wives of the time, is sheltered and illiterate. “Do you like poetry?” he asks her hopefully on their wedding night. “I know the psalms,” she replies.

Obviously a woman with so much power must be a witch. In a courtroom scene that I somehow doubt played out quite this way in real life, she defends herself and the life of a courtesan. It is better, she argues, to prostitute herself willingly, for her own gain, than to do so unwillingly in an arranged marriage: “No biblical hell could be worse than a state of perpetual in-consequence.” I am not surprised, as I said, that the screenwriter is a woman. Few movies have been so deliberately told from a woman’s point of view. We are informed in all those best-sellers about Mars and Venus, that a man looks for beauty and a woman for security. But a man also looks for autonomy, power, independence and authority, and a woman in 16th century Venice (and even today) is expected to surrender those attributes to her husband. The woman regains her power through an understanding of the male libido: A man in a state of lust is to all intents and purposes hypnotized. Most movies are made by males and show women enthralled by men. This movie knows better.