Now streaming on:

“Urban Light,” an art installation on the grounds of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, by the Wilshire Boulevard entrance, is, I think it’s safe to say, one of the most popular pieces of public art in the United States. The elegantly arranged sculptural array of over 200 old-style street lamps, which via solar power snap on at dusk and go out after dawn, has been featured in more than several feature films, on the covers of Los Angeles tourism brochures, in television commercials for California, and so on. Not bad for a work that is not yet even ten years old. It is, among other things, a remarkably friendly and accessible piece of public art; unlike Richard Serra’s controversial 1981 “Tilted Arc,” a curved raised scar across the plaza of New York’s Federal Plaza; a challenge in the form of an artwork that was answered by its 1985 removal from the space. The irony of “Urban Light” and its magical reputation is that it is the work of an artist who had at one time been one of the most controversial, and vitriol-inspiring, of the late 20th century: Chris Burden, the subject of this consistently fascinating documentary.

The movie begins with one of Burden’s most memorable statements. A television commercial he made in the early ‘70s, and paid to place on various stations, reeling off a list of great artists’ names: Leonardo, Michelangelo, Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Picasso, and ending with his own name. “I was gonna use Warhol too but he was still alive and I didn’t want to give him a free commercial,” Burden says to an interviewer from that era, a dark haired loudly-dressed man who it took me a little while to recognize as Regis Philbin, who did indeed have an L.A. chat show on television in the ‘70s. Then there’s newer footage of Burden leading the film crew around the grounds of his seemingly airplane-hangar sized studio near Topanga Canyon. He speaks of his habit of hiking around the grounds; it takes a whole two hours to circle it, he says. In his mid-sixties at the time of shooting, he seems both calm and robust. Through narration, interviews, and some really amazing archival footage—crudely shot stuff documenting his exploits in conceptual and performance arts—filmmakers Richard Dewey and Timothy Marrinan cram a lot of incident and ideas into Burden’s life story.

The young Burden spoke with an eerie calm that you could see as rather seductive, and he sure needed that quality, many of his contemporaries confirm, in order to pull off some of his schemes. He grew up the son of an engineer who consulted at MIT, and like his dad, he had big ideas as he studied to be an architect—so big he wasn’t willing to wait through an apprenticeship to realize them. He turned to art instead, and took a determinedly conceptual road, living in a padlocked locker for five days as his first piece. “We weren’t sure if he was dangerous or crazy,” one of his school friends remembers.

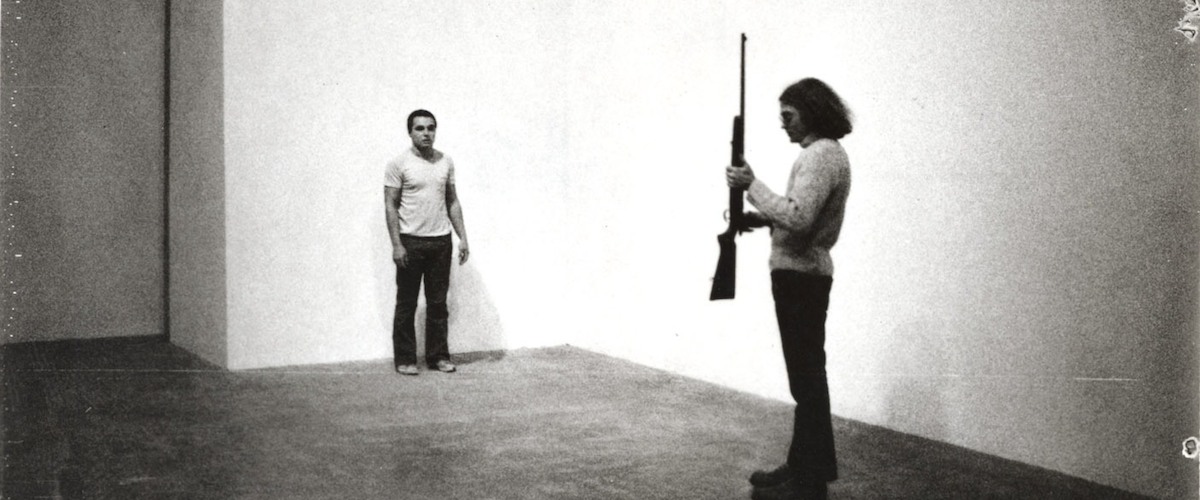

Around this time the British art critic Brian Sewell turns up to bemoan the lack of “craft” in such work and insist that it’s not at all. Burden, giving an account of his thinking, discusses the dimensionality of sculpture, the active nature of apprehending it (“you’re supposed to walk around”) and on concluding that “sculpture is action” lays the groundwork for his increasingly outrageous pieces, the most well-known of which have the artist actually getting shot with a rifle (the details of this performance are more terrifying than that description even directly implies) or having himself semi-crucified on the back of a Volkswagen Beetle whose engine is revved to maximum for two minutes while he lies there. (The object, Burden says, was to explode the car. What then? The work also inspired the David Bowie couplet “Tell you who you are/if you nail me to my car.”) “I keep wanting not to say the word ‘sado-masochistic,’” the critic Peter Schjeldal says, settling on “sinister” to describe both Burden and his work at the time. Even the less famous pieces, such as one in which he laid behind a pane of glass at the Chicago Art Institute … for several days. One critical skeptic who became a kind of believer in Burden’s artistic legitimacy was our own Roger Ebert, who at first was among those who considered Burden an Evel Knievel of art but admitted that once he saw Burden’s Chicago piece it stuck with him, making him “ponder the nature of time itself.”

The movie goes on to chronicle Burden moving away from performance and starting to build actual things, after a period when sustained drug abuse and strained personal relations were indeed causing him to act in dangerous ways on an extracurricular basis. His early works involving craft were not initially benign. When you hear him say, “I was thinking about flywheels a lot,” you say, “uh oh.” Artist Ed Ruscha describes his terror at being in the same room with the contraption.

Jonathan Gold, the legendary L.A. food critic who was once an assistant to Burden, observes of the late work, “The idea that he’d become loved and emblematic of Los Angeles in that cuddly way—no one would have thought of that.” One thing I found missing from this movie was more explanatory material—the hows and whys of Burden changing his process. Certainly a piece such as “Urban Light” fits into his views about sculpture and activity. I can put that together. But I wanted to hear more anyway. Burden died in 2015, at age 69, of a cancer he had battled for a while. The story of how he unveiled his last piece is a testimony to his passion and commitment. He was a real artist and, especially if you believe that art is all about asking questions, about life and about art, he was a great one.

Glenn Kenny was the chief film critic of Premiere magazine for almost half of its existence. He has written for a host of other publications and resides in Brooklyn. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here.

88 minutes