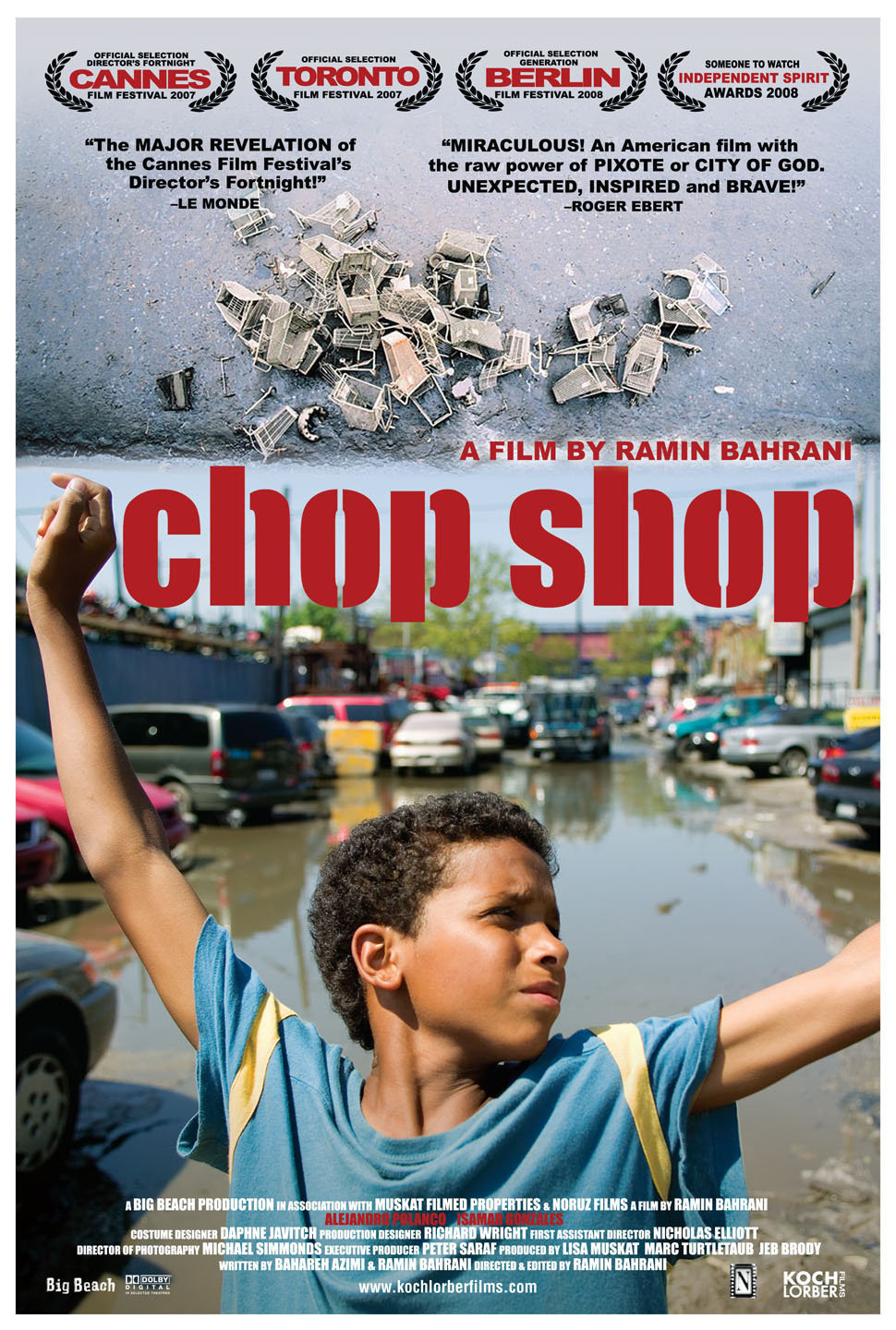

“Chop Shop” has such an immediate sense of time and space that it comes as a slight shock to understand that the time is now and the place is in the shadow of the late Shea Stadium — or, more accurately, next to the right-field parking lot. This area is known as the Iron Triangle, a crowded, ramshackle bazaar of auto-parts shops. We see it through the eyes of Alejandro, universally known as Ale, a 12-year-old who lives and works there. If you squint a little to turn the automobiles into carriages, this would be a story by Dickens.

Ale is enterprising and optimistic. In exchange for his work, he lives in a knocked-together plywood room under the roof of a shop owned by a man named Rob. He gets $5 for every passing car he flags onto the premises. This income he supplements by selling candy on the subway, peddling bootlegged DVDs, stealing hubcaps and snatching purses. He is not a criminal. He is a survivor. He goes at things as he has taught himself, and will make the record in his own way: first to knock, first admitted, sometimes an innocent knock, sometimes not so innocent.

That is how Saul Bellow wrote of Augie March. “Chop Shop” (2007) also evokes F. Scott Fitzgerald, who wrote about this very area in The Great Gatsby. He named it the Valley of the Ashes. In the 1920s, it was the wasteland on the way from East and West Egg to Manhattan: Occasionally, a line of gray cars crawls along an invisible track, gives out a ghastly creak and comes to rest, and immediately the ash-gray men swarm up with leaden spades and stir up an impenetrable cloud, which screens their obscure operations from your sight.

Ale is in the tradition of American symbols of upward striving. A Latino, he is in the line of those poor Jews, Irish and Italians who landed in New York and hustled for a living. He is an immensely strong boy, and a vulnerable kid. He seems to be an orphan, but he has a sister, Isamar, four years older, and he visibly glows when she comes to live with him. He has been preparing this home for them. When she complains it is small, he is cheerful: It has a little refrigerator. It has a microwave. She will be happy.

Bahrani immersed himself in the Iron Triangle while writing his screenplay. Only one of his actors had ever worked in a movie before; Ahmad Razvi, who plays a shady operator, had been in one, Bahrani’s own “Man Push Cart” (2005). Ale’s boss, Rob Sowulski, owns and operates the shop where Ale lives. Everyone you see works in the Iron Triangle, except for Ale (Alejandro Polanco) and Isamar (Isamar Gonzales), who are schoolkids. What is remarkable is the way, after careful preparation and multiple takes, Bahrani finds performances in them that are so natural and convincing, they put professional actors to shame.

He depends on preparation and his visual sense, collaborating always with the same meticulous cinematographer, Michael Simmonds. This month, I joined Bahrani in a shot-by-shot analysis of the film at the University of Colorado at Boulder. It was an illuminating experience. I knew that it was a great film, a universal film and how well it worked. Bahrani knew why it worked, and was brave enough to discuss his methods, which directors are often reluctant to do.

The screenplay was revised over and again, removing all unnecessary digressions and obvious Look at Me moments. The three-act structure was so deeply embedded in the events, they seemed to flow inevitably. Specific turning points were used in important scenes; sometimes they were no more than a subtle change in tone, but they were emotionally decisive. Much was made of Antonioni painting some grass for “Blow Up,” because it was not green enough. Bahrani and Simmonds composed every shot with acute attention to detail. Often foreground elements forced characters toward the left, more problematic, side of the screen. No auto junk in the background was there by chance. In the lighting of faces, they took Bergman’s Sven Nykvist as their ideal. There is a pickup truck that has a small sticker of a soccer ball on its back gate. Bahrani and Simmonds discussed whether it should be there: “Was it contributing, or distracting?”

Although there was rehearsal, he said, he avoided drilling his actors. He told them what to say, and they tended to slip into their own word choices. Ale and Isamar discuss a pair of brand-name sneakers. The screenplay used the word “real.” Isamar used the word “official,” the correct street word. Some shots were captured unobserved; the movie used no clapboard to begin and end shots, and Bahrani and Simmonds could communicate with a nod or a gesture. The high-def camera was always around, and Simmonds was always peering through it to set up shots; sometimes the actors were unaware they were being filmed. Bahrani also likes long shots with the camera far enough back so it is not evident. As Ale grabs a purse (from a cast member) on a walkway leading to the parking lot, nobody else in the shot knows they are in a movie.

“Chop Shop” is about a hard coming of age. Ale’s dream is that he and his sister will buy a taco truck and go into business on their own. He saves every dollar. She won’t have to work in Ahmad’s truck anymore. In a heartbreaking scene, Ale glimpses how she has started to augment her income. He never directly confronts her. He works harder to make money, to buy her things, to make money less necessary to her. He is a brother, but also in a sense, a husband. He wants to take responsibility. He learns some inescapable realities about the limitations of his power and undergoes a shift into tacitly understanding why she earns as she does. He will be 13 soon, and then 23, and one day we are sure he will own a taco truck, but not now, and certainly not the shabby truck he has set his dreams on. Reality is taking him on the first steps toward the American Dream, and they are lower steps than we like to remember.

Ramin Bahrani was born in 1975 in Winston-Salem, N.C., and is not, as has been misreported by many, including me, an immigrant from Iran. His parents came from Iran. His father is a psychiatrist in Winston-Salem, practicing much among poor blacks and whites. Bahrani says neither he nor his family has experienced racism there, although at school, there were “whites, blacks, and my brother and me.” His parents have instilled a love of Persian poetry. Once during a conversation, he mentioned the poems of Hafez of Shiraz (1315-1390), which are used as an oracle like the I Ching by many Persians. I asked if I could present a question to Hafez. He told me not to speak it aloud. He telephoned his father in North Carolina, who opened his volume at random and took 15 minutes to translate what he found there. It was relevant.

It may be this dual heritage that inspires Bahrani to look more closely at the many new Americans among us. “Man Push Cart” was about the Pakistani operator of a Manhattan sidewalk bagel cart. Such carts are part of the daily routines of many New Yorkers, who may rarely look at those behind the counter. His 2008 film, “Goodbye Solo,” is about a Senegalese-American taxi driver in Winston-Salem, and an old man who hires him for a trip that worries him. The taxi driver is played by Souleymane Sy Savane, from the Ivory Coast. The old man is played by Red West, who met Elvis Presley in high school and was his longtime bodyguard. Only in America.

“Chop Shop” and “Man Push Cart” have both been selections at Ebertfest.