This is strange. I have no interest in running and am not a partisan in the British class system. Then why should I have been so deeply moved by “Chariots of Fire,” a British film that has running and class as its subjects? I’ve toyed with that question since I first saw this remarkable film in May 1981 at the Cannes Film Festival, and I believe the answer is rather simple: Like many great films, “Chariots of Fire” takes its nominal subjects as occasions for much larger statements about human nature.

This is a movie that has a great many running scenes. It is also a movie about British class distinctions in the years after World War I, years in which the establishment was trying to piece itself back together after the carnage in France. It is about two outsiders, a Scot who is the son of missionaries in China, and a Jew whose father is an immigrant from Lithuania. And it is about how both of them use running as a means of asserting their dignity. But it is about more than them, and a lot of this film’s greatness is hard to put into words. “Chariots of Fire” creates deep feelings among many members of its audiences, and it does that not so much with its story or even its characters as with particular moments that are very sharply seen and heard.

Seen, in photography that pays grave attention to the precise look of a human face during stress, pain, defeat, victory, and joy. Heard, in one of the most remarkable sound tracks of any film in a long time, with music by the Greek composer Vangelis Papathanassiou. His compositions for “Chariots of Fire” are as evocative, and as suited to the material, as the different but also perfectly matched scores of such films as “The Third Man” and “Zorba the Greek.” The music establishes the tone for the movie, which is one of nostalgia for a time when two young and naturally gifted British athletes ran fast enough to bring home medals from the 1924 Paris Olympics.

The nostalgia is an important aspect of the film, which opens with a 1979 memorial service for one of the men, Harold Abrahams, and then flashes back sixty years to his first day at Cambridge University. We are soon introduced to the film’s other central character, the Scotsman Eric Liddell. The film’s underlying point of view is a poignant one: These men were once young and fast and strong, and they won glory on the sports field, but now they are dead and we see them as figures from long ago.

The film is unabashedly and patriotically British in its regard for these two characters, but it also contains sharp jabs at the British class system, which made the Jewish Abrahams feel like an outsider who could sometimes feel the lack of sincerity in a handshake, and placed the Protestant Liddell in the position of having to explain to the peeved Prince of Wales why he could not, in conscience, run on the Sabbath. Both men are essentially proving themselves, their worth, their beliefs, on the track. But “Chariots of Fire” takes an unexpected approach to many of its running scenes. It does not, until near the film’s end, stage them as contests to wring cheers from the audience. Instead, it sees them as efforts, as endeavors by individual runners — it tries to capture the exhilaration of running as a celebration of the spirit.

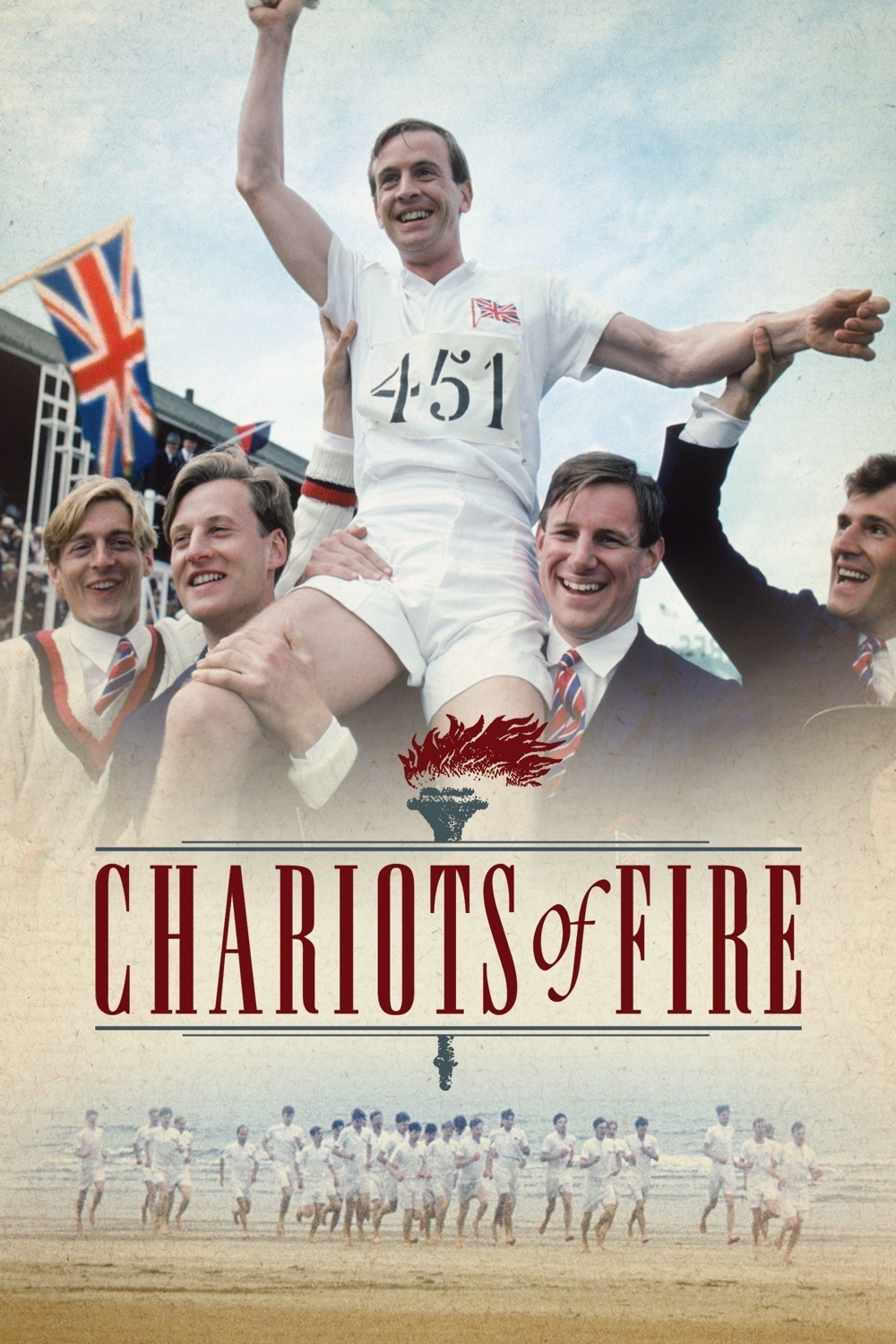

Two of the best moments in the movie: A moment in which Liddell defeats Abrahams, who agonizingly replays the defeat over and over in his memory. And a moment in which Abrahams’ old Italian-Arabic track coach, banned from the Olympic stadium, learns who won his man’s race. First he bangs his fist through his straw boater, then he sits on his bed and whispers, “My son!” All of the contributions to the film are distinguished. Neither Ben Cross, as Abrahams, nor Ian Charleson, as Liddell, are accomplished runners but they are accomplished actors, and they act the running scenes convincingly. Ian Holm, as Abrahams’ coach, quietly dominates every scene he is in. There are perfectly observed cameos by John Gielgud and Lindsay Anderson, as masters of Cambridge colleges, and by David Yelland, as a foppish, foolish young Prince of Wales. These parts and others make up a greater whole.

“Chariots of Fire” is one of the best films of recent years, a memory of a time when men still believed you could win a race if only you wanted to badly enough.