The American college fraternity experience has birthed a growing subgenre of films, with Richard Linklater’s “Everybody Wants Some!” and Andrew Neel’s “Goat” sparking recent discussion for the way they use Greek organizations’ obsession with male bonding rituals and tradition as a way to criticize the world beyond college. The tale of an “Everyman” college student being drafted into a fraternity as a pledge and sticking with it through Hell Week and beyond is inherently dramatic, and not just because it comes with a handy built-in time frame, one semester or year of higher education. Almost every pledge story told on film seems to end up becoming the story of innocence lost or ignorance reinforced. The young man seeking fraternity initiation goes into the experience in search of abstract ideas like “brotherhood” and “oneness,” and emerges on the other side cynical and disillusioned or radicalized and awake. The journey can be played at any emotional pitch, and because the main characters are young men living in the zone between adolescence and true adulthood, the filmmaker can play it all sorts of ways, from slapstick comedy (“Old School“) to horror (“The Brotherhood”)

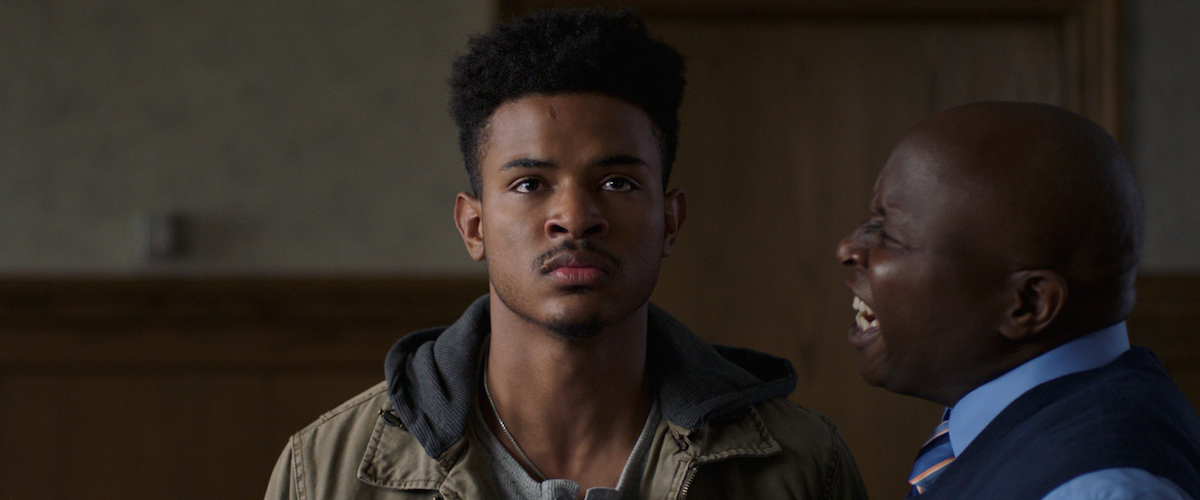

“Burning Sands,” Gerald McMurray’s feature filmmaking debut, is one of the fresher entries, thanks mainly to its setting: a historically black fraternity on a historically black campus like Howard, the university where the co-writer and director got his degree. Spike Lee’s second feature “School Daze” had a subplot set in a black frat and showcased a lot of hazing, but the scenes were played mainly for very grim laughs. “Sands” presents itself in trailers as a comedy along those lines, but it’s no joke. McMurray’s strongest virtue is his ability to thread that comedy-drama needle while he tells the story of Zurich (Trevor Jackson), aka Z, into Lambda Phi, a prestigious Greek organization once attended by the school’s dean (Steve Harris), who proposes the young man for membership.

Co-written with Christine Berg, “Burning Sands” often makes the first-time filmmaker’s error of trying to say everything that can possibly be said about its chosen subject in two hours and trying to fold the rather slim story into two many generic shapes at the same time, as if the director were afraid that he was never going to make another movie if he failed, so he better make five or six movies while he’s at it. Thus the story of Z’s transformation is treated as a standard-issue Young Man Grows up story but also as a boot camp movie about dehumanization, a borderline docudrama about the contradictions of Greek life on an African-American university campus, a satire about adults acting like adolescents and adolescents play-acting adulthood, and most of all, a look at how organizations swathed in idealism and the nostalgic glow of tradition tend to reproduce ideology and brainwash their members into repeating the same old codes from one generation to the next.

The latter gives “Burning Sands” most of its sting, though. There’s a double-edged quality to seeing a black college that has been the site of cultural and intellectual emancipation taking such unseemly pride in subjecting pledges to rituals that are imbued with situations drawn straight from the slave past that African-Americans have struggled to escape. The basic, rather crude justification for doing this sort of thing often amounts to, “This is what I went through, so you’re going through it, too—and you need to shut up and take it like a man.” No real evolution is possible if practices can’t be refined or eliminated in the name of progress, though.

This conundrum gives “Burning Sands” some of its sharpest scenes. Z is eager to be a part of something larger to himself, and eager to belong most of all; but the organization that would have him as a member is filling his brain with toxic garbage about manhood, and some of it sounds uncomfortably like the codes passed down from slaveowners to slaves back in the day. McMurray has already drawn some flack for interweaving the story of Z’s fraternity experience with miniaturized history lessons (taught by Alfre Woodard’s professor) about the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who gave this fictional college its name. But considering what a metaphor-rich environment we’re seeing onscreen, it seems churlish to fault the director for turning subtext into text and putting things in boldface. McMurray is one of the producers of Ryan Coogler’s brilliant “Fruitvale Station,” a film that had a lot to say about how black American masculinity is constantly at risk of re-enacting the same abusive structures it is theoretically trying to rebel against.

The pledges are dehumanized, renamed, stripped of their old history and treated as empty vessels into which the history of the brotherhood can be poured. Hazing is illegal in theory, but it’s still very much a reality for a lot of college students. McMurray doesn’t stint on the slapstick weirdness, military movie brutality and borderline horror-film torture that the experience entails. Taking it literally underground—as many fraternities do by hazing pledges in basements where authorities cannot see or hear what’s happening—wraps a shameful practice in a handy-dandy metaphorical bow.

As is often the case in sports films and movies about basic training, there are so many characters onscreen at the same time that it’s hard for the film to delineate them, but a few stand out: Nafessa Williams as nonchalantly sexual townie; DeRon Horton as a well off pledge, nicknamed Square; and Trevante Rhodes (“Moonlight”) as a frat member who seems too sensitive to be a part of an organization like this. The film makes some of its points skillfully and others rather clumsily, but there’s so much going on in it, both intellectual and in terms of moment-to-moment action, that it’s never boring, and you definitely come away from the experience with very mixed feelings about what you’ve seen and how it was presented, which feels just about right for a story like this one.